Running Head: Images in COPD

Funding Support: Not applicable

Abbreviations: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency AATD; human immunodeficiency virus, HIV; hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome, HUVS; alpha-1-antitrypsin protein, AAT; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ESR; forced expiratory volume per 1 second, FEV1; forced vital capacity, FVC; total lung capacity, TLC; residual volume, RV

Citation: Leung SS, Lee P, Most JE, Sundaram B. Images in COPD: idiopathic emphysema in a never smoker. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2020; 7(2): 130-133. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.7.2.2020.0148

Introduction

Smoking is an important risk factor for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This risk includes exposure to secondhand smoking. However, it is estimated that 10% of patients with emphysema have either rarely or never smoked.1 In this population, depending on the clinical picture, further consideration should be given to other potential causes for emphysema such as idiopathic, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), heritable connective tissue disorders, intravenous drug abuse, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS), and environmental exposures.

Case History

“G.S” a 73-year-old male with no history of smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke presented for evaluation of increasing limitation of physical activity with shortness of breath. At this time, he was diagnosed with asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. He was medically managed with inhaled corticosteroids and a long-acting beta2- agonist. He denied a history of intravenous drug abuse. Blood work revealed an alpha-1-antitrypsin protein (AAT) level of 141 mg/dL (normal 101 – 187 mg/dL). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 2 mm/hr (normal 0 – 30 mm/hr). C1q complement levels were 15.0 mg/dL (normal 11.8 – 23.8 mg/dL).

Imaging

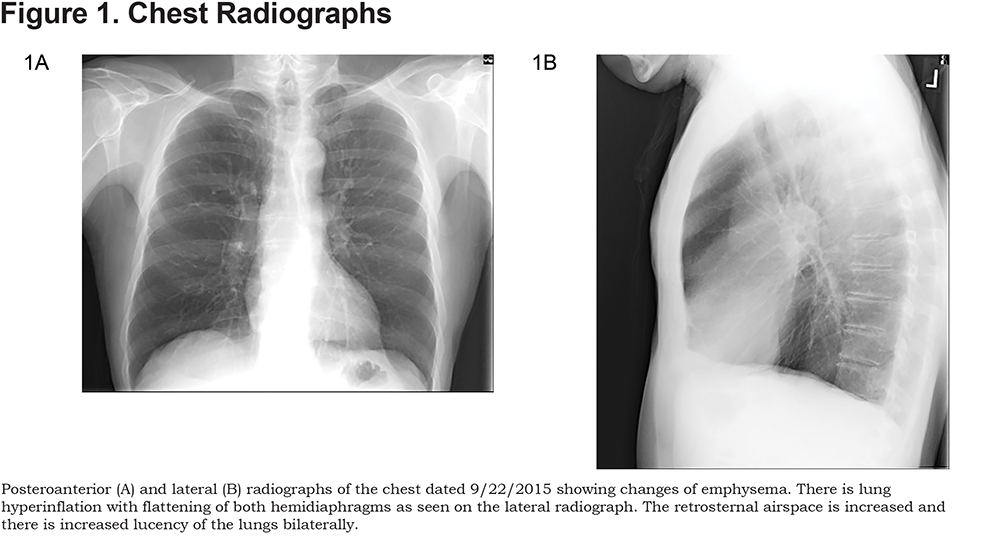

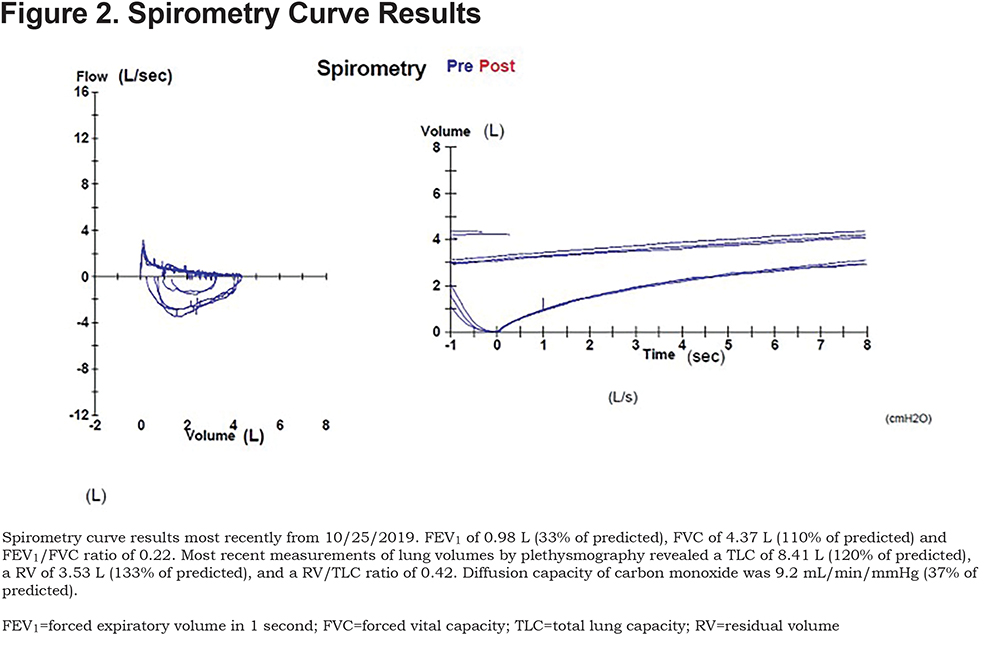

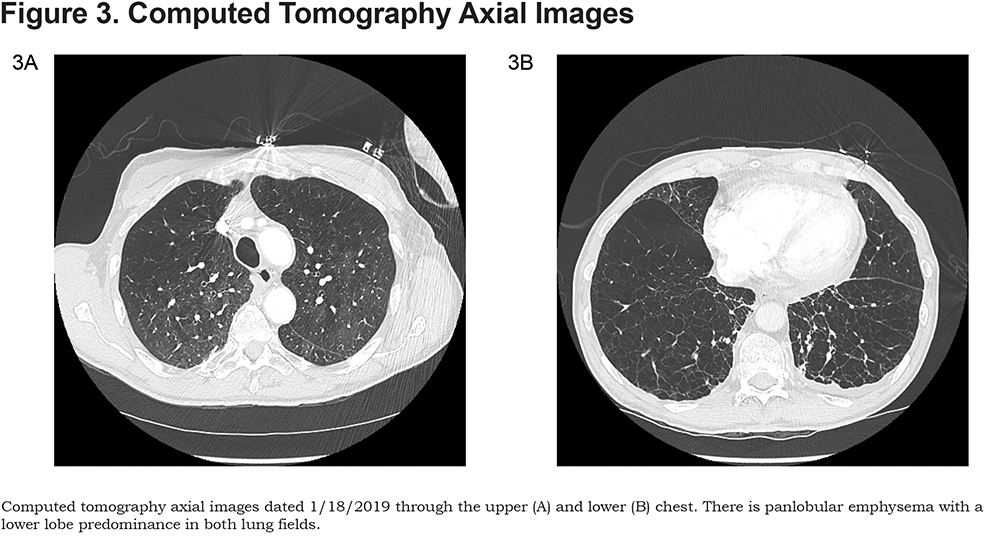

Here are the images taken of patient G.S., along with spirometry results. (Figures 1, 2, and 3).

Discussion

This clinical presentation highlights a case of severe emphysema in a nonsmoker. While smoking remains the de facto risk factor for the development of emphysema, in a never smoker patient, other potential etiologies should be considered.

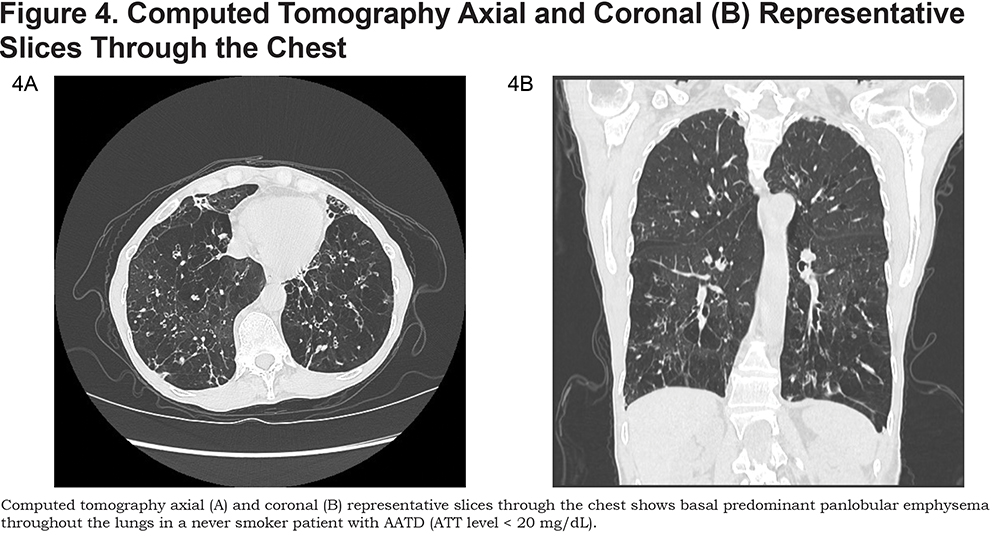

It is estimated that AAT accounts for approximately 3% of cases of emphysema.2 The rate of decreased lung function is strongly affected by cigarette smoking in AAT patients. Radiological evidence of emphysema is more prevalent in smokers (approximately 90%) than non-smokers (approximately 65%).3 AAT should be suspected if the patient presents with emphysema at a young age (< 45 years old), the emphysema is in a non-smoker, the emphysema is in a radiographical basilar predominant pattern, there is adult onset asthma or there is a family history of lung and liver disease (Figure 4).4 Diagnosis is confirmed with a serum AAT level < 57 mg/dL along with genetic confirmation.

Heritable connective tissue disorders are a heterogenous group of diseases which include Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Cutis Laxa. Structural changes from gene mutations which affect tissue elasticity may predispose to the development of emphysema. 5-7

Intravenous drug use has been associated with early onset development of emphysema. Talc, or hydrated magnesium silicate, is used in oral tablets such as methylphenidate and phenmetrazine to hold the components of the medication together. Injected talc can migrate to the lungs causing a granulomatous foreign-body reaction, which can continue to tissue destruction leading to apical bullous emphysematous changes.8

The relationship between HIV status and emphysema was first described in the 1980s. In contrast to smoking-associated emphysema, which clinically occurs over decades, HIV-associated emphysema develops over a period of years.9

HUVS is a rare disorder that is typically characterized by urticarial lesions, decreased complement levels, and vasculitis.10 Emphysema in HUVS has been thought to be secondary to vasculitis of the lung resulting in pulmonary damage. Computed tomography typically shows bibasilar panacinar emphysema with bullous changes, air trapping, scattered ground-glass opacities, and minimal fibrotic and inflammatory changes at the lung bases. An elevated ESR and decreased serum complement levels lead to a diagnosis of HUVS.

A variety of environmental factors, particularly from occupational or agricultural exposures, have been studied as possible causes of emphysema. Although classically associated with lung fibrosis, some studies have suggested that these patients may be at higher risk for developing emphysema.11-12

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.