Running Head: COPD and Sexuality

Funding Support: The project was funded by the Swiss Lung Association (no grant number available),the Verein Lunge Zurich grant (no grant number available), AstraZeneca (unrestricted grant, no grant number available), GlaxoSmithKline MG Ref Nr 2019-0141_0001 (unrestricted grant), Novartis Pharma jP3 Number: C119107493S8 (unrestricted grant), and OM Pharma (unrestricted grant, no grant number available)

Date of Acceptance: February 16, 2023 | Published Online Date: February 24, 2023

Abbreviations: COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COSY=Communication about SexualitY; HCPs=health care professionals; LWWWCOPD=Living Well With COPD

Citation: Steurer-Stey C, Dalla Lana K, Strassmann A, et al. Development of a communication instrument to address sexuality in COPD: COSY. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2023; 10(2): 148-158. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2022.0355

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (2314KB)

Introduction

Quality of life is a widely accepted, if not the most relevant, outcome measure for persons with a chronic illness, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).1 Human sexuality is a universal part of living that impacts quality of life but it is often ignored when caring for people affected by COPD.2,3 Despite the fact that intimacy and sexual activity can be markedly affected by breathlessness, fatigue, and anxiety,4,5 sexuality is rarely addressed by health care professionals (HCPs) or patients. Stereotypes of older and chronically ill people often ignore the significance of intimacy and sexual fulfillment with respect to quality of life and emotional well-being.

The English Longitudinal Study of Aging, a representative survey of a cohort aged 50 to >90 years captured information on sexual behaviors, attitudes, concerns, sexual function, and quality of intimate relationships as people grow older.6 The data demonstrated that although sexual activities decline with increasing age and chronic conditions, older people judge sexual activity to be important for their well-being and do continue to have active sex lives. However, older people felt their concerns about sexual issues were not taken seriously and missed conversations and advice.6,7 When sexual- function and intimacy are reduced by illness, treatment, or anxiety, well-being and quality of life worsen in people affected by COPD.4,8 Concerns about sexual activity are just as legitimate as concerns about any other physical activity in people with COPD and should be addressed in a respectful way.

Shyness and discomfort of HCPs and patients, as well as lack of the basic sexuality communication skills of HCPs and low health literacy of people with COPD, are reasons why sexuality is often ignored in the communication between HCPs and patients.9,10,11 Our aim was to develop a communication instrument intended as a “door opener” to promote conversation and counseling on sexual issues in the care of people living with COPD and to support HCPs and patients to start the communication about sex. To our knowledge, this is the first COPD-specific instrument focusing on communication about sexuality and we are not aware of similar instruments for other chronic conditions.

Methods

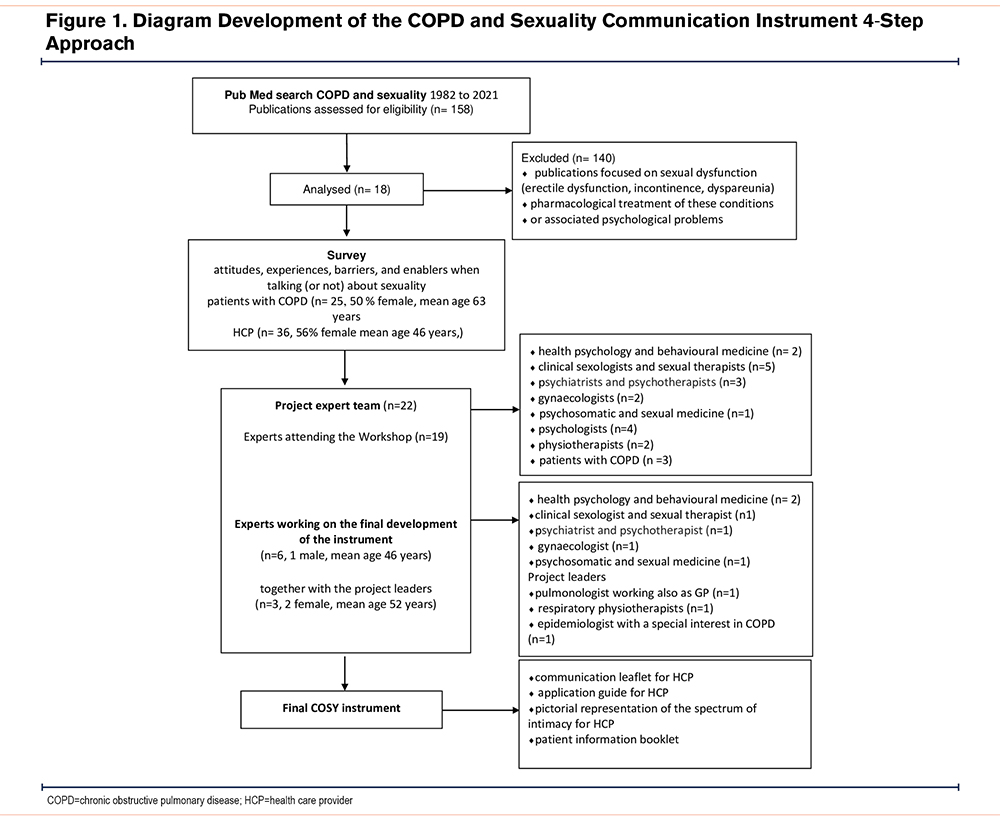

We iteratively developed and validated the communication instrument in 4 steps (Figure 1).

Step 1: Literature Search

We performed a limited literature search in PubMed applying a search strategy using the terms COPD and sexuality. We excluded publications with a focus on sexual dysfunction in the title (erectile dysfunction, incontinence, dyspareunia), pharmacological treatment of these disorders, or associated psychological problems. We extracted information focusing on: (a) problems reported by persons living with COPD in maintaining sexual activity, (b) needs from the patient’s perspective, (c) limitations and barriers on the part of HCPs, and (d) communication strategies, enablers, suggestions, and counseling interventions.

Step 2: Survey Among Health Care Providers and COPD Patients About Their Attitudes, Experiences, Barriers, and Enablers When Talking (or Not) About Sexuality

Based on the information in the literature and the experience of the participating experts, we developed one questionnaire for COPD patients and one for HCPs (online supplement). We piloted the questionnaires for comprehensibility and applicability with 3 general practitioners, one pulmonologist, 3 non-doctoral HCPs, and 4 COPD patients. Based on the feedback, the questionnaires were adapted.

Within a 3-month period, 28 patients with COPD in primary care were asked to take part in a survey on sexuality in COPD patients. It was explained to them that the answers and data would be fully anonymized. Since the survey did not fall under the Human Law for Medical Research, because no identifiable medical data were collected, the ethics committee issued a waiver (BASEC Nr. Req-2019-01044) for the survey.

Twenty-five patients gave their written informed consent, filled in the questionnaires at home, and returned them by pre-paid envelopes to the Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Prevention Institute at the University of Zurich (response rate of 89%). Fifty health professionals were contacted and informed by email and the questionnaire was attached with the option to complete the questionnaire and send it back via email or print it out and return it anonymously per post. Thirty-six completed the questionnaire (response rate of 72%).

Step 3: Workshop With an Interdisciplinary Project Expert Team

A project expert team with HCPs from various disciplines and 3 patients with COPD was set up. We identified 24 national specialists active in research and/or practice, and persons living with COPD through professional networks, literature, publications, media, and national institutions. We contacted them by email and informed them about our intention to create a multidisciplinary project team with expertise in sexuality and chronic disease. We asked if they would be interested in collaborating on developing a practical, user-friendly communication aid that could serve as a “door opener” for initiating communication about sexual topics in patients with COPD. Nineteen experts (1 male, mean age 48.3 years) from health psychology and behavioral medicine (n=2), clinical sexuality and sexual therapy (n=5), psychiatry and psychotherapy (n=3), gynecology (n=2), psychosomatic and sexual medicine (n=1), psychology (n=4), and physiotherapy (n=2) agreed, and we invited them to a half-day workshop. We, the initiators of the project consist of a pulmonologist and general practitioner, a respiratory physiotherapist, and an epidemiologist with a special interest in COPD. Three COPD patients (59 years, 68 years, and 76 years of age, one female) were also involved as experts. They agreed to an interview but did not want to participate in the workshop.

The workshop started with a detailed introduction round explaining the personal motivation to participate and giving personal examples and experiences when talking about sexuality in elderly and chronically ill people. It was followed by an introductory lecture about COPD and the disease-specific problems that can interfere with sexuality.

We discussed the literature review and the survey results as a basis for the contents, the when and how to address communication about sexuality, and a possible design of the communication instrument. By the end of the day, we had reached a consensus on the crucial issues in terms of the format, contents, and usability of the communication material.

Step 4: Development of the Communication Instrument

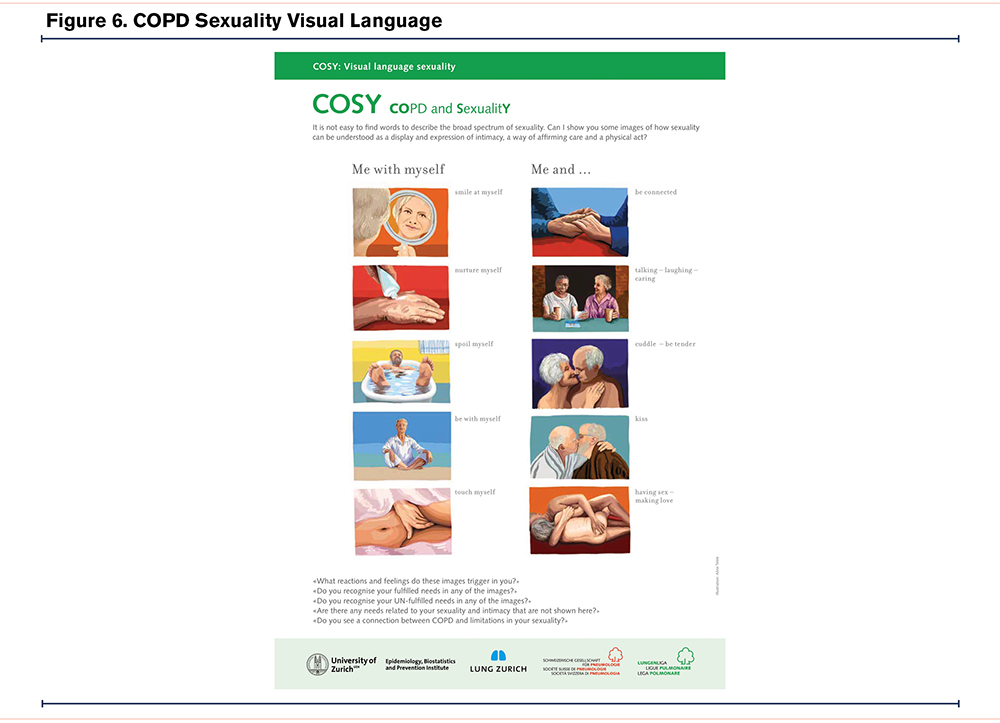

The workshop resulted in a consensus that the communication instrument should be helpful for both professionals and patients and provide tools for both users. Initially, a first draft of a paper-based communication leaflet for HCPs was designed. The desktop helper series of the International Primary Care Respiratory group12 served as a template for the leaflet. In several review rounds among the members of the project team, feedback on the draft was collected and integrated into the final communication leaflet (Communication about Sexuality in COPD [COSY]). During this process, a user manual was created as an aid in clinical practice with instructions on how to use the communication leaflet based on the principles of motivational interviewing. The third COSY tool is a pictorial representation of the spectrum of intimacy. To select the images, we considered 4 aspects: relationship status, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and a broad representation of intimacy and sexuality. This was also the case for tool 4, the picturized patient information booklet.

Besides the iterative development and testing of face validity described above we reached out to the European Lung Foundation (ELF)13 and the COPD Foundation14 for further external validation. We introduced the instrument to representatives of ELF and the COPD Foundation who expressed much interest and appreciation for addressing the topic of sexuality in COPD. Kristen Willard, MS, Executive Vice President of Public and Professional Education at the COPD Foundation, sent the COSY materials to the patient and caregiver advisory board and met with them to discuss the material in detail. Jessica Denning who is responsible for communication and education at the ELF edited the English version of the COSY patient booklet.

Results

Step 1

The PubMed search “COPD and sexuality” resulted in 158 hits (from 1982 to 2021). We screened and read the 158 abstracts but excluded the majority because the publications focused on sexual dysfunction in the title (erectile dysfunction, incontinence, dyspareunia) and/or pharmacological treatment of these conditions or associated psychological problems. We examined the content of 18 publications in detail.2-5,8,9,15-26 They showed that a substantial proportion of persons living with COPD perceive problems and miscommunication around sexual issues. The most frequent problems reported in maintaining sexual activity were fatigue, COPD symptoms, anxiety because of breathing problems, activity intolerance, and loss of positive body image.8,15 The needs formulated covered the issues of being more comfortable with breathing and sex, taking the stress out of intercourse, energy management, and the patient expectation that health professionals should ask them about any sexual concerns they might have and to obtain the support they require to talk about their sexual needs.17,26 Barriers on the part of the health professional were mainly shame and lack of specific training on how to initiate communication.17,19 Across publications it was consistently reported that this topic is still rarely addressed in clinical practice and research and that there is a need for better communication and disease-specific instruments that can help HCPs to include such measures and assess sexual problems routinely in medical care for persons living with COPD.2,3,24

Step 2

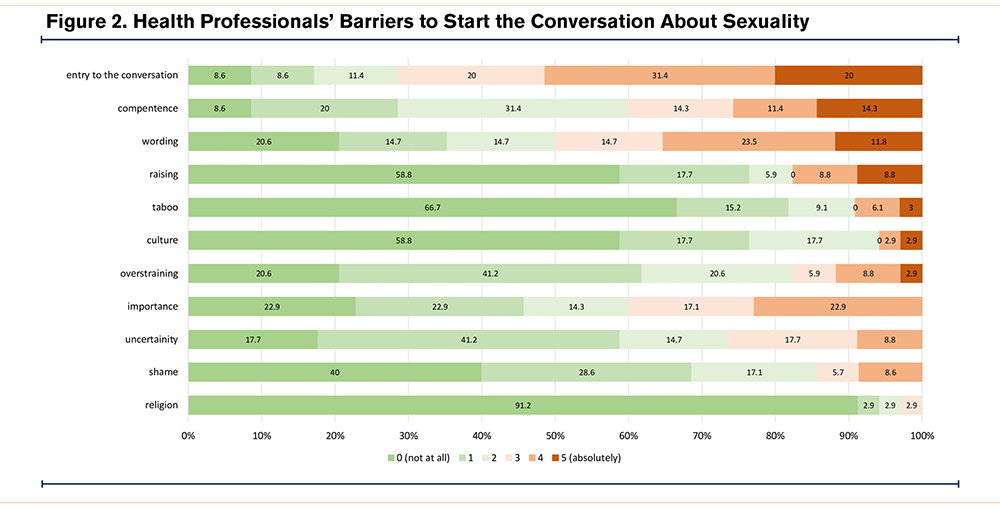

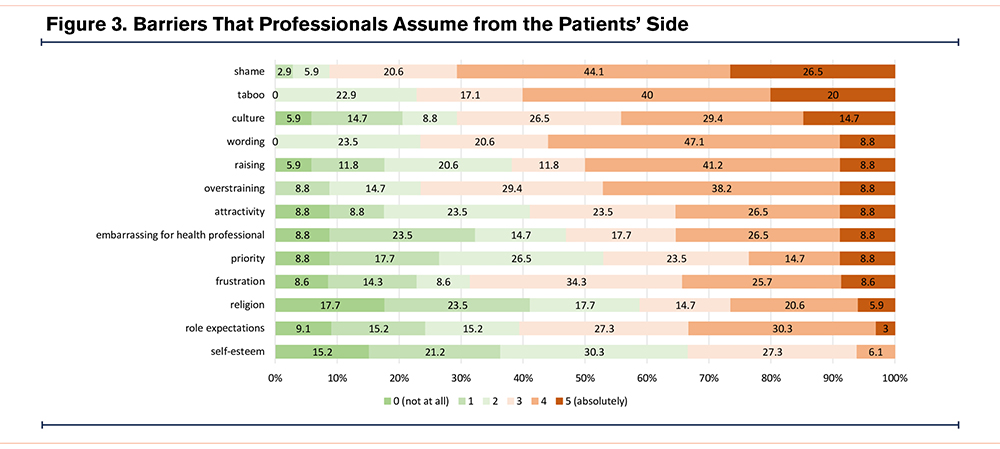

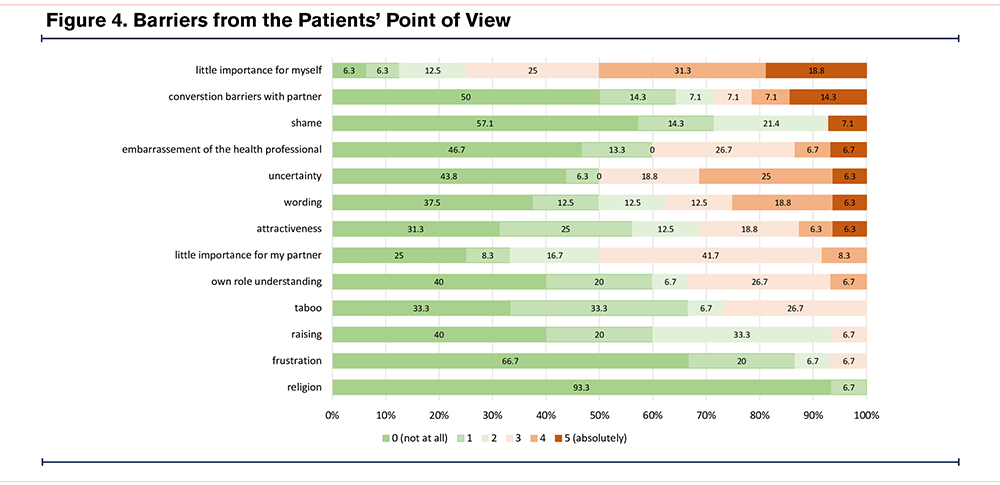

In the survey, 25 patients with COPD (mean age 63 years, 50% female, modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale score 2.1±1.3, 61% in a relationship) from primary care and 36 HCPs (mean age 46 years, 56% female, GPs 33%, lung specialists 19%, nurses/physiotherapists 47%) participated. Of the patients, 83% reported that they had never been asked about their sexuality since being diagnosed with COPD, although it was an important topic for 1 in 2 patients. Of the HCPs, 86% considered sexuality important for quality of life, 69% wanted to address it but 49% never did. The main barriers for HCPs in our survey were a lack of specific training on how to initiate communication and a misconception with respect to patients’ barriers which were not shame or religion, but conversation barriers between them and their partners and wording (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4). The results of the survey were presented as an abstract at the 2020 European Respiratory Society Meeting.27

Step 3

Of 19 experts, 14 (one male, mean age 48.4 years) took part in the half-day workshop led by a pulmonologist and a respiratory physiotherapist.

Based on the results of the literature review and survey, we discussed the content and form of the communication instrument and when and how to initiate communication about sexuality. There was a consensus that the COSY instrument should be helpful for HCPs and patients and provide tools for both users. Finally, 6 of the experts (one male, mean age 46 years) collaborated with us further on the development of the instrument (Figure 1).

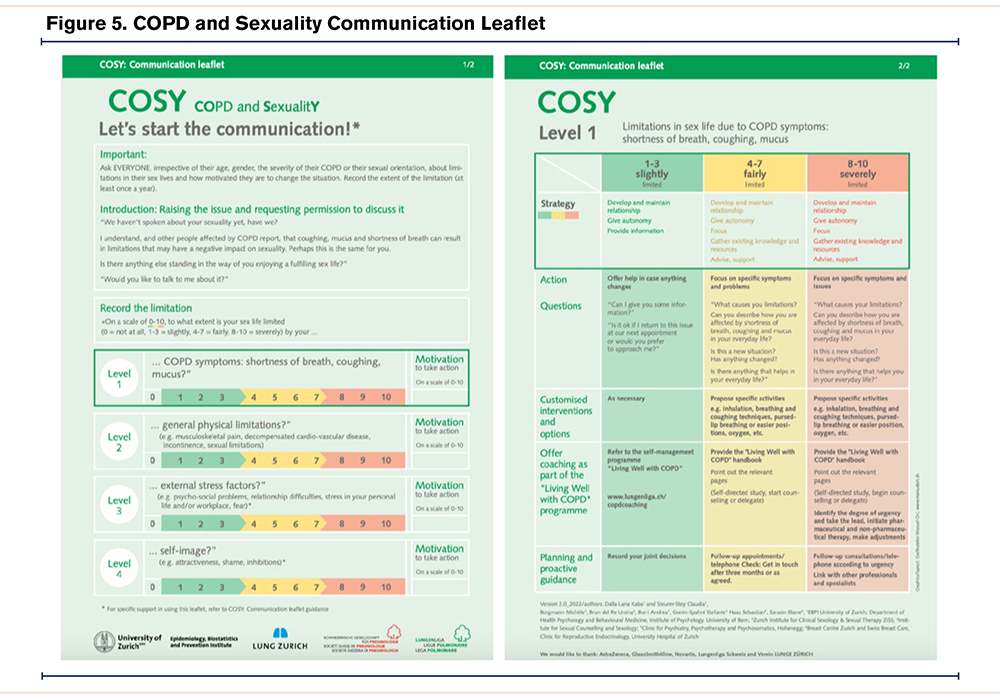

Step 4

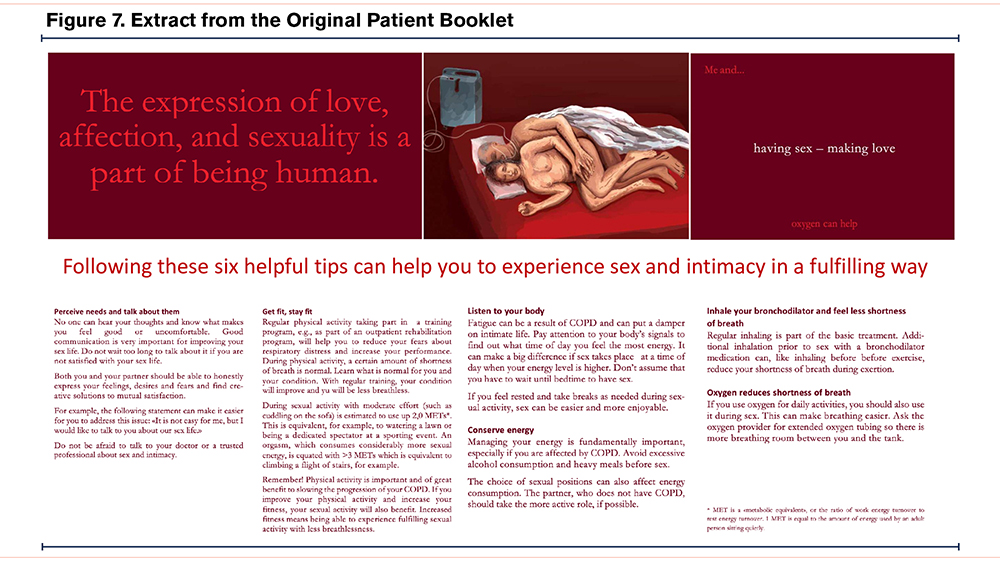

The COSY instrument we developed consists of 4 tools: a communication leaflet for HCPs, an application guide, a pictorial representation of the spectrum of intimacy for HCPs, and an information booklet for patients. The communication leaflet (Figure 5) covers 4 different domains that can limit sexual activity in people with COPD (limitations due to COPD symptoms, general physical condition, self-image, or external stress factors). The application guide instructs HCPs on how to best work with the communication leaflet following an active listening and motivational interviewing approach. It supports them with concrete instructions and example questions on sex and intimacy but also reminds the user to refer and collaborate with other providers and appropriate specialists. We complemented the COSY instrument with a pictorial representation of the spectrum of intimacy for HCPs (Figure 6) and a patient information booklet combining a pictorial approach and 6 helpful tips and instructions that could help COPD patients to enhance their sexual experience (Figure 7). The entire patient booklet is available in the online supplement.

We were able to test the instrument externally thanks to the COPD Foundation. The members of the patient and caregiver advisory board felt the topic is often overlooked but essential to overall health and well-being. They very much appreciated the topics addressed, the illustrations, and the fact that the materials addressed intimacy and sensuality rather than sex alone. They also liked that the instrument highlights the importance of communication between persons with COPD and their partners as well as between the HCP and the patient. Despite their very positive response to the COSY materials, they felt that the U.S. health care system was not structured to be conducive to such discussions, with patients seeing their doctors for only short consultations at a time. They also thought that HCPs were ill-equipped to have these conversations. All 4 COSY tools can be viewed and downloaded for free on the Lung League Switzerland website.28

Discussion

Based on information in the literature, the results of a survey with patients and HCPs, and the expertise of specialists, we developed, to our knowledge, the first COPD-specific instrument (COSY) to facilitate communication about sexuality and address the needs of both patients and caregivers. Despite the high prevalence of sexual dissatisfaction among patients with COPD, communication about sexuality very often remains taboo and is rarely addressed in practice nor incorporated in quality-of-life measures for COPD patients.2,3

Our survey results are in line with Zysman et al and others5,27,29 reporting that 80%–90% of patients with COPD confirmed that the topic was never raised by doctors or patients themselves, but that the majority would like to talk about sexual matters. Explanations as to why this did not happen are similar in our data24 compared to others.11,29 Reported reasons are shyness and embarrassment of HCPs and the lack of basic skills.

In addition, there are mutual misconceptions that talking about the issue will make the other person uncomfortable15,17,27 as well as the lack of support tools to address sexuality with greater confidence.3

The COSY instrument is such a supportive tool addressing the needs of both caregivers and patients. COSY includes approaches to solutions and provides concrete assistance for communication and counseling. An important message provided by the COSY instrument for HCPs who care for people living with COPD is that one must not be a sexologist to be able to start communications about sexuality. Professionals who understand that intimacy and sexual relationships are important parts of life and offer counseling to troubled persons might improve the well-being of persons living with COPD. Evidence from chronic cancer disease suggests that discussions of sexuality can be helpful and sexual activity can be beneficial for health status and quality of life.30,31

Our survey also showed that for persons with COPD, communication about sexuality requires a trusted relationship with the HCP and that for every other person, communication with the partner was a problem. The COSY instrument highlights the importance of communication between the partner and the person with COPD as well as the HCP and patient. Hahn12 described a support group program that helped persons with COPD become more knowledgeable and comfortable discussing sexual matters with HCPs and partners. Proper communication, health information, and improved health literacy are needed for people living with COPD to get them involved and empowered.10 An important part of the COSY instrument is the patient information booklet. It allows patients and/or partners to better understand and use health information by providing concrete advice. Eleven illustrations that speak for themselves cover the broad spectrum with possible expressions and manifestations of caring and intimacy. The COSY patient booklet allows flexibility in the timing and delivery of information and is easy to read. It fulfills the key points highlighted for quality and effectiveness in a recent review article on the role, contents, and design of patient information leaflets in COPD in terms of sexual health communication.17

The COSY instrument is available in English, German, French, and Italian for wider dissemination and could be used in patient-physician consultations and within pulmonary rehabilitation and self-management programs. Thoughts from the COPD Foundation patient and caregiver advisory board on an effective approach in the United States included making sexuality and intimacy a component of a larger series/educational program, for example as part of pulmonary rehabilitation and a larger self-care educational campaign (e.g., pamphlet or flyer).

To approach sexual activity as any other physical activity and correlate it with the energy requirements, such as walking or household tasks, to determine an individual's activity and sexual activity tolerance, could change practice. We and others have proven with the “Living Well with COPD" (LWWCOPD)intervention that it is possible for persons living with COPD to live a healthier and more fulfilling life.32,33 Developing a partnership with patients is central in LWWCOPD and might, therefore, serve as an ideal framework to consider sexuality, identify sexual needs, and promote and facilitate communication and counseling about sexuality. The next steps planned are to include the topics of intimacy and sexuality in the LWWCOPD that is implemented in clinical practice in Switzerland. HCPs who apply the LWWCOPD program must pass training modules. The topic of sexuality and communication about sexuality in COPD will be an extra module integrated into the training and thereby more HCPs will be empowered to apply and work with the COSY instrument and to test its use in clinical settings.

The main limitation of our work is that the evaluation of the COSY tools is limited so far. However, we cannot see any harm either for patients or for HCPs to work with COSY, which is based on respect, free will, and autonomy. Working with COSY can serve as a resource for HCPs and patients. Future work needs to include implementation studies that examine the acceptance of the instrument in larger and more diverse populations during the clinical encounter and should evaluate what speaks for and against the use of COSY for patients and HCPs. Ideally, a randomized controlled trial would test whether communication and counseling about sexual activity using the COSY tools versus not using them increases well-being, improves the experience of sexuality, and serves as motivation to increase or maintain long-term physical activity.

Conclusion

The COSY instrument creates opportunities to overcome taboos and clichés, start communication, and be more sensitive to the sexual concerns of COPD-affected people in daily practice, thereby supporting a more holistic consideration of quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: C. Steurer-Stey and K. Dalla Lana were the project initiators, project leaders, and main authors of the communication instrument. They performed the literature review and survey. A. Strassmann and A. Frei contributed to the development and analyses of the questionnaires for the survey. S. Gonin-Spahni, M. Borgmann, U. Brun del Re, S. Haas, E. Sarasin, and A. Burri were members of the project expert team. The expert team, C. Steurer-Stey, K. Dalla Lana, and Milo Puhan discussed the results of the literature review and the survey as a basis for the contents, the “when and how” to address communication about sexuality, and the design of the communication instrument. All authors contributed to the development and final version of the COSY instrument. All authors read and contributed to this manuscript.

We thank the participants of the survey, the 3 patients on the project expert team, Manuel Ort for the graphical work on the communication leaflet and application guide, and Aline Telek for the graphics and illustrations of the patient booklet and the pictorial representation of the spectrum of intimacy for health professionals. We are grateful to the Swiss Lung Association for the translation and free dissemination of the COSY instrument.

We are particularly grateful to Kristen Willard, MS, from the COPD Foundation who discussed the COSY materials in detail with the patient and caregiver advisory board and Jessica Denning from the ELF who edited the English version of the COSY patient booklet.

Declaration of Interest

Claudia Steurer-Stey receives grants from AstraZeneca, GSK, OM pharma, consulting fees as an advisory board member, and speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis. and OM Pharma. All other authors state no competing interests.