Running Head: Practices Surrounding COPD and Desaturation

Funding Support: This study was funded as a pilot grant from the American Lung Association.

Date of Acceptance: July 9, 2023 | Published Online Date: July 11, 2023

Abbreviations: ACRCs=Airways Clinical Research Centers; ATS=American Thoracic Society; CAT=COPD Assessment Test; CMS=Centers for Medicare and Medicaid; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COREQ=Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research; DLCO=diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; LOTT=Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial; PIs=principal investigators; PFT=pulmonary function test

Citation: Zaeh SE, Case M, Au DH, et al. Clinical practices surrounding the prescription of home oxygen in patients with COPD and desaturation. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2023; 10(4): 343-354. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2023.0402

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (236KB)

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects more than 16 million Americans and is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States.1 Patients with COPD are frequently prescribed chronic home oxygen therapy, with more than 1 million Medicare recipients receiving oxygen therapy at an annual cost of $2 billion.2 Two landmark trials performed in the 1970s established the survival benefit of oxygen therapy for patients with severe resting hypoxemia.2,3 For some time afterward, the utility of oxygen therapy for other populations, such as patients with isolated exertional desaturation, remained uncertain. Nevertheless, the potential benefits of oxygen therapy were extrapolated to this patient population, and prescribing oxygen therapy for patients with isolated exertional desaturation became accepted practice, in part due to reimbursement coverage by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS).4

The benefits of using home oxygen for isolated exertional desaturation are unclear, with a recent report suggesting inconsistent effects on patient-reported outcomes, but with the potential for home oxygen to increase exercise capacity and reduce breathlessness during exercise testing in a laboratory setting.5 In addition, the Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial (LOTT) study included 319 patients with COPD and isolated exertional desaturation; in this population, time to death or first hospitalization was not improved by home oxygen compared to usual care alone.6 Secondary outcomes, including quality of life and 6-minute walk distance, were also not improved.6 Oxygen therapy is also associated with harms. Home oxygen use can: (1) restrict social and physical activities, (2) increase the risk of falls from tripping over equipment, (3) cause burns or house fires, (4) cause physical discomfort or epistaxis, and psychological factors such as stigma and embarrassment, and (5) create unnecessary expense.7 Despite the possible risks of home oxygen use and recent results from LOTT, oxygen therapy continues to be widely prescribed to patients with isolated exertional desaturation, perhaps in part because CMS continues to cover chronic home oxygen therapy for this indication.

Both the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2020 home oxygen guidelines and the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2023 report emphasize the importance of shared decision-making and the consideration of individual patient factors when evaluating the need for oxygen in patients with COPD who desaturate only with exertion, with ATS guidelines providing a conditional recommendation for ambulatory oxygen and the GOLD report recommending against routine prescription for ambulatory oxygen.5,8

Prior literature regarding clinical practices surrounding oxygen prescription for patients with COPD has discussed barriers to adequate oxygen services, including: (1) inadequate evaluation and documentation of oxygen needs,9 (2) challenges in interactions with durable medical equipment companies,10,11 (3) lack of effective patient instruction regarding oxygen use,11 (4) unclear patient adherence to oxygen,12 and (5) lack of deimplementation of oxygen following hospital discharge.13 There has been a call for clinicians to improve the patient experience with oxygen by better understanding prescription requirements, ensuring patient equipment meets patient needs, and providing patients with better education regarding oxygen use.10

Within clinical practices surrounding oxygen prescriptions for patients with COPD, the drivers of clinician prescription patterns of chronic home oxygen therapy for patients with COPD remain poorly understood. In this study, we conducted semi-structured interviews with clinicians to explore their thought processes and practice patterns surrounding the prescription of chronic home oxygen therapy for COPD patients. Improved understanding of these factors has the potential to inform strategies to promote evidence-based use of oxygen therapy for patients with COPD.

Methods

Participants

Physician (both attendings and pulmonary and critical care fellows) and dedicated pulmonary nurse practitioner participants were recruited from the American Lung Association Airways Clinical Research Centers (ACRCs) network using convenience sampling, with assistance from the principal investigators (PIs) of ACRC clinical sites. To meet inclusion criteria for the study, participants were required to provide clinical care for patients with COPD.

Procedures

The University of Illinois Chicago (2021-0141), Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (00280675), and Yale School of Medicine (2000031384) institutional review boards approved this protocol. The project was introduced through ACRC group meetings and emails sent to the PIs of ACRC clinical sites. Clinicians interested in participating in the study were asked to contact research staff who scheduled them for an interview. At the time of the scheduled interview, clinician participants first completed an oral informed consent, with the opportunity to have questions answered prior to participation in the study.

Semi-structured videoconference interviews were conducted by a single researcher (SZ), a pulmonary and critical care medicine fellow with expertise in qualitative interviewing. The interviewer had no prior direct relationship with participants. Only the interviewer and participant were present during videoconference interviews. Following the interview, participant demographic data were collected. Participants were offered a $50 gift card as compensation for completing the interview. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by a professional medical transcriptionist. Transcripts were deidentified prior to being analyzed.

Interview Guide

The interview guide was developed by the study authors, including pulmonologists, a clinical psychologist, and patients with COPD (Supplement 1 in the online supplement). The guide included open-ended questions regarding clinician practices surrounding prescription of oxygen for patients with COPD, including the use of shared decision-making. Prior to initiation of the study, the interview guide was piloted with 2 clinicians who care for patients with COPD and modified for clarity based on feedback.

Analysis

A thematic analysis approach was used to analyze qualitative interview data. Transcripts were analyzed using NVivo 12.0 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Australia). Two investigators (SZ and ME) read transcripts and inductively developed a codebook (Supplement 2 in the online supplement). After creation of the codebook, investigator SZ performed line-by-line coding of all transcripts, iteratively updating the codebook as needed. An independent investigator, MC, then used the codebook to double code each interview. Investigators SZ and MC met with the senior qualitative investigator, ME, to resolve discrepancies in coding and discuss any changes made to the codebook. Coding comparison between SZ and MC was calculated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient and through calculating a percentage agreement. It was determined that thematic saturation occurred when no new codes emerged for at least 3 interviews.

Codes were organized into themes using content analysis to create conceptual themes related to clinician practices surrounding the prescription of oxygen for patients with COPD.14 Clinician participants did not formally provide feedback on study findings. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) was used to guide comprehensive reporting of interviews (Supplement 3 in the online supplement).15

Results

Eleven PIs from the ACRC who expressed interest in the study were approached regarding participation in the study, with 9 PIs agreeing to participate in the study and recruit additional colleagues. Ultimately, 19 clinicians expressed interest in participating in the study and 18 were consented and completed the interviews (15 physicians and 3 pulmonary nurse practitioners). Among the 15 physicians, 3 were fellows who had completed at least their first year of pulmonary fellowship training. Most participants were men (N=12, 66%) and between the ages of 31 and 50 (N=11, 61%). Participants were closely divided in their years of clinical practice with 6 (N=33%) in practice from 5–10years, 7 (N=39%) in practice for 10–15 years, and 5 (N=28%) in practice from 15–20 years. Ten participants reported they spent 50% or less of their time in clinical practice and 8 participants said they spent over 50% of their time in clinical practice. The mean length of time of the interviews was 34.4 minutes with a standard deviation of 6.05 minutes.

The kappa for inter-rater reliability of all codes was K=0.78, indicating substantial agreement. The percentage of agreement was calculated to be 98.7%.

Factors Impacting Clinician Decision-Making

Clinicians expressed several factors which impacted their decision-making surrounding the prescription of home oxygen for patients with COPD. Specifically, clinicians reported that their decisions were impacted by their assessment of research evidence, clinical experience, and patient preferences regarding the use of oxygen (Figure 1).

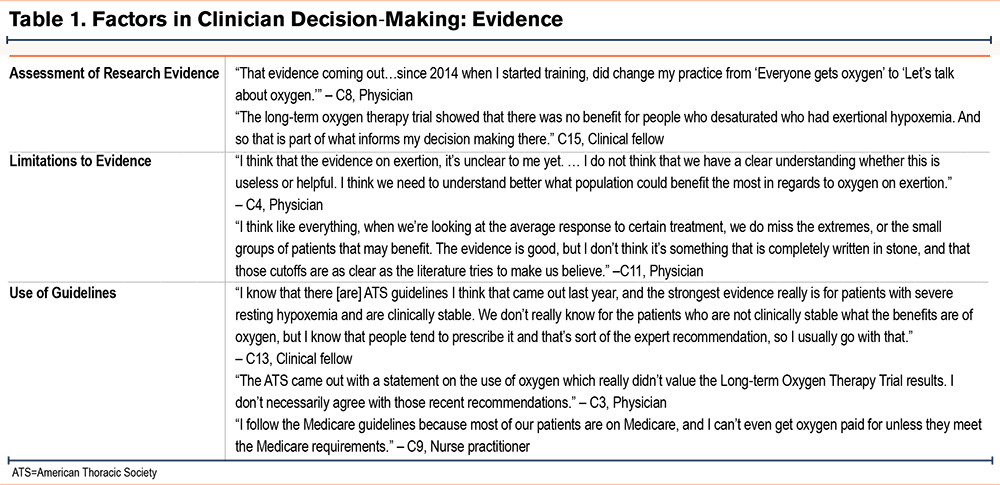

Evidence

Several clinicians acknowledged that the “evidence base is quite thin” surrounding home oxygen use in patients with COPD, but most noted that the available prior evidence supported prescribing oxygen for patients with COPD who have resting hypoxemia (Table 1). One physician explained that prior to LOTT:

“The recommendation to use [oxygen] that was also with exercise was somewhat of an extrapolation.”

The LOTT study results led to variability of clinician opinion regarding whether oxygen should be prescribed for patients with COPD who desaturate only with exertion. Some clinicians expressed the strength of evidence supporting the lack of benefit of oxygen use for this patient population. As one physician said:

“The LOTT trial that came out a few years ago is pretty good evidence and a well-designed trial, and so I think it’s evidence that is worthy of adopting into clinical practice.”

Another physician stated:

“Looking at the exertional hypoxemia group, I don’t think the data there is very convincing that there’s a benefit in that population [of oxygen use]. I don’t know that the field has caught up with that.”

Other clinicians recognized that there may be limitations in using a randomized control trial such as LOTT to determine if patients with COPD and desaturation only with exertion should use home oxygen. As one physician said:

“I think this is really an area that one study doesn’t cover...it won’t apply to every single patient, right? Of course, when you do those trials, there are selected populations, probably different from people who we see…it is a case-by-case scenario.”

Additionally, some clinicians acknowledged that their prior clinical experience differed from the results of LOTT, leading them to prescribe home oxygen for patients with COPD who desaturate only with exertion. As one nurse practitioner said:

“Despite the LOTT trial, I have to say that I am very pro-oxygen. I get the primary outcomes didn’t necessarily support its use, but I do find for the majority of patients they feel better, they can do more with supplemental oxygen if they have it with activity, and if they’re using it with sleep, they feel better in the morning.”

Clinicians reported that they used ATS and CMS coverage decisions to help guide their prescription of home oxygen for patients with COPD. Regarding the ATS guidelines, a nurse practitioner explained:

“There’s a high recommendation for prescribing oxygen, but it’s less clear if it’s with activity. That is where it goes case by case.”

Some physicians explained that they use CMS coverage decisions most frequently regarding the prescription of home oxygen because “otherwise we can’t get it covered.”

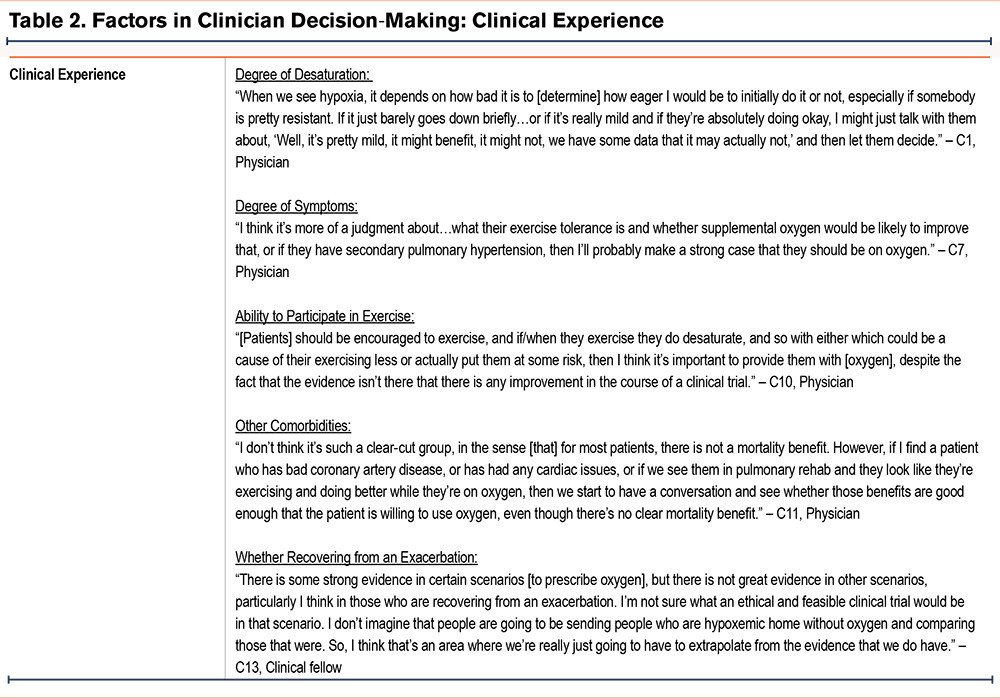

Clinical Experience

Clinicians considered a number of factors based on their clinical experience that influenced their decision to prescribe home oxygen for patients, including: (1) degree of desaturation, (2) degree of patient symptoms, (3) improvement in patient tolerance to exercise with oxygen, (4) whether the patient was recovering from an exacerbation, and (5) the patient’s additional comorbidities (i.e., if they had underlying pulmonary hypertension) (Table 2). As one physician stated:

“If they’re not symptomatic, I usually don’t get excited about it...knowing the fact that this large study from the NIH did not show any benefit. If they’re symptomatic, it’s different. I’m very tempted to prescribe it and try to justify it to the insurance company.”

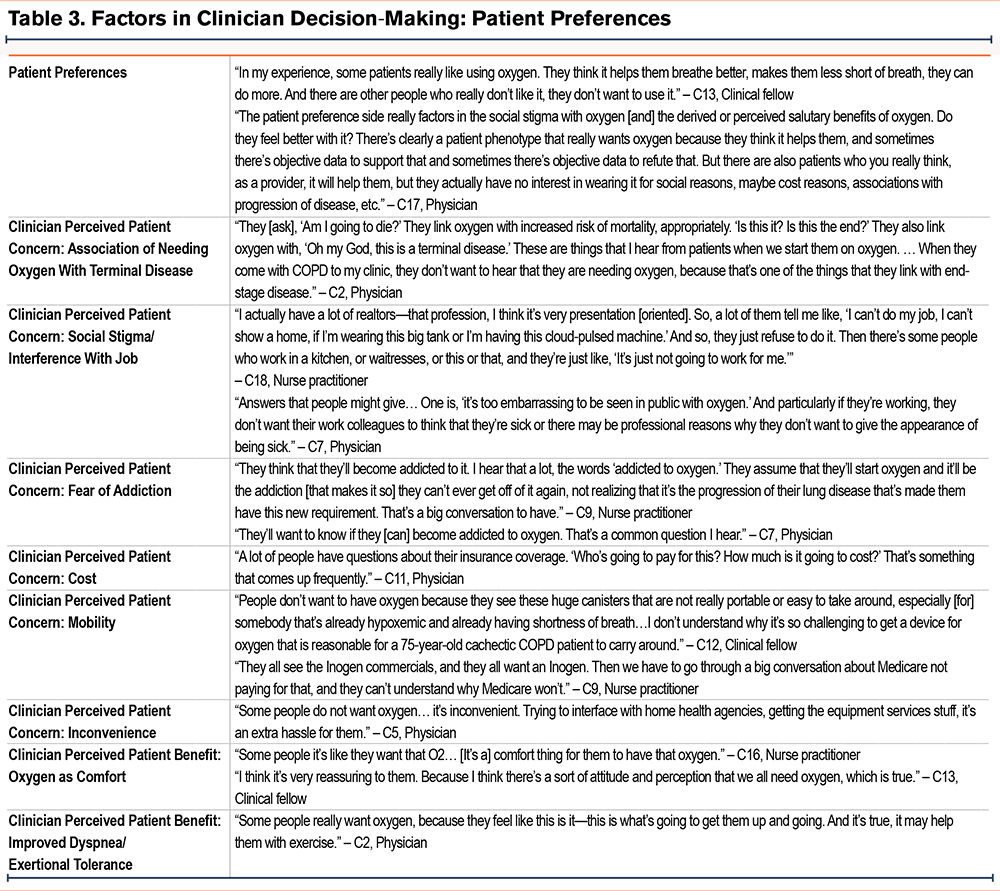

Patient Preferences

Patient preferences played a large role in clinician decision-making regarding prescription of home oxygen use for patients with COPD (Table 3). Clinicians described a spectrum of patient preferences regarding oxygen, from some patients being interested in oxygen use and others refusing oxygen. As one physician said:

“I think the range is from, ‘by all means, if it’ll help me walk a little bit farther and do a little bit more, I want to get it as soon as possible’ to, ‘there’s no way I would ever use supplemental oxygen, no matter what.’ And then there is everything in-between.”

Some clinicians reported feeling that, “I don’t really need to convince patients; it is either one way or the other” regarding oxygen use as patients had an opinion regarding how they wished to proceed. Other clinicians described working with patients who insisted on oxygen use to try to “craft a plan in terms of, ‘Ok, we’re going to use it, but we’d like to see if this actually is benefiting you in some way or manner.’”

Clinicians reported several patient concerns related to home oxygen use, including association of the need for oxygen with terminal disease, social stigma and interference with one’s job, fear of addiction, cost, and mobility. As one nurse practitioner said:

“It’s something that is a marker of disease severity for a lot of people. They always have somebody in mind that they know who was on oxygen. And maybe not long before they died, they started oxygen.”

A physician described the stigma of oxygen use:

“I think in COPD in particular, there’s unfortunately some stigma because of the association with tobacco use and even some kind of self-flagellation for you know, having been a smoker and having done this to myself...we all do things to ourselves sometimes that are not the best thing for our physical or mental health.”

Clinicians also described the benefits that patients perceive about oxygen use; specifically, oxygen providing comfort and leading to improved dyspnea or exertional tolerance. As one nurse practitioner said:

“I think people maybe like the thought of a safety net.”

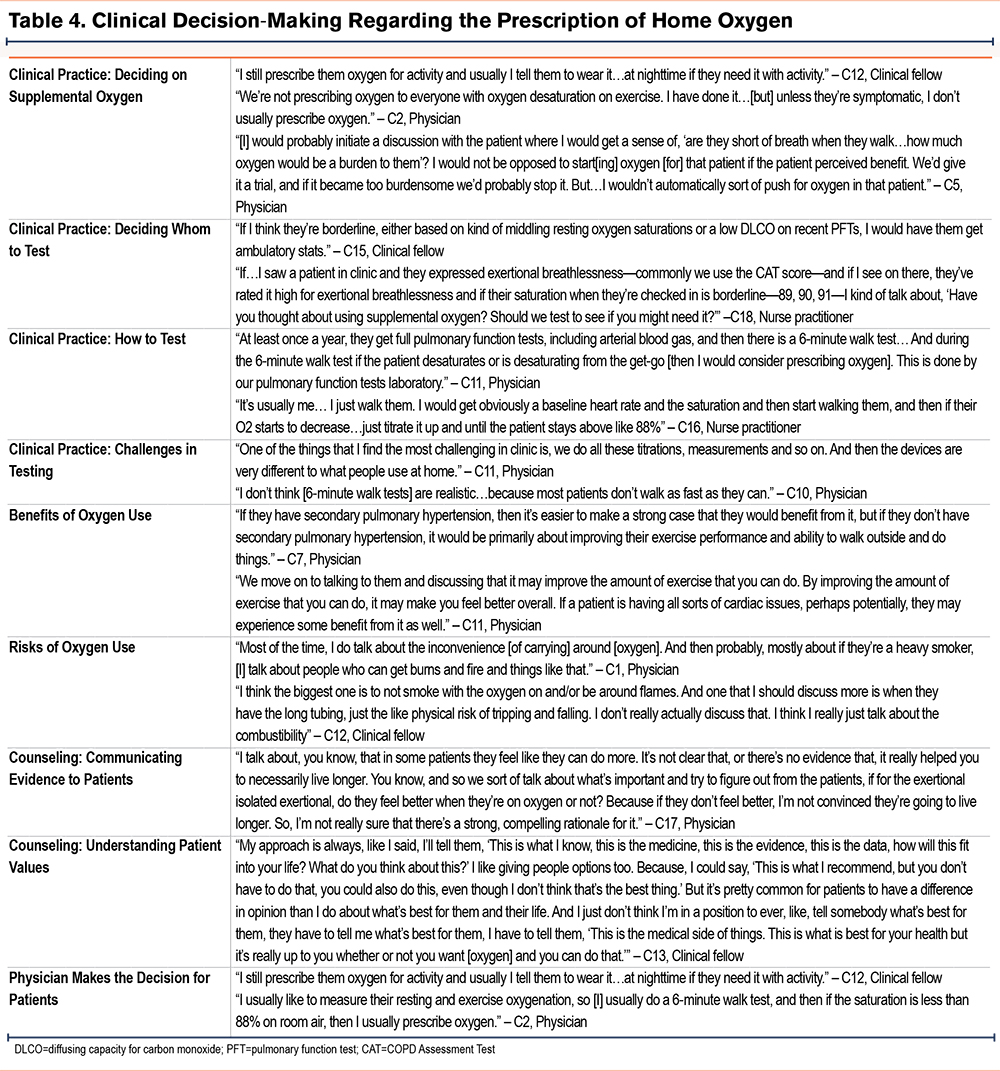

Clinical Decision-Making Regarding the Prescription of Home Oxygen

There were a range of clinical practices described by clinicians surrounding the decision to prescribe home oxygen for patients with COPD, with some clinicians offering oxygen to all patients who qualify and others trying to avoid oxygen use if possible (Table 4). As one nurse practitioner stated:

“I offer it to pretty much everybody. I don’t order it if they’re the ones that say they don’t want it.”

One clinical fellow reported:

“We know that in some scenarios, over-oxygenating people can potentially lead to worse outcomes, and so I tend to favor not using it.”

Clinicians described the process of prescribing home oxygen for patients with COPD, starting with whom and how to test. Most clinicians emphasized the core components of shared decision-making with patients, including discussing the benefits and risks regarding oxygen use, communicating evidence to patients, and aiming to understand patient goals and preferences for treatment. Information included within these conversations varied and was not based on a shared decision-making tool. Some clinicians acknowledged that they make the decision themselves regarding home oxygen use for patients, rather than having a shared decision-making conversation.

Clinical Practice: Whom and How to Test and Challenges With Testing

Clinicians described variable practices in deciding whom to test among patients with COPD for home oxygen needs. Some clinicians tested every patient with COPD for resting and ambulatory desaturation. Others reported that the patient’s clinical status or pulmonary function testing results determined if the patient should be tested for ambulatory desaturation. As one nurse practitioner said:

“If I have a suspicion that patients are desaturating with activity, then I order the walk test, or if they complain of excess dyspnea with exertion, I’ll order the walk test.”

Finally, some clinicians described having a conversation with patients to determine patient preference for testing prior to ordering an ambulatory saturation. As one physician said:

“I normally talk with them... ‘Well, your oxygen saturation is a little bit low...and it may actually go down to some level that you might need oxygen, so would you like to be tested?’ Some people [say]... ‘I’m not going to wear it,’ so we don’t do it.”

Clinical practices regarding how to perform testing ranged from clinicians performing walk testing on their own in the clinic, to obtaining formal 6-minute walk testing with pulmonary function testing and an annual arterial blood gas test through the pulmonary function testing laboratory.

Clinicians acknowledged there were challenges in testing patients for home oxygen needs. As one physician said:

“When somebody dips below 88%, they are immediately put on oxygen. It’s not a true walk test to determine a nadir saturation.”

Clinicians also reported that the devices patients use at home are often different than those used for home oxygen testing in clinics.

Clinicians discussed the benefits of oxygen use with patients with COPD including possible improvement in exercise tolerance and prevention of complications for specific patients (i.e., those who desaturate with rest or underlying pulmonary hypertension). One nurse practitioner said she counsels patients by saying:

“Oxygen may make it easier to do your day-to-day activities…you may be able to go further and feel better with supplemental oxygen.”

Some clinicians stated that discussion of oxygen use benefits with patients can be challenging because, “…it’s hard to say, ‘well, you’ll feel better,’ because they don’t necessary feel better.”

Clinicians discussed risks of oxygen use with patients, including cost, inconvenience, impaired mobility, and the risk of fire and burns if the patient continues to smoke while using oxygen. As one physician said:

“The big three that I talk about are costs, tripping, and burns. Cost is real – patients often, especially those who want to remain mobile, end up having to pay out of pocket for a portable oxygen concentrator. We talk about the tripping hazard, especially those who are in the house with longer chords. And then, unfortunately, many of my patients continue to smoke despite having chronic lung disease.”

Counseling: Communicating Evidence and Understanding Patient Values

Some clinicians described communicating evidence to patients to help them make an informed decision regarding home oxygen use. Notably, no clinicians reported using a shared decision-making tool to assist with this conversation. One physician reported that they:

“…reviewed previous studies looking at the treatment of COPD-associated hypoxemia [with patients]. And that there is no sort of proven long-term benefits for using oxygen only with exertion.”

Several clinicians emphasized the importance of understanding what is important to patients in helping them determine whether to pursue home oxygen therapy. As a physician said:

“The purpose of us having this consultation is to try to help you achieve the goals you have for yourself. If your goal is to be able to go out and play with your dog, or take your kids to the zoo, or just to do your grocery shopping without help...we’re going to try to help you achieve that goal. And if oxygen is part of that plan, then great. And if it’s not, or if you really don’t want it, let’s talk about the reasons that you have for not wanting to do this.”

One clinical fellow did explain:

“It makes it easier when there’s not a clear best opinion in that whatever they’re most comfortable with, then it’s fine to support them doing.”

Finally, some clinicians acknowledged that they primarily made the decision for patients regarding home oxygen use, and that there could be improvement to their shared decision-making conversation with the patient. As one physician said:

“It’s a shared decision. But when we prescribe oxygen, we often don’t do that. It’s a one-way highway. We just tell them, ‘Ok, here you go, this is what you need.’”

Discussion

We aimed to investigate clinician practice patterns surrounding the prescription of home oxygen for patients with COPD. Our results suggest there are several factors which contribute to a clinician’s decision to prescribe home oxygen for patients with COPD, including research evidence, clinical experience, and patient preferences regarding oxygen use. These factors influenced clinical decision-making for clinicians differently, with some clinicians offering oxygen to most patients, and others trying to avoid prescribing home oxygen if possible. Most clinicians described a shared decision-making process for prescribing home oxygen for patients, including discussion of risks and benefits and developing an understanding of patient preferences and values. Information included within these shared decision-making conversations was variable and not based on a structured shared decision-making tool.

This study contributes to the literature by developing a better understanding of the approach clinicians use when deciding whether to prescribe home oxygen for patients with COPD. The themes highlighted by clinicians within our study as being influential to their decision-making – research evidence, clinical experience, and patient preference – align well with the framework of evidence-based medicine. The practice of evidence-based medicine involves integrating individual clinical expertise, which incorporates patient rights and preferences regarding care, with the best available external clinical evidence.16

There was variability in clinician practices in the decision to prescribe home oxygen for patients with COPD. We suspect this variability largely reflects clinicians weighing patient preferences highly within their decision-making process, as a form of patient-centered care. Notably, this variability is reflective of the uncertainty that exists in clinical practice guidelines, with ATS guidelines providing a conditional recommendation for ambulatory oxygen and the GOLD guidelines recommending against routine prescription for ambulatory oxygen.5,8 There was also variability in whom and how clinicians performed testing to assess for the need for home oxygen, which we suspect was largely driven by a lack of high-quality evidence in this area.

Additionally, clinicians within our study highlighted the need for shared decision-making prior to prescribing home oxygen for patients with COPD and isolated exertional desaturation, in concordance with the 2020 ATS guidelines emphasizing the need for shared decision-making with this patient group.5 Shared decision-making is “an approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of making decisions, and where patients are supported to consider options, to achieve informed preferences.”17 Within shared decision-making, patients are encouraged to consider the likely benefits and harms of screening, treatment, or management options to select the best course of action.18 The 2023 GOLD strategy report, released after the completion of these interviews, similarly recommends taking individual patient factors into account when evaluating a patient’s need for supplemental oxygen with COPD patients who desaturate only with exertion.8

Shared decision-making is considered the pinnacle of patient-centered care19 and an ethical imperative in clinical medicine today.20 It has been shown to improve the quality of patient-physician communication, improve the overall satisfaction of patients and physicians, and increase adherence to the treatment regimen selected.21 Clinical decision support tools or decision aids can play an important role in shared decision-making by helping to provide evidence-based information to patients and helping patients clarify their values.22 Patient decision aids have been shown to increase patient involvement, improve the accuracy of participants’ perceptions of their risks, decrease decisional conflict, and lead to value-based care decisions.23

Shared decision-making has been used in several clinical scenarios related to COPD, including inhaler choice,24 referral to pulmonary rehabilitation,25 and the decision to perform a lung cancer screening. A recent systematic review suggests that shared decision-making tools for lung cancer screenings may improve knowledge and reduce decisional conflict, while being acceptable to patients and providers.26 However, to our knowledge, there are no published shared decision-making tools that could inform discussions between patients and their providers about the use of home oxygen. Development of a shared decision-making tool to help support patients and physicians regarding home oxygen use may be the next step to improve shared decision-making regarding home oxygen in patients with COPD.

There were limitations to the study. The study included a small number of participants, but thematic saturation was reached with no new codes emerging for at least 3 interviews. Potential sampling bias may exist, as clinicians who were enrolled were affiliated with an obstructive lung disease clinical trials network, and were primarily academic clinicians, with half of participants spending 25% or less of their time in clinical practice. The results of the study might be different in the setting of community pulmonologists, who spend a larger percentage of their time seeing patients clinically. Additionally, most of the clinicians interviewed for this study were pulmonary physicians. Thus, the sample population may limit generalizability of these findings to other populations caring for patients with COPD, including non-physician practitioners, primary care providers, and non-academic clinicians. Finally, this study focused on clinician factors regarding home oxygen use but does not include the perspectives of patients regarding home oxygen use, which have been described previously.11

In conclusion, a number of factors including research evidence, clinical experience, and patient preference may impact clinicians in deciding whether or not to prescribe home oxygen for patients with COPD. A shared decision-making tool could facilitate discussions between providers and patients about the home use of oxygen.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: SZ, DA, MD, KD, JD, LF, JK, JS, AW, and ME were involved in the conception and/or design of the study. SZ was involved in the acquisition of the data. SZ, MC, LF, JK, and ME were involved in data analysis and interpretation. All authors were involved in writing the article or had substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission.

Declaration of Interest

This study was funded as a pilot grant from the American Lung Association. JK and ME received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of this study. LCF received a stipend as associate editor at the Annals of the American Thoracic Society. LCF also received honorariums from the National Committee for Quality Assurance to develop a COPD curriculum for primary care, the American Thoracic Society for participation on an expert panel for a Council of Medical Specialty Societies and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine initiative, and the Society of Hospital Medicine for work on a study focused on reducing hospital readmission after COPD exacerbations. LCF also received funding from the Veterans Administration, National Institutes of Health, and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute for research outside the scope of this work. DHA received remuneration from the American Thoracic Society for editorial work at the Annals of the American Thoracic Society,and from Boehringer Ingelheim for creation of video materials on adherence of medication in COPD. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.