Running Head: Mortality and Cardiopulmonary Events in COPD

Funding support: This study was funded by GSK (study number CTT116855; NCT02164513). The funders of the study had a role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report.

Date of Acceptance: December 6, 2022 | Published Online Date: December 8, 2022

Abbreviations: ACM=all-cause mortality; AE=adverse event; AESI=adverse event of special interest; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV=cardiovascular; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FF=fluticasone furoate; HR=hazard ratio; ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; IMPACT=InforMing the PAthway of COPD Treatment; ITT=intent-to-treat; LABA=long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA=long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist; MedDRA=Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; SMQ=Standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Query; UMEC=umeclidinium; VI=vilanterol

Citation: Wells JM, Criner GJ, Halpin DMG, et al. Mortality risk and serious cardiopulmonary events in moderate-to-severe COPD: post hoc analysis of the IMPACT trial. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2023; 10(1): 33-45. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2022.0332

Note: Data in this manuscript were presented in part at the American Thoracic Society 2021 conference as 2 poster presentations. The respective abstracts were published in: Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2021;203:A2241. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccmconference.2021.203.1_MeetingAbstracts.A2241 and Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:A2240 https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2021.203.1_MeetingAbstracts.A2240

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1,2 Patients with COPD often experience exacerbations which are defined as periods of acute worsening of respiratory symptoms necessitating additional treatment.3 Exacerbations contribute to the overall disease burden experienced by patients with COPD, with patients with frequent or prolonged exacerbations shown to have worse health status and faster disease progression compared with patients with infrequent exacerbations.4 Additionally, exacerbations are also associated with increased medical costs and health care resource utilization, with the highest clinical and financial burden associated with severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization.5-8 Finally, as well as recent prior COPD exacerbations being a risk factor for future exacerbations,3,9,10 studies have indicated that exacerbations are associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality,10-13 and adverse cardiovascular (CV) events.14-16

The InforMing the Pathway of COPD Treatment (IMPACT) trial evaluated once-daily single-inhaler triple therapy with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) /long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist (LAMA) /long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA), fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol versus dual therapy with ICS/LABA, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol, or LAMA/LABA, umeclidinium/vilanterol, in patients with symptomatic COPD and a history of exacerbations.17 Treatment with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol significantly reduced the annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations versus fluticasone furoate/vilanterol and umeclidinium/vilanterol,17 in addition to a significant reduction in all-cause mortality with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol compared with umeclidinium/vilanterol.18 Despite these observed benefits, previous studies have indicated that the use of ICSs may be associated with an increased risk of pneumonia in patients with COPD.17,19-21 However, a recent post hoc analysis of IMPACT demonstrated an overall net benefit of triple therapy in this patient population as indicated by an overall decreased risk of death despite an increased risk of pneumonia in patients treated with ICS-containing therapies.18,22 An additional concern with the use of bronchodilators is their reported association in some studies with an increased risk of CV events,23 although data are conflicting regarding this finding.24 Therefore, it is of interest to consider the risk of cardiopulmonary events when performing benefit-risk assessments of treatments for patients with COPD.

Using the IMPACT trial population, this post hoc analysis aimed to investigate the risk of all-cause mortality during and following a moderate/severe exacerbation, and to further determine the benefit-risk profile of fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol versus fluticasone furoate/vilanterol and umeclidinium/vilanterol by using a cardiopulmonary composite endpoint including exacerbations, pneumonia, CV events, and death during the study period.

Methods

Study Design

The IMPACT trial (GSK study CTT116855; NCT02164513) was a 52-week, phase 3, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter study comparing once-daily, single-inhaler triple therapy with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol with once-daily dual therapy with fluticasone furoate/vilanterol or umeclidinium/vilanterol.17 The trial design has been previously described.17 Patients were randomized (2:2:1) to receive once-daily fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol 100/62.5/25mcg, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol 100/25mcg, or umeclidinium/vilanterol 62.5/25mcg via the Ellipta dry-powder inhaler.

Study Population

Study eligibility criteria have been described previously.17 Briefly, eligible patients were ≥40 years of age with symptomatic COPD (COPD Assessment Test score ≥10 at screening) and either a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) <50% of predicted normal values with ≥1 moderate/severe exacerbation in prior 12 months, or an FEV1 50%–<80% at screening with ≥2 moderate or ≥1 severe exacerbation in prior 12 months. Patients were excluded if they had a current diagnosis of asthma or other known respiratory disease.17 The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from local institutional review boards and independent ethics committees. All patients provided written informed consent.

Endpoints

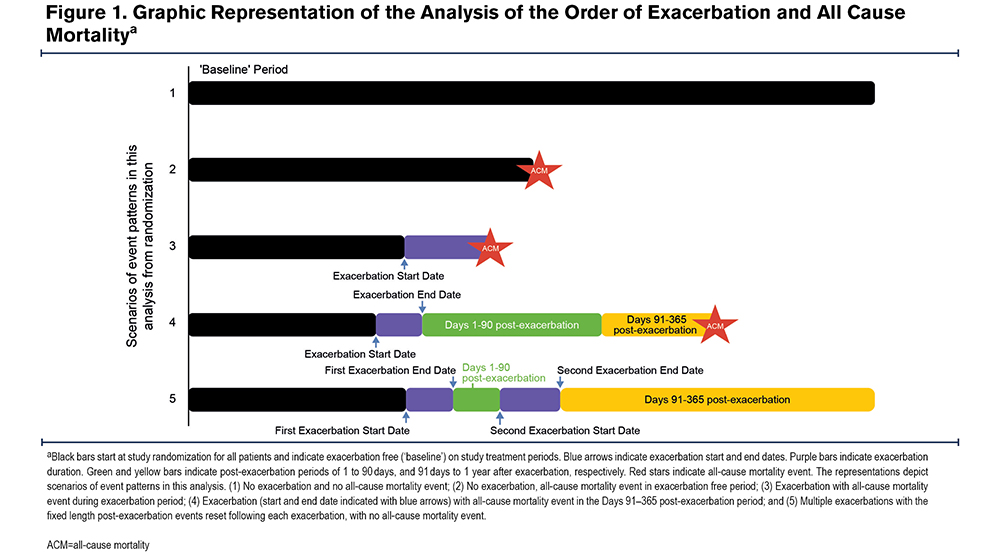

The IMPACT study efficacy and safety endpoints have been described previously.17 Post hoc endpoints included the risk of all-cause mortality during, and in the 1–90 and 91–365 days following the resolution of a moderate or severe exacerbation (Figure 1). The duration of an exacerbation was calculated as exacerbation resolution date or date of death – exacerbation onset date + 1. Resolution of an exacerbation was determined by the physician. The time to first on-treatment cardiopulmonary composite event in patients receiving fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol versus fluticasone furoate/vilanterol and umeclidinium/vilanterol. Patients who experienced worsening COPD symptoms for ≥24 hours or required acute care were assessed by their physician to determine whether an exacerbation or adverse event (AE) should be recorded in the electronic case report form.

On-treatment events were those occurring during the treatment period, with the exception of on-treatment deaths, which are defined below. Exacerbations were defined as either worsening of ≥2 major symptoms (dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence), or one major and one minor symptom (sore throat, cold, fever, and increased coughing or wheezing) for ≥2 consecutive days. Moderate exacerbations were defined as those requiring antibiotics and/or oral/systemic corticosteroids, and severe exacerbations were defined as events resulting in hospitalization or death. On-treatment deaths were defined as those where the actual date of death occurred up to 7 days after the last day of treatment. Events included in the cardiopulmonary composite endpoint were on-treatment severe exacerbation, on-treatment pneumonia AE of special interest (AESI) resulting in hospitalization or death, on-treatment death from any cause, or on-treatment serious CV AESI defined as CVAESI events included in the Standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Queries (SMQs) that resulted in hospitalization or death. In the IMPACT study, CVAESI events were defined as AEs with specified areas of interest for fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, or vilanterol or for the COPD population, and included cardiac arrhythmia (contains selected sub-SMQs), cardiac failure (SMQ), ischemic heart disease (SMQ), hypertension (SMQ), and central nervous system hemorrhages and cerebrovascular conditions (SMQ). AESIs were pre-specified AEs that may be associated with the used of inhaled steroids, LAMA or LABA.17,25

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population of IMPACT, comprising all randomized patients, excluding those who were randomized in error. The risk of all-cause mortality before, during, and post moderate or severe exacerbation versus baseline (the exacerbation-free period of time from randomization to a patient’s first exacerbation or the exacerbation free period following 365 days post the patient’s last exacerbation) was analyzed using a time-dependent repeated measures Cox model on time-to-first event data (where the standard error for the hazard ratio is estimated using a sandwich estimator to account for repeated measures), with covariates of period, treatment group, age group, sex, body mass index, race, ethnicity, geographical region, CV risk factors, smoking status at screening, exacerbation history (≤1, ≥2 moderate/severe), and post bronchodilator percent predicted FEV1 at screening. CV risk factors included past or current history of angina pectoris, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, carotid or aorto-femoral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia.

Analyses were conducted post hoc and hypothesized that mortality is driven by cardiovascular and pulmonary events and a composite cardiopulmonary endpoint comprised of events of comparable clinical importance would provide additional context about risks and benefits of fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol versus fluticasone furoate/vilanterol or umeclidinium/vilanterol in patients with COPD and a history of exacerbations.

The time-to-first cardiopulmonary composite event was assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model with covariates of treatment group, sex, exacerbation history (≤1, ≥2 moderate/severe), geographical region, smoking status at screening, and post-bronchodilator percent predicted FEV1 at screening. The time to event was the start date of that event. For patients who experienced more than 1 of the prespecified events, the time to event was the date of the first event and subsequent events were not used in the analyses. Patients who experienced none of the prespecified events were censored in the analysis at the last known on-treatment time for them.

Results

Patients

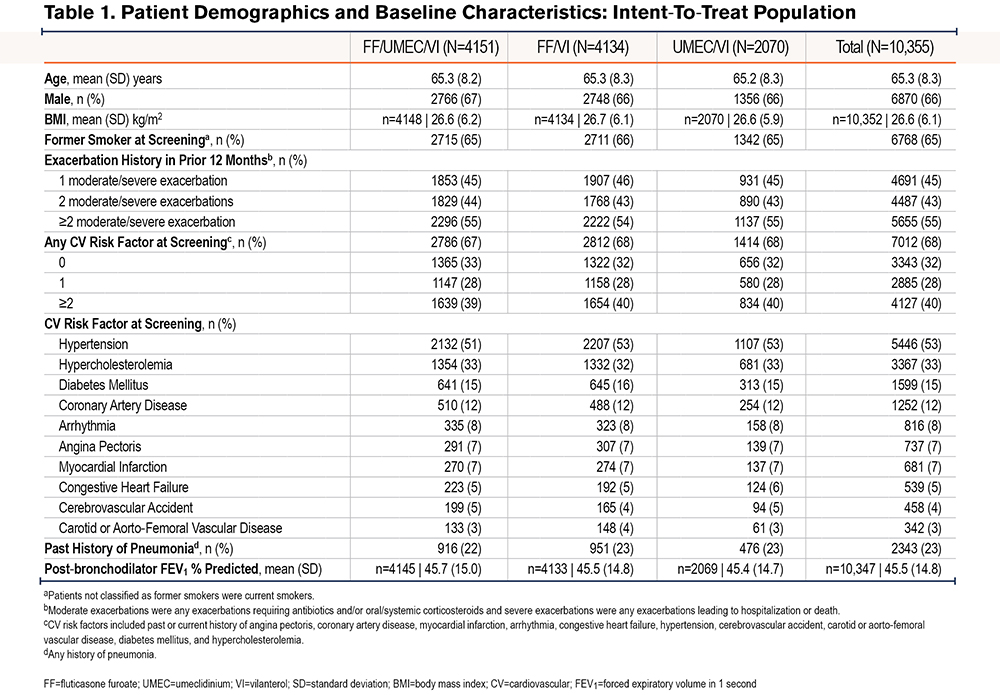

The overall ITT population comprised 10,355 patients (fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol, n=4151; fluticasone furoate/vilanterol, n=4134; umeclidinium/vilanterol, n=2070). Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups (Table 1).

Overall, 758 (18%) patients in the fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol arm, 1040 (25%) patients in the fluticasone furoate/vilanterol arm, and 566 (27%) patients in the umeclidinium/vilanterol arm prematurely discontinued treatment.

Risk of All-Cause Mortality During and Following a Moderate or Severe Exacerbation

Overall Observations

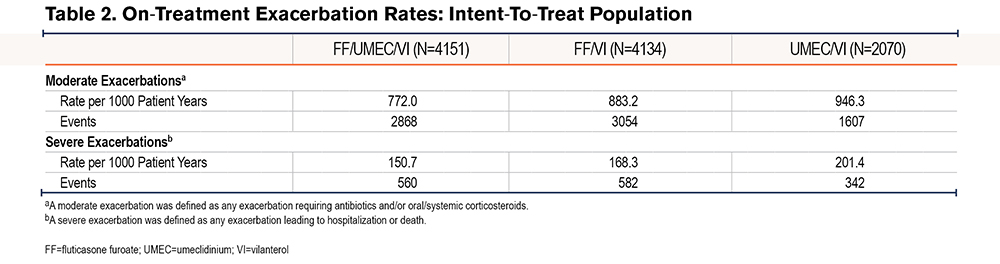

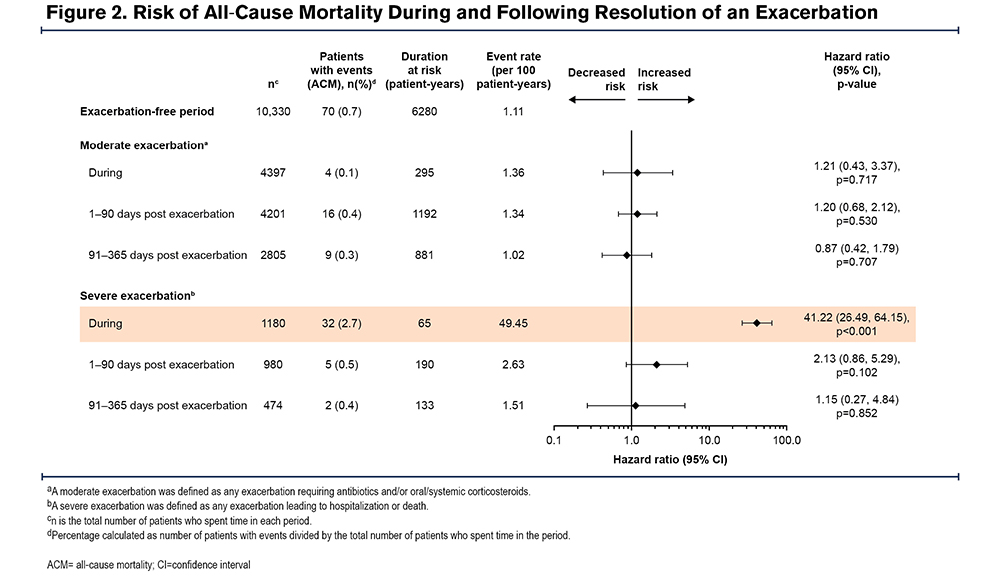

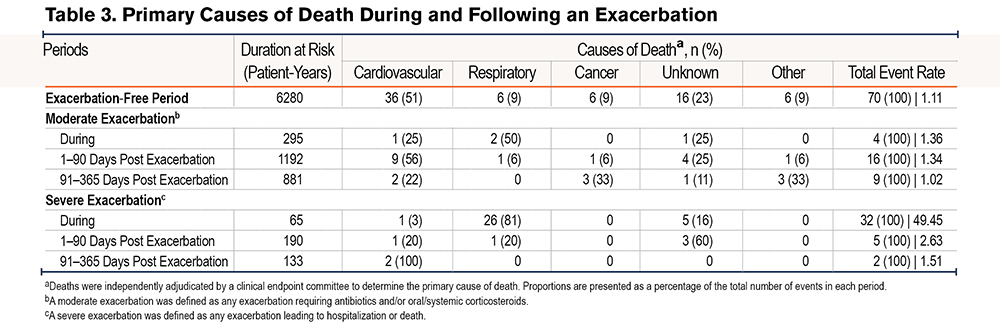

Of the IMPACT ITT population, 4401 (43%) of patients experienced on-treatment moderate exacerbations and 1180 (11%) patients experienced on-treatment severe exacerbations. The most common causes of death in the exacerbation-free period were CV events (36/70 deaths [51%]) and respiratory events were the most common cause of death during exacerbations (moderate: 2/4 deaths [50.0%]; severe: 26/32 deaths [81.3%]) (Table 2). The risk of all-cause mortality significantly increased during a severe exacerbation compared with the exacerbation-free period (hazard ratio [HR]: 41.22 [95% confidence interval (CI): 26.49, 64.15]; p<0.001) (Figure 2). Following resolution of a severe exacerbation, the risk of all-cause mortality decreased with no difference in risk observed at 1–90 days post resolution (HR: 2.13 [95% CI: 0.86, 5.29]; p=0.102) or 91–365 days post resolution (HR: 1.15 [95% CI: 0.27, 4.84]; p=0.852) compared with the baseline period. There was no statistically significant increase in risk of all-cause mortality during a moderate exacerbation compared with the exacerbation-free period (HR: 1.21 [95% CI: 0.43, 3.37]; p=0.717) (Figure 2).

Treatment Effects

On-treatment moderate exacerbations occurred in 1719 (41%) patients in the fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol group, 1795 (43%) patients in the fluticasone furoate/vilanterol group, and 887 (43%) patients in the umeclidinium/vilanterol group, with exacerbation rates highest in the umeclidinium/vilanterol treatment group (Table 3). Additionally, on-treatment severe exacerbations occurred in 447 (11%) patients in the fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol group, 461 (11%) patients in the fluticasone furoate/vilanterol group, and 272 (13%) patients in the umeclidinium/vilanterol group, with exacerbation rates highest in the umeclidinium/vilanterol treatment group (Table 3).

Time to First On-Treatment Cardiopulmonary Composite Event

Overall Observations

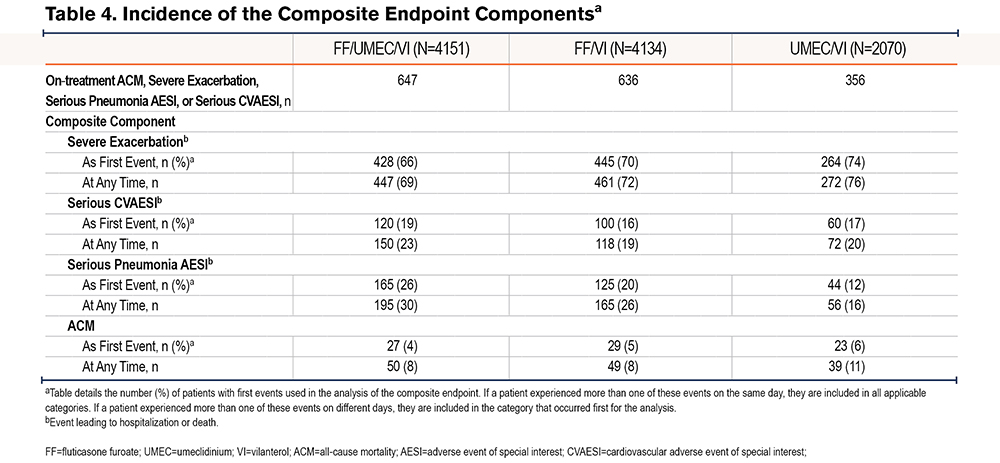

On-treatment cardiopulmonary composite events occurred in 1639 patients (Table 4). Of the individual composite components included in these analyses, the event most likely to occur first was severe exacerbations (Table 4). Almost half of all patients who died experienced at least one other contributing event first. For first events only, severe exacerbations were the main driver of the composite endpoint.

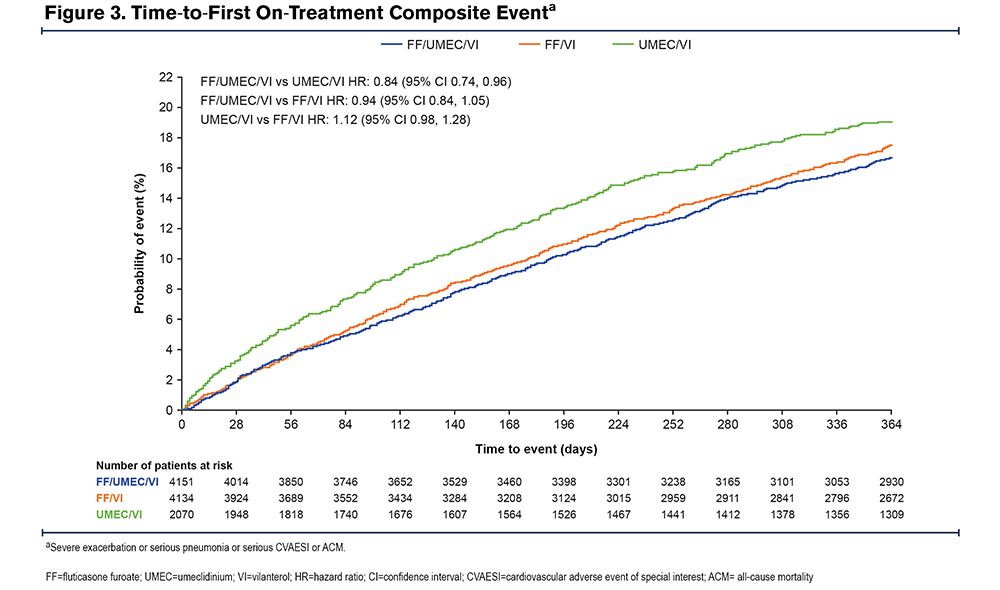

Treatment Effects

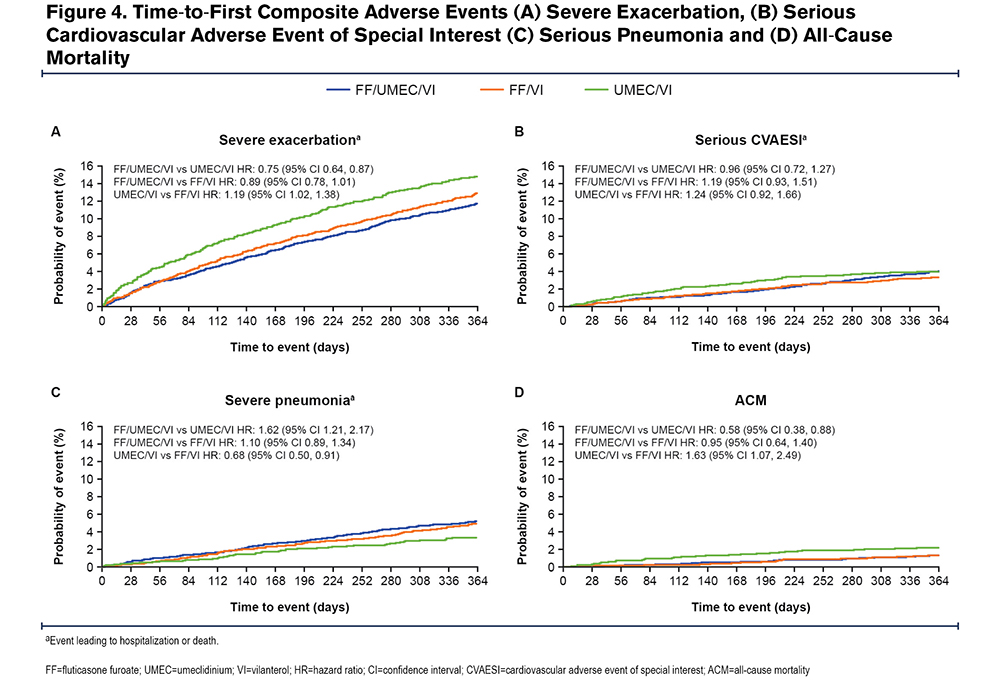

On-treatment cardiopulmonary composite events occurred in 647 (16%), 636 (15%), and 356 (17%) patients receiving fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol, and umeclidinium/vilanterol, respectively. The probability of an on-treatment composite event occurring prior to Day 365 for fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol was 16.7% (95% CI: 15.5%, 17.9%), compared with 17.5% (95% CI: 16.3%, 18.8%) for fluticasone furoate/vilanterol and 19.1% (95% CI: 17.3%, 21.0%) for umeclidinium/vilanterol (Figure 3). Fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol significantly reduced the risk of an on-treatment cardiopulmonary composite event versus umeclidinium/vilanterol with a 16.5% reduction in risk (95% CI: 5.0%, 26.7%; p=0.006). The point estimates for the reduction in the risk of an on-treatment composite event favored fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol over fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (6.2% reduction [-4.7%, 15.9%]; p=0.255), and fluticasone furoate/vilanterol over umeclidinium/vilanterol (11.1% reduction [-1.3%, 21.9%]; p=0.077), but these differences were not statistically significant.

Although overall serious pneumonia incidence was higher in the ICS-containing groups, mortality and hospitalization for COPD was lower in the ICS groups. For serious CVAESI events, there were no differences between treatments observed (Figure 4; Table 4).

Discussion

These post hoc analyses of the IMPACT study including patients with symptomatic COPD at risk of exacerbations showed that the risk of all-cause mortality significantly increased during a severe exacerbation and subsequently decreased following the event. Cardiopulmonary events were the most common causes of mortality before an exacerbation, highlighting the underlying CV risk in this population, whereas pulmonary events were the most common causes during an exacerbation. Additionally, these analyses demonstrated that treatment with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol significantly reduced the risk of a cardiopulmonary composite event compared with umeclidinium/vilanterol, demonstrating a favorable benefit–risk profile of once-daily fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol triple therapy compared with umeclidinium/vilanterol dual therapy in patients with symptomatic COPD and a history of exacerbations.

The results from this analysis demonstrated a 41-fold increased risk of mortality during a severe COPD exacerbation compared with the exacerbation free period, and a 2-fold increased risk during 1–90 days post resolution. However, the difference observed between the risk of all-cause mortality at 1–90 days post resolution and 91–365 days post resolution compared with the baseline period was not significant, likely due to the low number of events. These results are consistent with previous studies, which have also linked severe COPD exacerbations with increased risk of mortality.10,11,13 In particular, the results of a previous retrospective study showed that risk of death was increased approximately 14-fold with the occurrence of at least one severe exacerbation in the previous 12 months.11 Furthermore, a large-scale retrospective study in patients with COPD reported that the time to each subsequent exacerbation decreases with increasing exacerbation frequency, while increasing the risk of death up to 5-fold after their 10th hospitalization compared with the risk after their 1st hospitalization.13 Interestingly, the most common cause of death during the exacerbation-free period was a CV event, suggesting that cardiac risks need to be addressed in the general COPD population, regardless of their exacerbation history status.

The current analysis also found that severe exacerbations were the most common driver of cardiopulmonary AEs. As severe exacerbations are associated with high medical costs and health care resource utilization, the reduction of severe exacerbations and survival benefits conferred by fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in IMPACT indicates the potential to significantly decrease the clinical and economic burden associated with COPD.5-8

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease strategy document recommends ICS be prescribed to patients with COPD to reduce exacerbation frequency.3 Accordingly, a previous post hoc analysis of IMPACT, with additional vital status data collected up to Week 52 for 99.6% of the ITT population, demonstrated that all-cause mortality was significantly reduced by 28% with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol compared with umeclidinium/vilanterol (absolute risk reduction: 0.83%), but not compared with fluticasone furoate/vilanterol.18 Similarly, in a post hoc analysis of the ETHOS trial, which included a final retrieved dataset with additional Week 52 vital status information comprising 99.6% of the 8509 patients in the ITT population, twice-daily single-inhaler budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol reduced the risk of on-/off-treatment all-cause mortality by 49% versus glycopyrrolate/formoterol (absolute risk reduction: 1.24%), but not compared with budesonide/formoterol.26

As ICS use is associated with reduced exacerbation risk, the results from the current analyses coupled with the overall mortality results suggest that the addition of ICS is conferring survival benefits. Therefore, survival benefits observed with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in IMPACT may be driven by a reduction in exacerbations. This is clinically significant given that patients in IMPACT were at high risk of future exacerbations, with eligibility criteria requiring either an FEV1 <50% of the predicted normal value and a history of ≥1 moderate or severe exacerbation in the prior year, or an FEV1 of 50%‒80% of the predicted normal value and ≥2 moderate exacerbations or 1 severe exacerbation in the previous year.17

Although these analyses indicate clear exacerbation and survival benefits with the addition of an ICS to the therapeutic regimen, concerns have been raised about the increased risk of pneumonia in patients with COPD.17-21 Results from a Cochrane review concluded that ICS delivered alone or in combination with a LABA can increase serious pneumonias in patients with COPD,19 and results from the IMPACT and Efficacy and Safety of Triple Therapy in Obstructive Lung Disease (ETHOS) trials indicated that the risk of first on-treatment pneumonia was significantly higher in patients receiving ICS/LAMA/LABA compared with LAMA/LABA therapy.17,26 However, the exacerbation and all-cause mortality benefits of using triple therapy to treat COPD has been shown to outweigh this risk. A previous analysis of the IMPACT trial evaluating composite exacerbation or pneumonia outcomes showed that despite higher incidence of pneumonia in the ICS-containing arms, a favorable benefit-risk profile was exhibited with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol versus fluticasone furoate/vilanterol and umeclidinium/vilanterol.22 The results of the current analysis are consistent with these findings in that, although overall pneumonia was higher in the ICS containing groups, mortality and hospitalization for COPD was lower in the ICS-containing treatment arms.

Another key concern for patients and clinicians is that patients with COPD are at increased risk of acute CV events.14 Several studies have demonstrated the additional risk of adverse CV events in patients who experience COPD exacerbations.14-16 Furthermore, acute COPD exacerbations and acute pulmonary embolism events may mask each other due to similar clinical presentations.27 The use of bronchodilators has been associated with increased risk of CV events in a review23 ; however, evidence is conflicting with some studies showing no increase in events. For example, the Study to Understand Mortality and Morbidity in COPD (SUMMIT) trial, which was conducted in a patient population with COPD and at heightened risk for CV events, found no evidence of increased CV events in patients treated with an ICS/LABA combination.24 Even though entry requirements for the IMPACT trial were less strict with respect to CV events compared with other trials (e.g., patients with New York Heart Association Class I–III heart failure, history of previous myocardial infarction >6 months before entry, and unstable or life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia requiring intervention >3 months before entry were eligible),17,26,28 results from the current analysis found that triple therapy with ICS/LABA/LAMA significantly reduced the risk of an on-treatment cardiopulmonary composite event versus LABA/LAMA.

These analyses have several key strengths and limitations. The IMPACT patient population was large, well characterized, and potentially generalizable to real-world patients with moderate to severe COPD. The study also included the independent adjudication of deaths. However, it should also be noted that when time-to-first analysis is used, the effect of benefits may be underestimated as only the first events are included. Dependence of events cannot be demonstrated in a non-randomized comparison. No recurrent event analysis was performed because the composite endpoint included death (after which no further events could occur) and different events could be quite different in their severities and outcomes. Profiling individual patients with multiple cardiopulmonary events would not be expected to change the conclusions from the time-to-first analyses, since there were a limited number of overlapping events in the IMPACT study. The overall incidence of mortality events was low, and in addition, the data were collected according to guidance such that, if a patient died during the exacerbation event (between the start and stop date) the exacerbation was considered severe and would be recorded as such in the database, even if the exacerbation started as moderate (i.e., worst severity for the entire period was recorded).

The results from these analyses of the IMPACT trial emphasize the substantial mortality risk associated with severe COPD exacerbations, the importance of preventing exacerbations as a treatment goal, and the need to optimize treatment in patients at risk of exacerbations. Further, they highlight the importance of the underlying CV risk in this population. Treatment with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol triple therapy confers a favorable benefit-risk profile compared with dual therapy in patients with symptomatic COPD and a history of exacerbations.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: J. Michael Wells takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors had full access to the data in this study, note adherence of the study to the protocol, and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis, and responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. All authors discussed and interpreted the results, contributed to the data analyses, contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Editorial support in the form of preparation of the first draft based on input from all authors, and collation and incorporation of author feedback to develop subsequent drafts was provided by Alexandra Berry, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, United Kingdom, part of Fishawack Health and was funded by GSK.

Data sharing: Anonymized individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com

Declaration of Interest

JMW received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, and GSK, grant support from the National Institutes of Health, and contracted research support from Bayer AG, ARCUS-Med, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Mereo BioPharma, Verona, and Grifols. GJC received personal fees from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSA Medical, Eolo, GSK, HGE Technologies, Novartis, Nuvaira, Olympus, Pulmonx, and Verona. DMGH received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, and Pfizer, and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis. MKH reports personal fees from Medscape and Integrity, as well as consulting fees from GSK, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Pulmonx, Teva, Verona, Merck, Mylan, Sanofi, DevPro, Aerogen, Polarian, Regeneron, Altesa Biopharma, and United Therapeutics. She has received royalties from UpToDate, WW Norton, and Penguin Random House. She has received payment or honoraria for consultancy from Cipla, Chiesi, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Medscape, and Integrity. She has served on boards or scientific committees for the COPD Foundation, the American Lung Association, Emerson School, and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, and has been a volunteer spokesperson for the American Lung Association and is a deputy editor of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. She has received either in-kind research support or funds paid to the institution from the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Sunovion, Nuvaira, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gala Therapeutics, Biodesix, the COPD Foundation, and the American Lung Association. She has participated in data safety monitoring boards for Novartis and Medtronic with funds paid to the institution. She holds stock options from Meissa Vaccines and Altesa BioPharma. RJ, DAL, and DM are GSK employees and hold GSK stocks/shares. PL has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, and GSK. FJM has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Gala, GSK, Novartis, Polarean, Pulmonx, Sanofi/Regeneron, Sunovion, Teva, Theravance/Viatris, and Verona; grant support from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GSK, and Sanofi/Regeneron; payment or honoraria from UpToDate for participation in COPD continuing medical education activities; and participated in an event adjudication committee for MedTronic. FJM states that AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GSK are partners of the SPIROMICS program and partners in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) CAPTURE validation study; Novartis, Sanofi/Regeneron, Sunovion, and Teva are partners of the SPIROMICS program; Theravance/Viatris are partners in the NHLBI CAPTURE validation study. DS declares consulting fees from Aerogen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, CSL Behring, Epiendo, Genentech, Glenmark, GSK, Gossamerbio, Kinaset, Menarini, Novartis, Pulmatrix, Sanofi, Synairgen, Teva, Theravance, and Verona. RAW has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Contrafect, Roche-Genentech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Verona, Theravance, AbbVie, GSK, Chemerx, Kiniksa, Savara, Galderma, Kamada, Pulmonx, Kinevant, Vaxart, Polarean, Chiesi, 4D Pharma, Puretech, and grant support from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Verona, Genentech, Boehringer Ingelheim, and 4DX imaging. He has received payment for expert testimony from the United States Government and Genentech and support for attending meetings and/or travel from AstraZeneca. Additionally, he has received editorial support from GSK, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck Foundation and has served on the Board of Directors and the Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee for the COPD Foundation, and on a Scientific Advisory Board for the American Lung Association. He is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

ELLIPTA is owned by or licensed to the GSK Group of Companies.