Running Head: A Patient-Centered Walking Program

Funding Support: This study (116703) was funded by a grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

Date of Acceptance: July 14, 2016

Abbreviations: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; modified Medical Research Council, mMRC; forced expiratory in 1 second, FEV1; pulmonary rehabilitation, PR; forced vital capacity, FVC; National Health & Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES; Global initiative for Chronic Lung Disease, GOLD; COPD Assessment Test, CAT; St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, SGRQ; intent-to-treat, ITT; analysis of covariance, ANCOVA; body mass index, BMI; confidence interval, CI; long-acting muscarinic, LAMA; inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting beta2-agonist, ICS/LABA

Citation: Bender BG, Depew A, Emmett A, et al. A patient-centered walking program for COPD. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2016; 3(4): 769-777. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.3.4.2016.0142

Introduction

*Note: Results contained in this manuscript were presented at the 2015 American Thoracic Society International Conference in Denver.

Decreased activity often accompanies the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in turn accelerating health decline1,2 and death.3,4 Substantial evidence indicates that a sustained activity program reduces these risks by increasing endurance, muscle strength, and quality of life5-7 while decreasing exacerbations.8,9 Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a cornerstone in the management of COPD to improve exercise capacity. However, patients’ access to pulmonary rehabilitation is often limited by a number of barriers: (1) In many locations, PR is not available; (2) Providers do not prescribe PR for their COPD patients;10 (3) Even where PR referrals were made, 60% of patients in one study either did not attend or began attending PR sessions and then stopped;11 (4) The positive effects of 7 weeks12 or 25 weeks13 of PR were lost when patients did not translate their experience into ongoing physical activity after PR was completed. The reasons patients discontinue exercise following participation in a PR program have been reported to include lack of intrinsic motivation, preference for sedentary lifestyle, weather, or other health problems.14,15 Home PR programs have been established in an attempt to overcome some of these barriers. However, a review of 18 trials including 733 randomized COPD patients concluded that while home-based rehabilitation resulted in an increase in exercise capacity, no improvement occurred in maximal workload, hospital admissions, or mortality.16

Walking, a relatively simple home exercise program, has proven beneficial to COPD patients. Patients who walked at least 60 minutes per day reduced their COPD re-hospitalization rate by 50 percent17 and walking at least 5000 steps/day is a target objective to avoid many of the detriments of physical inactivity in COPD patients.18 A simple activity monitor, typically a pedometer, can facilitate increased walking in COPD patients.19 However, many patients remain unmotivated, concerned about shortness of breath, or lacking the confidence to start a daily walking program.15 Motivating COPD patients through an individualized program with frequent personal contacts, goal setting, and case management designed to increase behavior change can be effective but may require significant resources at high cost. The need exists, therefore, for a simple, effective, low-resource individualized home walking program requiring limited, strategic professional intervention. The purpose of this study was to test a home-based walking program for COPD patients that included a single visit and goal setting followed by 5 brief telephone calls.

Methods

Study Design

This was a single-center, randomized, 3-month study. Patients meeting eligibility criteria made 3 study visits. At visit 1, patients signed a consent form, underwent spirometry testing, and completed 3 self-report questionnaires. The initial visit was followed by a 7-10 day run-in during which patients wore an Omron pedometer to establish baseline steps/day. At the second visit, patients were randomized to the intervention or control condition and instructed to continue to wear the pedometer for the 12-week study intervention period during which they received a telephone call every 2 weeks for 10 weeks. All patients recorded their daily steps from their pedometer onto a study calendar and reported these in the telephone calls with their wellness coach. A third visit occurred 2 weeks after the fifth call at which patients returned their pedometer and completed an exit interview with a staff member who was not their wellness coach. This study was approved by the National Jewish Health Institutional Review Board (protocol number HS2748).

Participants

Participants were enrolled from patients attending pulmonary outpatient clinics at National Jewish Health, Denver, Colorado. Patients qualified for participation if they were at least 40 years of age and had a smoking history of at least 10 pack years, an established COPD diagnosis, were prescribed one or more maintenance medications, and had a pre-bronchodilator spirometry with FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of <0.70 and a pre-bronchodilator FEV1 of ≥ 30 and ≤ 80% of predicted normal values using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) reference equations. Exclusion criteria were other significant disease, ≥ 3 COPD exacerbations in the previous year (defined as an acute worsening of symptoms of COPD requiring new or increased doses of systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, and/or emergency treatment or hospitalization), or any hospitalization within 12 weeks prior to visit 1.

Study Arms

Goal Setting: The in person and telephone interventions were conducted by a wellness coach, a licensed professional counselor who routinely works with COPD patients. Patients in the Goal arm met with the wellness coach for 30 minutes at visit 2 to discuss and set a personally selected goal involving increasing time spent in an individually important activity such as being able to go shopping or spend time with a grandchild. Adopting a motivational interviewing strategy, the wellness coach assisted the participant in establishing for themselves a personally meaningful goal. The wellness coach explained how increasing walking would assist the participant in reaching their personal goal. The coach also established a target of increasing steps/day by approximately 15% per month, although this target was adjusted depending upon each patient’s goal progress. In each of the 20-minute, bi-weekly telephone calls, the wellness coach discussed the participant’s perception of progress toward reaching their personal and their steps/day goals and barriers to accomplishing the goals. If necessary, the wellness coach assisted the participant in modifying the walking goal or, if the goal had been reached, establishing a new goal. The objective in these calls was to be positive, supportive, and encouraging in working towards the personal activity goals. The online data supplement contains additional information about the wellness coaching protocol.

Control: Patients in the control arm wore the pedometer and recorded steps on the study calendar. Bi-weekly telephone calls were limited to communicating their steps/day with the study staff. While they were encouraged to walk, they were not instructed to set personal activity goals or discuss barriers to increased walking. Study staff answered questions and provided information, but did not offer additional support.

Questionnaires: The research protocol employed 3 questionnaires recommended in the 2014 Global initiative for chronic Lung Disease standards to measure dyspnea, general symptoms, and quality of life at baseline and following the 12-week study period.20

- The British modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale contains 5 statements that patients rate on a scale of 0-4 reflecting minimal (e.g., “I only get breathless with strenuous exertion”) to severe symptoms (e.g., “I am too breathless to leave the house”).21

- The COPD Assessment Test (CAT) contains 8 items reflecting severity of cough, sputum, dyspnea, chest tightness, capacity for exercise and activities, confidence, sleep quality and energy levels.22

- The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) is a 40-item quality of life measure of the impact of COPD on overall health, daily life, and well-being.23

Data Analyses

The targeted sample size was 100 randomized participants completing the study. Two populations were defined for this study: Intent-to-Treat (ITT) population and the Completer population. The ITT population included all participants who had been randomized into the study. The ITT population was the primary analysis population for summaries of demographic/background and secondary endpoint data. The Completer population included all participants in the ITT population who completed the 12-week intervention period; this population served as the primary analysis population for the primary endpoint.

The primary endpoint, mean percent change from baseline in steps/day at Week 12 (based on a weekly [7-day] mean calculated for each participant), was compared between the 2 intervention groups using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with intervention group, baseline severity (post-bronchodilator FEV1 % predicted), smoking status and baseline mean steps as terms in the model. While pre-bronchodilator FEV1 was employed in the inclusion criteria, only post-bronchodilator FEV1 was used in the ANCOVA model. As this was a pilot study, the study was not powered to statistically detect differences in any measure between the Goal group and the Control group. Statistical testing was interpreted descriptively and statistical programming was performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Version 9.3. For the secondary endpoints, the change from baseline values in SGRQ-C score, CAT score, mMRC dyspnea score and body mass index (BMI) at Week 12 were also compared between intervention groups using ANCOVA models. Subgroups of interest were determined prospectively for comparison of the primary endpoint, steps/day, between the Goal group and the Control group. Subgroups included those based on more or less disease severity defined as patients with a baseline mMRC dyspnea score of 2 or more versus a score of 1 or less, as well as patients with a baseline post-bronchodilator FEV1 % predicted value below 60% versus a value ≥60%. This cut point was adjusted to 50% predicted in post-hoc analysis.

Results

Baseline

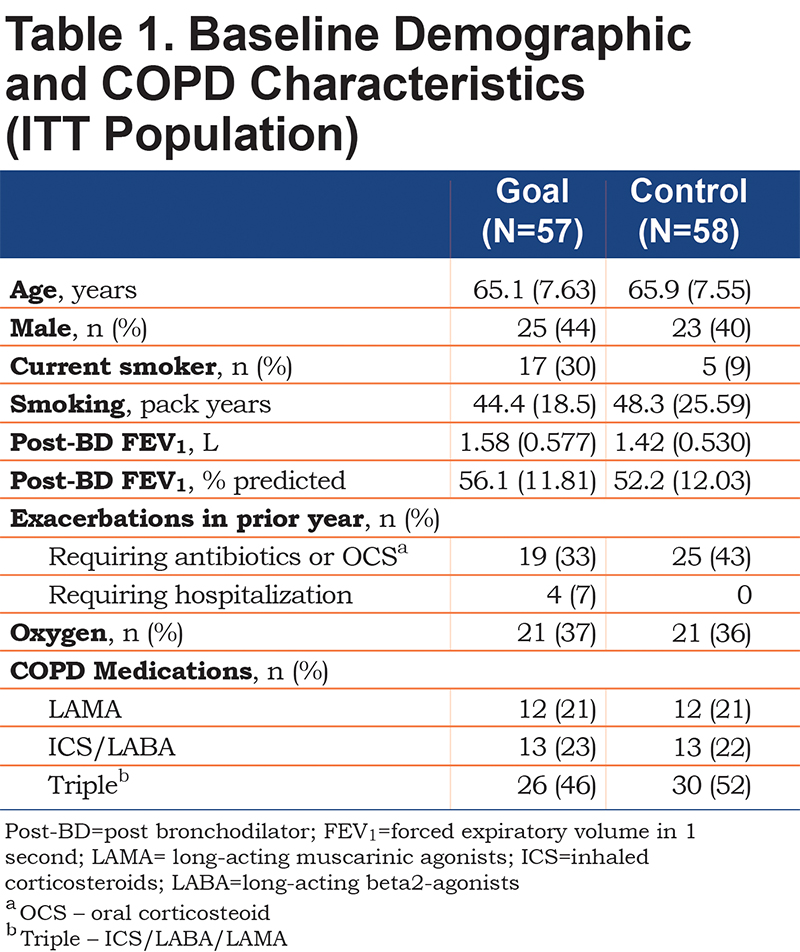

At baseline, demographic and disease-related characteristics of the Goal and Control groups were similar and reflective of significant disease (Table 1). Half were being treated with a combination of long-acting muscarinic antagonist, long-acting beta2-agonist, and inhaled corticosteroid and over a third was receiving supplemental oxygen, possibly reflective of the Denver elevation. Forty-nine of 57 patients in the Goal group and 50 of the 58 in the Control group completed the study and provided a Week 12 mean steps/day assessment forming the Completer population.

Primary Outcome

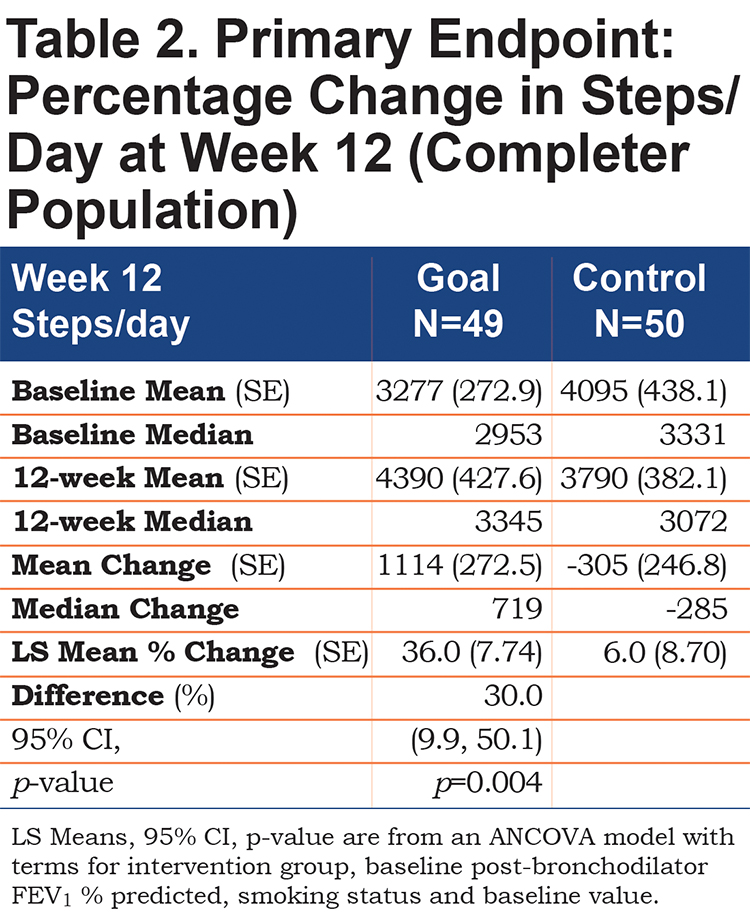

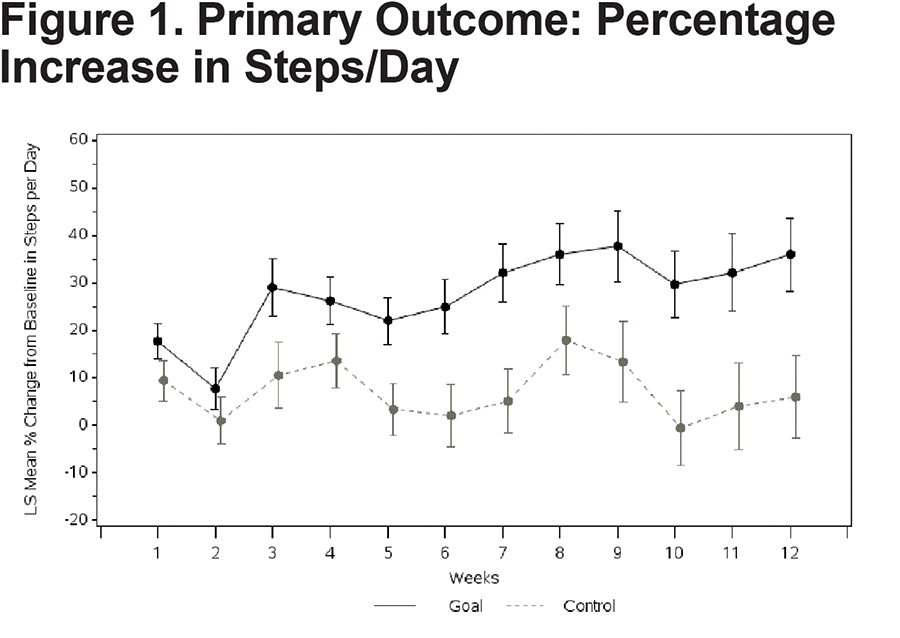

Patients in the Goal group had a significantly larger mean percent increase in average steps/day over 12 weeks (36.0 ± 7.74) compared with patients in the Control group (6.0 ± 8.70) with a mean difference of 30% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 9.9, 50.1), (p=0.004)(Table 2). The increase persisted over time (Figure 1) and averaged 4390 (range: 860 to 15,793) steps/day in the Goal group, contrasted with 3790 (range: 763 to 14,167) steps/day in the Control group at Week 12.

Secondary Outcomes

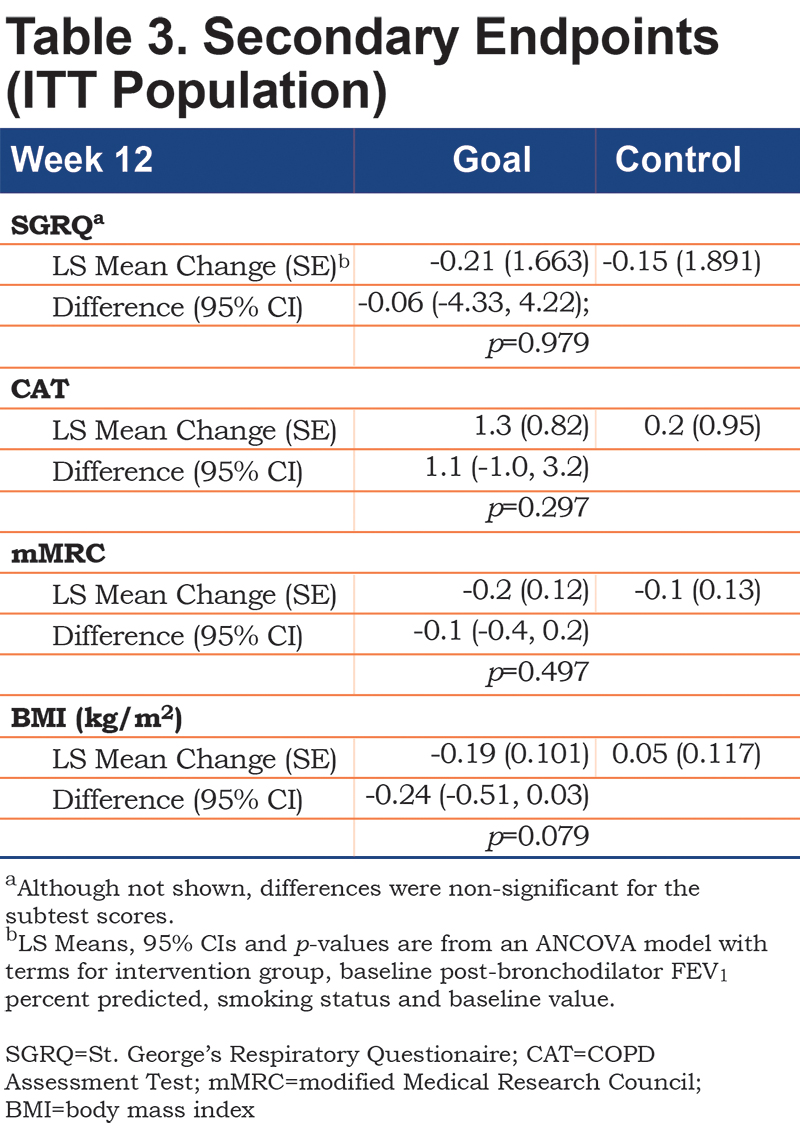

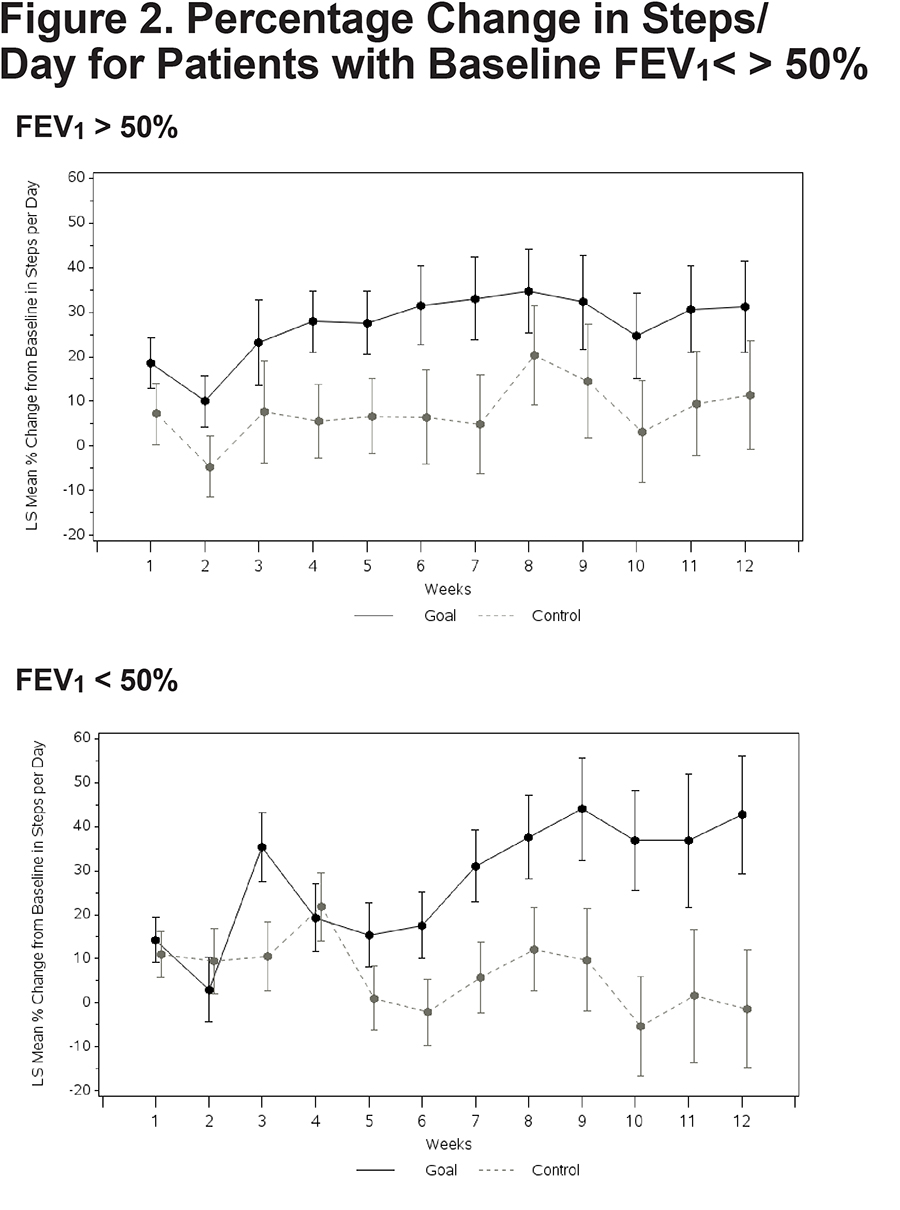

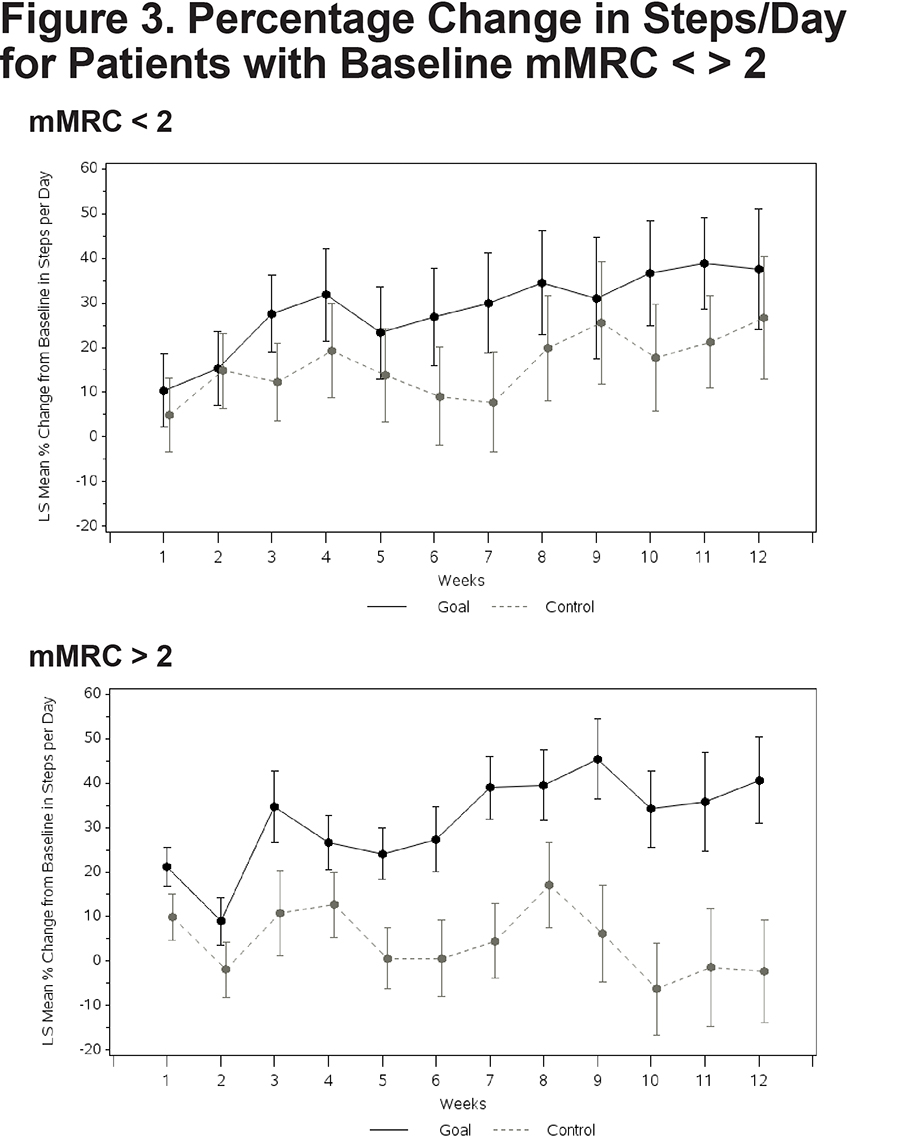

No significant between-group differences emerged on any of the composite or subtest scores from the 3 self-report questionnaires (Table 3). A nonsignificant trend emerged suggesting a reduced BMI in the Goal group over 12 weeks. Both patients with higher versus lower disease severity demonstrated an increase in walking. Goal patients with FEV1 % predicted below 50% walked more (Goal [N=18] = 42.7% increase in steps [13.35], Control [N=21] = -1.4 [13.35], Difference=44.2; 95% CI 7.7, 80.6; p value=0.019) (Figure 2). Goal participants with an mMRC dyspnea score of 2 or more demonstrated a significant increase in steps/day relative to Control patients (Goal [N=33] = 40.7% increase [9.72]; Control ([N=28] = -2.3% [11.62]; Difference 43.0; 95% CI 15.1, 70.9; p=0.003) (Figure 3). The cost of the intervention, including wellness coaching and pedometer, was $146 per Goal patient.

Personal Goal Achievement

Patients in the Goal group selected their own personalized goals. Hence, individual goals varied considerably between participants with few identical goals. However, overall the selected goals fell into one of 5 categories: (1) increased energy and stamina; (2) reduced shortness of breath; (3) increase in a specific activity (e.g., house projects, time with grandchildren, shopping); (4) weight loss; and (5) increased sense of well-being. A total of 48 out of 49 patients partially or fully achieved at least 1 goal; 9 of these did so after revising their original goal. A total of 15 patients achieved their initial goal and then set a second goal. For example, 1 patient established an initial goal to start swimming, followed later by a second goal to begin using a stationary bicycle. Another patient set a goal of walking more outside and later a second goal of engaging in activities with a grandchild. Many expressed satisfaction at their success with statements that included “I’m getting stronger and breathing better”, “I pushed myself harder than I normally would have”, “It's nice to have someone to hold me accountable” and “The more I get out and do it (walking), the more I feel like I can”.

Discussion

A relatively low-resource wellness coaching, goal setting intervention modestly improved the activity level of COPD patients over a 12-week period. Patients who participated in the intervention demonstrated a 6-fold greater percent increase in walking compared to the control group. Patients who achieved their goal walked more than those who did not, and those who set more than one goal walked even more. All patients entered the study on appropriate maintenance therapy, hence increased walking was not the result of initiation of new medication. Notably, even patients with greater pulmonary impairment, including those with baseline FEV1 below 50% or an mMRC dyspnea score of 2 or more, demonstrated a significant increase in daily walking. Hence, a relatively simple walking program may benefit a large population of patients with mild to severe COPD and may be adopted as one component of a comprehensive COPD management plan. The $146-per-patient cost of the intervention contrasts with hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation that can exceed $2000.24 Despite the fact that increased walking improves survival, no significant changes in quality of life scores accompanied the increase in steps, possibly because the study interval was insufficient to establish the benefits of increased walking.

Qualitatively, wellness coaching was well received. However, success of the intervention also depended upon skilled wellness coaching during brief, telephone-based sessions. The initial goal setting was not always successful when patients tended toward setting goals that were too nonspecific (e.g., feeling better) or ambitious (e.g., walking for 60 minutes). Consequently, goal setting often required reconsideration and modification. A few patients became discouraged, concerned about physical ailments, or inhibited by challenging weather as barriers to motivation or opportunity to increase their walking. Still others were surprised at their success and subsequently wanted to set a second or even a third goal.

Other investigators have also established the benefits from basic clinic- or home-based training programs; results from these studies were mixed and few assessed the cost of their intervention. Aggregate data from 18 trials of home-based rehabilitation for COPD patients indicated that exercise capacity improved but maximal workload, hospital admissions, and mortality did not.16 A review of 8 trials utilizing low cost equipment and 3 utilizing strength training found significant improvements in exercise capacity and quality of life.25 Several studies with some methodological limitations provide preliminary evidence suggesting that innovative home-based exercise programs offer potential benefit including 2 non-randomized studies of COPD patients demonstrating improved physical capacity following pedometer-based feedback26 or mobile phone support.27 Another innovative intervention included a web-based home exercise program and active telephone coaching, but adherence dropped to 21% over the course of the program and no evidence supported a change in physical stamina.28 Patients describe motivation-depleting barriers that include the perception of being too busy, travel required to participate, comorbidities, lack of social support, or simply low motivation to commit.29 Another study recruited veterans with COPD and invited them to participate in an online program; the half randomized to the intervention had more pedometer-recorded steps and an improvement in 2 quality of life domains at 4 months.30 In the present study, regular telephone contact after an initial face-to-face visit appears to have provided necessary support for goal selection and activity improvement. However, it remains unclear which elements of a home-based exercise program, and in particular the amount and type of human coaching, determine success. Future innovative studies may combine wellness coaching with online or mobile telephone-based interventions, comparing the relative benefits of different components.

Limitations to the present study must be noted. While Goal patients demonstrated increased walking that was sustained over 12 weeks, the intervention should be tested for sustained walking over longer time periods, providing more opportunity to assess impact on health and quality of life. Within a longer study protocol, assessment of sustainability and key clinical outcomes including objective measures of physical function such as the 6-minute walk test, systemic inflammation, body mass index, hemoglobin A1c, COPD symptoms, exacerbations, health care utilization, and mortality are possible and will be informative of the overall potential benefit to patients with COPD. While cost-per-patient was established in this study, a formal cost-benefit analysis was not conducted but will be possible and necessary in a long-term study of a low-cost, home-based walking program for COPD patients.

Conclusion

A simple and low-cost home walking program increased steps/day in COPD patients, including those with significant respiratory impairment. Key to the success of the intervention appears to be the patient-centered approach that included development of a relationship with the wellness coach who tailored the intervention around the patient’s personal goals. A larger, longer study is required to better establish the overall health impact, sustainability, and cost-benefit of the intervention. Further investigation may be directed at understanding the optimal blend of personal coaching, remote support including mobile communication technology, and time and resource investment to identify the “sweet spot” of low-cost, personalized coaching to produce significant benefits to patients.

Acknowledgments

The investigators express their thanks to Kendra Hughes and Ibrahim Raphiou for their assistance with the data analyses.

Declaration of Interest

DS is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline and holds stock/shares in GlaxoSmithKline. AE, now an employee of PAREXEL International, was an employee of GlaxoSmithKline at the time the study was conducted and holds stock/shares in GlaxoSmithKline. SS was an employee of GlaxoSmithKline at the time the study was conducted and holds stock /shares in GlaxoSmithKline. All other authors have confirmed that they have no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.