Running Head: Corticosteroid Dose in Exacerbations of COPD

Funding Support: Not applicable.

Date of acceptance: November 2, 2015

Abbreviations: acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, AECOPD; Cochran Central Register of Controlled Trials, CENTRAL; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; Grading, Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation, GRADE; forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FEV1; forced vital capacity, FVC; arterial oxygen tension, PaO2; oxyhemoglobin saturation, SpO2; oral, PO; intravenous, IV; every, q; every day, qD

Citation: Arcos DB, Krishnan JA, William KR, et al. High-dose versus low-dose systemic steroids in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2016; 3(2): 580-588. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.3.2.2015.0178

Introduction

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) are characterized by increased cough, sputum production, and dyspnea. They impair quality of life, frequently require urgent care or hospitalization, and increase the cost of care.1 Systemic steroids are a mainstay of AECOPD treatment. They reduce treatment failure, shorten hospital length of stay, improve lung function, and reduce dyspnea; however, they also cause hyperglycemia, delirium, fluid retention, and other side effects.2 The balance of these desirable and undesirable effects probably varies according to the steroid dose.

Observational studies suggest that low-doses of systemic steroids may be superior to high-doses in patients with AECOPD,2-4 even though high doses are more commonly used.5 In the most recent study, Kiser et al performed a retrospective cohort study that compared low-dose systemic steroids (defined as the equivalent of methylprednisolone ≤240 mg/day) with high-dose systemic steroids (defined as the equivalent of methylprednisolone >240 mg/day) in 17,239 patients with an AECOPD. Participants who received low-doses of steroids had a shorter hospital stay, intensive care unit stay, duration of mechanical ventilation, and less frequent hyperglycemia requiring insulin and fungal infections.2 Lindenauer et al and Vondracek et al similarly performed retrospective cohort studies that favored low-dose systemic steroid therapy.3,4 While this observational evidence is suggestive, such studies are susceptible to bias due to unmeasured confounders. Therefore, randomized trials are necessary to confirm that the effects seen in the observational studies are, in fact, due to the intervention rather than confounders.

We performed a systematic review to search for randomized trials that addressed our question, “Should patients having an AECOPD receive low-dose or high-dose systemic steroids?” The goal of the systematic review was to confirm that the optimal dose of systemic steroids in patients having a COPD exacerbation is a knowledge gap, as background for a future proposal to conduct a randomized controlled trial comparing high-dose systemic steroids with low-dose systemic steroids in this population.

Methods

Literature Search

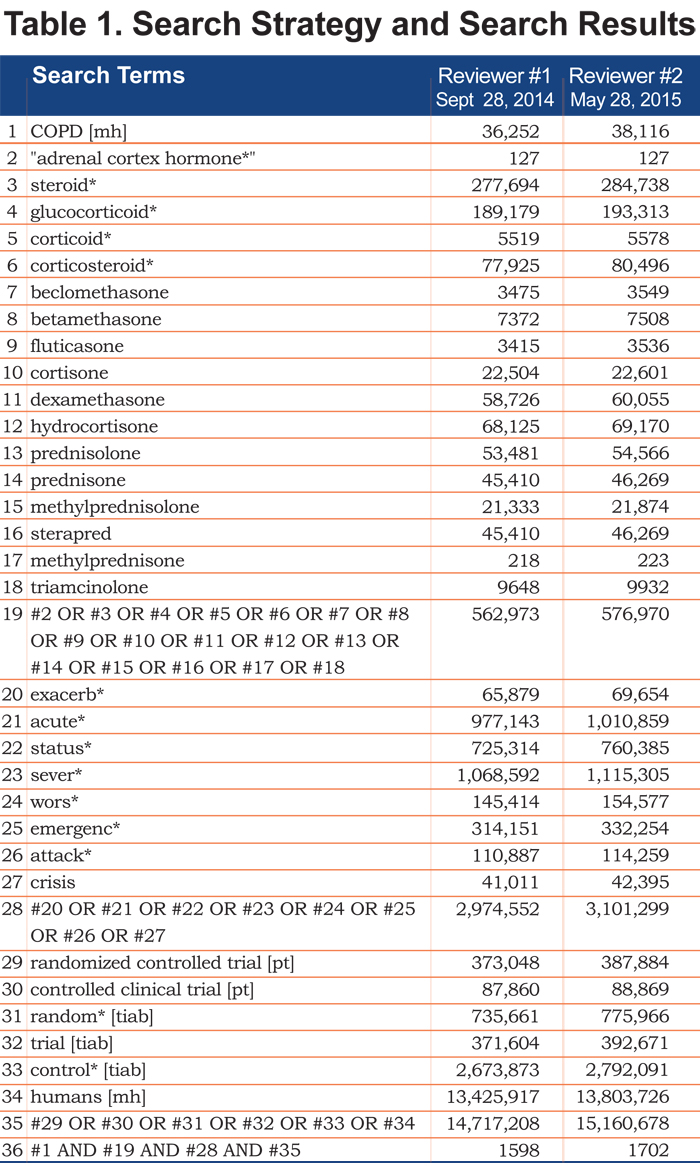

Two researchers (DBA, KCW) independently searched the MEDLINE database using the PubMed search engine and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) database. The sensitive search strategy was built around the medical subject heading, “COPD [mh]”, and variations of keywords for exacerbation (i.e., exacerb*, acute*, status*, sever*, wors*, emergenc*, attack*, and crisis), steroids (i.e., “adrenal cortex hormone”, steroid*, glucocorticoid*, corticoid*, corticosteroid*, beclomethasone, betamethasone, fluticasone, cortisone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone, prednisone, methylprednisolone, sterapred, methylprednisone, and triamcinolone), and randomized controlled trials (i.e., randomized controlled trial, controlled clinical trial, random*, trial, and control*). The search was restricted to human studies, but there were were no restrictions on language, dates searched, or publication status.

Study Selection

Study selection criteria included the following: randomized trial, enrolled patients having an AECOPD, compared one systemic steroid regimen to another, measured clinical outcomes, and published in a peer-reviewed journal. The decision to include trials that compared one systemic steroid regimen to another, rather than including only trials that compared one dose to another, was made to ensure that subgroup analyses comparing one dose to another would not be missed.

The researchers (DBA, KCW) independently screened the titles and abstracts, and then full text articles. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus. Another researcher (WC) was designated as the final arbiter of disagreements that could not be resolved by discussion, but this was not necessary.

Evidence Synthesis

The research plan stipulated that data comparing one systemic steroid dose with another would be extracted from the selected studies and recorded on a data extraction sheet by one researcher (DBA) and then verified by another researcher (KCW). Two analyses were planned for each clinical outcome. The first was to categorize the systemic steroids as low-dose or high-dose and compare the effects on each clinical outcome; the second, if feasible, was to look for a dose-response gradient by determining the effect of each systemic steroid dose on each outcome. The quality of evidence was then to be appraised using the Grading, Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.6 However, no randomized trials comparing one systemic steroid dose with another were identified and, therefore, the research plan was modified to a qualitative summary of the evidence comparing various systemic steroid regimens.

Results

The sensitive literature search of the MEDLINE database identified 1598 articles during an initial search done by KCW in the fall of 2014 and 1702 articles during a repeat search by DBA in the summer of 2015 (Table 1).

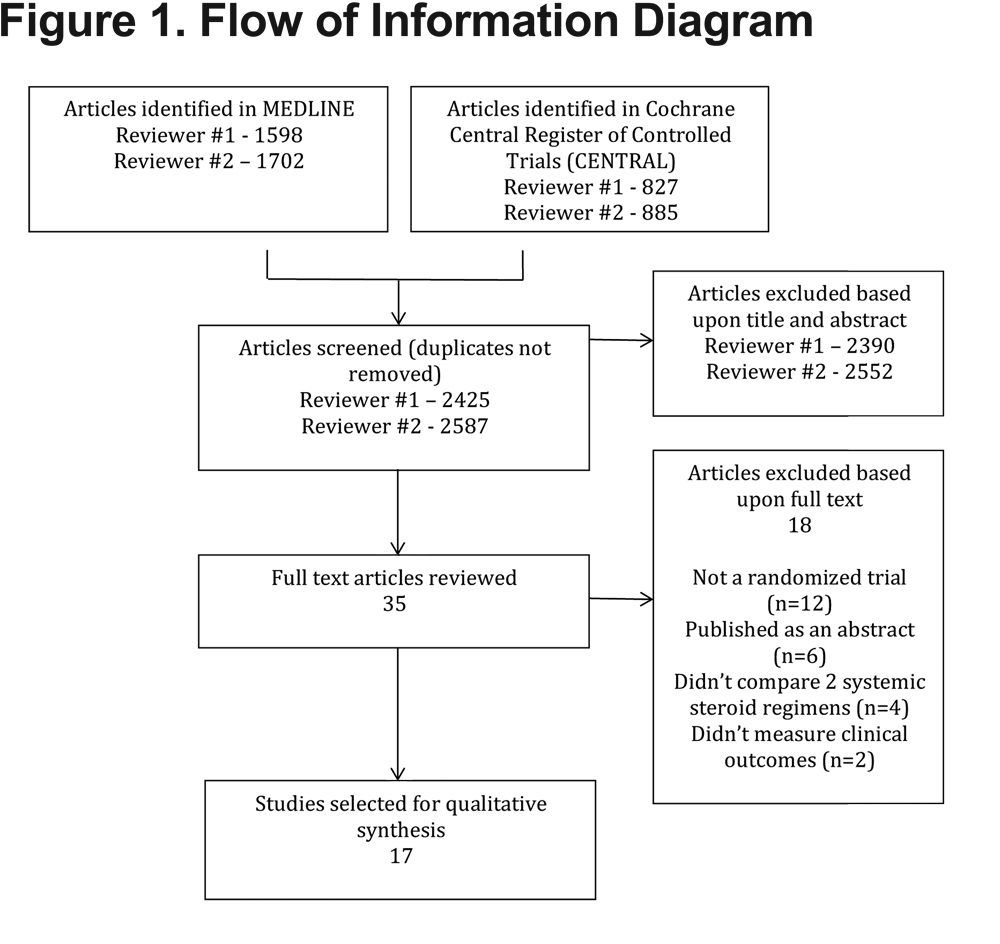

A similar search of the CENTRAL database identified 827 articles during an initial search done by KCW in the fall of 2014 and 885 articles during a repeat search by DBA in the summer of 2015. The vast majority of articles were excluded by review of the title and abstract, leaving 35 articles for full text review. Among the articles that underwent full text review, 24 were excluded and 11 were selected. Reasons for exclusion included the article not being a randomized trial (e.g., a journal club; n=12), the study being reported as an abstract but never published in a peer-reviewed journal (n=6), the control group being something other than an alternative systemic steroid regimen (i.e., placebo or a non-steroid agent; n=4), and measurement of physiological rather than clinical outcomes (n=2) (Figure 1).

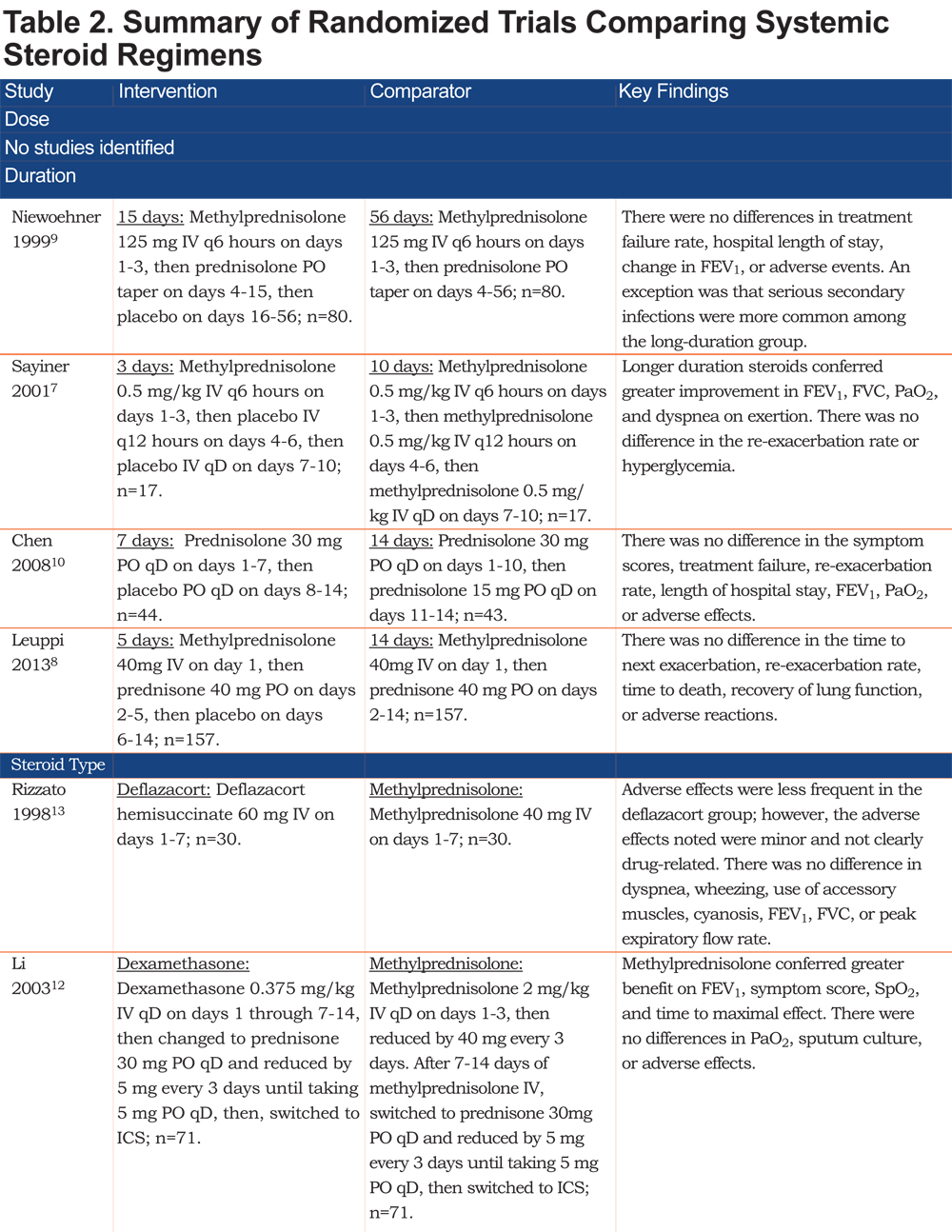

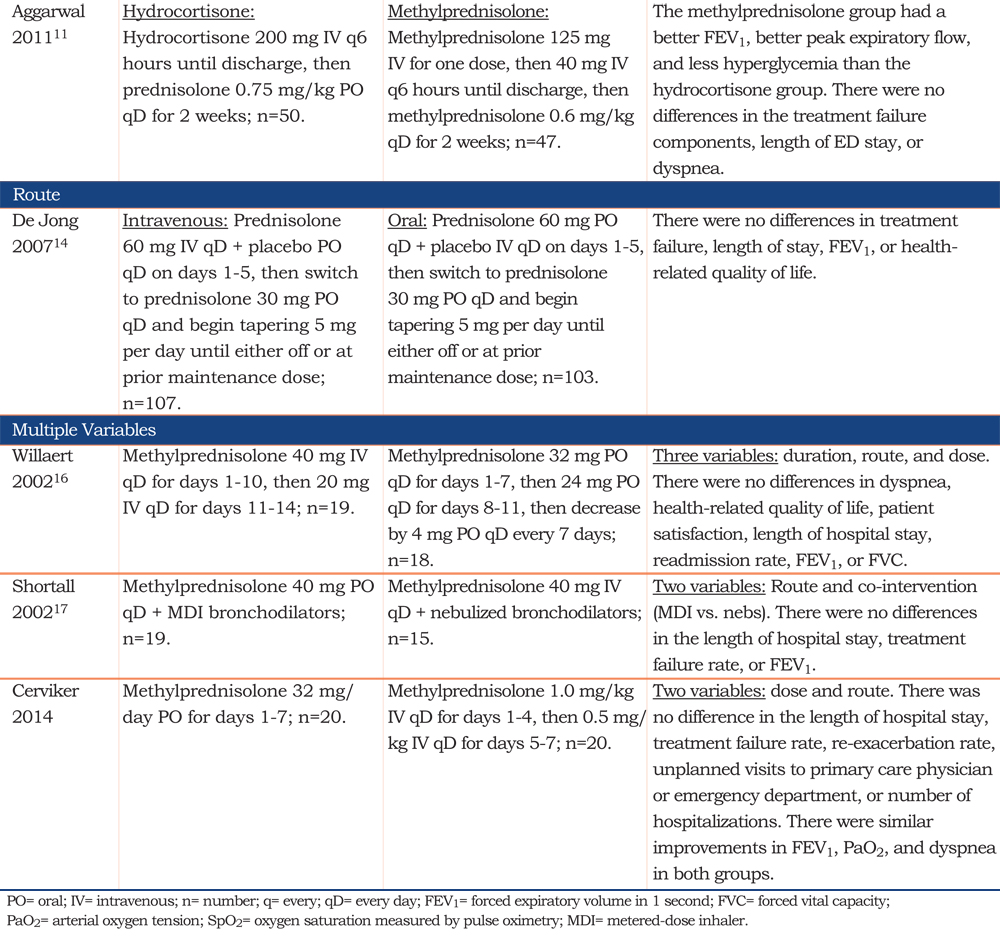

We did not identify any randomized trials that compared the effects of different systemic steroid doses on clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD, either as a primary comparison or a subgroup analysis. The selected trials comparing one systemic steroid regimen with another in patients with AECOPD included 4 randomized trials that compared durations of systemic steroid treatment, 3 randomized trials that compared types of systemic steroids, 1 randomized trial that compared different routes of steroid delivery, and 3 randomized trials that compared multiple variables (Table 2).

Duration of Steroid Treatment

Four randomized trials compared different durations of systemic steroid treatment.7-10 The trials compared 3 days with 10 days,7 5 days with 14 days,8 15 days with 56 days,9 and 7 days with 14 days.10 Three trials (n= 561 patients) found no difference in the re-exacerbation rate, treatment failure rate, hospital length of stay, dyspnea, frequency of adverse events, or physiological measures (i.e., forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], forced vital capacity [FVC], arterial oxygen tension [PaO2]).8-10 In contrast, 1 trial (n=34 patients) found no difference in the re-exacerbation rate or incidence of hyperglycemia, but reported that a longer duration of systemic steroids conferred greater improvement in the FEV1, FVC, PaO2, and dyspnea on exertion.7

Type of Steroids

Three trials randomly assigned patients with an AECOPD to methylprednisolone or an equivalent dose of hydrocortisone (n=97 patients),11 dexamethasone (n=142 patients),12 or a novel systemic steroid, deflazacort hemisuccinate (n=60 patients).13 Compared with methylprednisolone: patients who received hydrocortisone had no difference in the treatment failure rate, length of stay in the emergency department, or dyspnea, but had a lower FEV1, lower peak expiratory flow rate, and more hyperglycemia11 ; patients who received dexamethasone had no differences in PaO2, sputum culture, or adverse effects, but had less improvement in their FEV1, symptom score, and SpO2, as well as a longer duration to maximal effect 12; and, patients who received deflazacort had similar FEV1 and peak expiratory flow measurements.13

Route of Steroid Delivery

One trial randomly assigned 210 patients with AECOPD to receive intravenous or oral prednisolone at equivalent doses and durations.14 There were no differences in the treatment failure rate, length of hospital stay, FEV1, or health-related quality of life.

Multiple Variables

Three randomized trials compared multiple variables.15-17 Two of the trials included the dose as one of the variables 15,16; however, neither performed a subgroup analysis to compare the doses.

One randomized trial varied both the dose and route, randomly assigning 40 patients with AECOPD to receive methylprednisolone 32 mg per day orally for 7 days or 1 mg/kg per day intravenously for 4 days and then 0.5 mg/kg per day orally for 3 days.15 The groups had a similar length of hospital stay, treatment failure rate, re-exacerbation rate, rate of unplanned visits to the primary care physician or emergency department, and hospitalization rate. There were also similar improvements in the FEV1, PaO2, and dyspnea in both groups. More patients in the low-dose arm developed respiratory failure and died, but there were too few events to determine if the difference was real. There was a trend toward less hyperglycemia and less hypertension with the low dose regimen.

Another randomized trial varied the duration, route, and dose. The trial randomly assigned 37 patients with AECOPD to receive either methylprednisolone 40 mg per day intravenously for 10 days and then 20 mg per day intravenously for 4 days, or alternatively a tapering dose of methylprednisolone orally for 46 days.16 There were no differences in dyspnea, health-related quality of life, patient satisfaction, length of hospital stay, readmission rate, FEV1, or FVC.

The third randomized trial varied the route of administration and co-interventions. Thirty-four patients with AECOPD were randomly assigned to receive methylprednisolone 40 mg orally plus bronchodilators by meter dose inhaler or, alternatively, methylprednisolone 40 mg intravenously plus nebulized bronchodilators.17 No differences were detected in the length of hospital stay, treatment failure rate, or FEV1.

Discussion

Systemic steroids administered to patients with AECOPD reduce treatment failure, shorten hospital length of stay, improve lung function, and reduce dyspnea.2 However, observational evidence suggests that high-dose systemic steroids (i.e., the usual clinical practice5) are associated with worse clinical outcomes than low-dose systemic steroids.2-4 A potential explanation for this observation is that the undesirable effects of systemic steroids are probably more common or more severe when higher doses are used, including hyperglycemia, delirium, fluid retention, muscle weakness, infection, and other side effects.

Observational evidence may be misleading because results may be influenced by unmeasured confounders. Therefore, we sought randomized trials to answer our question, “Should patients having an AECOPD receive low-dose or high-dose systemic steroids?” Despite reviewing the titles, abstracts, and/or full text of roughly 2000 articles, we did not identify a single randomized trial that compared high-dose systemic steroids with low-dose systemic steroids in patients with AECOPD, or that provided enough data for us to perform our own analysis. Therefore, a critical knowledge gap exists and randomized trials comparing high-dose with low-dose systemic steroids in patients with AECOPD are urgently needed.

While we did not find any trials evaluating the dosing of systemic steroids, we did identify multiple trials that compared different durations, types, and routes of systemic steroid therapy, as well as trials comparing multiple variables. Overall, it appeared that short durations of systemic steroids were as effective as longer durations on most clinical outcomes.7-10 There was no evidence that alternative steroid types were superior to methylprednisolone11-13 and oral steroids appeared as effective as intravenous steroids.14

The major limitation of our study is the high rate at which new studies related to the treatment of AECOPD are being published, as indicated by the observation that more than 100 potentially relevant articles were published between our first literature search in the fall of 2014 and our repeat literature in the summer of 2015. Thus, it is possible, that a relevant study will be published between the completion of our literature search in the summer of 2015 and publication of this systematic review. In addition, neither foreign language databases nor allied health databases were searched; therefore, the possibility that a relevant study was not detected cannot be excluded. Finally, we did not reach out to the authors of the trials that varied multiple variables, including dose, to obtain the raw data and perform our own subgroup analysis comparing doses.

Conclusion

Our systematic review failed to identify any randomized trials comparing different doses of systemic corticosteroids for patients with AECOPD. Observational studies suggest higher doses are associated with the potential for adverse effects, but such analyses do not provide strong evidence due to the potential for unmeasured confounding or bias. Randomized controlled trials that measure patient-centered outcomes are needed to support the choice of systemic steroid dose in patients with AECOPD.

Declaration of Interest

DBA and KCW have an interest in evidence synthesis.JAK is a member of the COPD Foundation’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee, is on the Advisory Board of the COPD Foundation’s PRAXIS (Prevent and Reduce COPD Admissions through eXpertise and Innovation Sharing) initiative, and is the principle investigator of multiple COPD-related studies funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. RWV is Director of the University of Colorado’s COPD Center and has published both a large observational study and a review article on the same topic as this manuscript. JES was a founding member of the United States Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group and participates in critical care-related clinical trials. WC has research interests in epidemiology, COPD, and critical care. THK is a clinical pharmacist with an interest in dosing optimization in the intensive care unit. He has published both a large observational study and a review article on the same topic as this manuscript. JWW is President and Co-founder of the COPD Foundation .JLS is Director of Public Policy and Advocacy for the COPD Foundation. RAW is Chair of the COPD Foundation’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee. He has participated as a clinical center principle investigator, steering committee member, coordinating center investigator, or chair for many of the major COPD clinical trials or cohorts over the past 20 years.