Running Head: Sexual Orientation Respiratory Health Disparities

Funding Support: No funding for this project.

Date of Acceptance: April 1, 2024 | Publication Online Date: April 3, 2024

Abbreviations: BRFSS=Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OR=odds ratio

Citation: Ferriter KP, Parent MC, Britton M. Sexual orientation health disparities in chronic respiratory disorders. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2024; 11(3): 307-310. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2023.0467

Introduction

The prevalence of cigarette smoking (hereafter, smoking) among sexual minority (i.e., lesbian, gay, and bisexual) individuals is 30%−38%, compared to 17%−21% among heterosexual individuals.1 Smoking among sexual minorities is elevated, in part, in response to minority stress (i.e., experiences of discrimination and harassment as well as internalized stigma such as internalized homophobia).2,3 The differences in smoking prevalence are also influenced by cigarette advertising campaigns that target marketing toward sexual minorities.4,5

Smoking is linked with an increased risk of developing chronic respiratory disorders such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (2.9x risk) including emphysema (4.5x risk) and chronic bronchitis (2.7x risk).6 One prior study demonstrated that sexual minority individuals have higher rates of obstructive airway disorders,7 though that study did not examine the contribution of smoking as a cause of those disorders and used data from participants aged 33-43, which is below the age at which many smoking-related respiratory disorders develop.8 Other work demonstrated a link between smoking and asthma disparities for sexual minority individuals.9 Though this work included a wider age range of participants it did not assess respiratory conditions that may emerge later in life such as COPD, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis. Another study used data from national surveys from 2014−2020 to examine broad disparities in chronic physical health among sexual minority individuals; this study found that sexual minority individuals had 30% greater odds of having a chronic respiratory disorder compared to heterosexual individuals.10 This study, however, did not examine the contribution of smoking to respiratory disorders among sexual minority individuals and also included individuals as young as 18, thereby, possibly underestimating the burden of COPD among sexual minority individuals by including individuals well below the typical age for presenting with chronic respiratory disorders. There is a need to better understand how smoking may contribute to disparities in chronic respiratory disorders, especially among older sexual minority individuals.

The objective of the current study was: (1) to examine disparities in chronic respiratory disorders for sexual minority individuals, (2) to examine the extent to which smoking mediates the link between sexual minority identity and chronic respiratory disorders.

Methods

Data from the 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) were used in the study. The analytic sample included 161,741 individuals (3.6% identified as sexual minorities) aged 45 and older. Only data from those 45 and older were used, consistent with prior work on smoking and chronic respiratory disorders using BRFSS data,11 to capture individuals in the age range at risk for chronic respiratory disorders. Smoking was measured by assessing whether participants had smoked 100 cigarettes or more in their life. The primary outcome was self-reported diagnosis of “COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis” (assessed as a single item in the BRFSS). Cross-tabulations were conducted in SPSS version 28 (IBM, Armonk, New York) and mediation analyses were conducted using Mplus version 8.7 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, California) with appropriate sample weighting for the complex survey design. Sexual minority status (coded as 0=heterosexual, 1=sexual minority) was entered as the independent variable. Smoking (coded as 0=responded no to smoking 100 or more cigarettes in their life, 1=responded yes to smoking 100 or more cigarettes in their life) was entered as a mediator. Self-reported COPD (coded as 0=no reported diagnosis, 1=reported diagnosis) was entered as the dependent variable. Mediation was examined by looking at indirect effects, calculated using 5000 bootstrapped samples. The analyses used deidentified, publicly available data, which is considered nonhuman participant research under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office, and thus, does not require institutional review board review.

Results

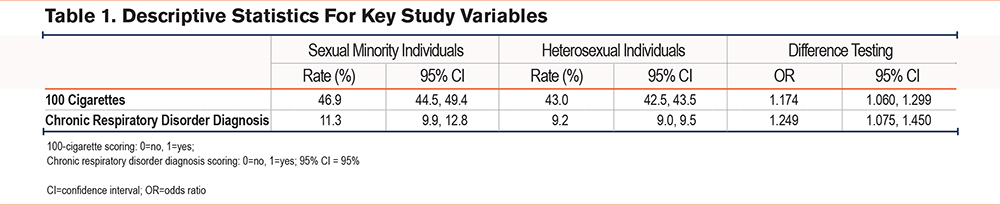

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for key study variables. Corroborating prior research, smoking was 1.17 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06, 1.30) times more common among sexual minority individuals compared to heterosexual individuals. The prevalence of chronic respiratory disorders was 1.25 (95% CI 1.08, 1.45) times higher among sexual minority individuals compared to heterosexual individuals.

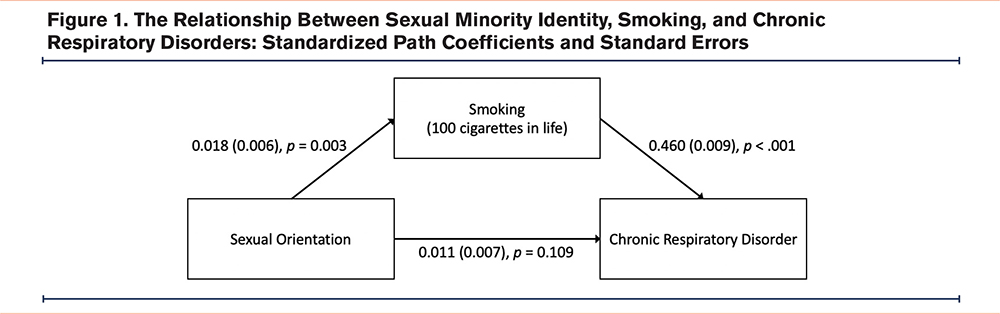

We examined the relationship between sexual minority identity, smoking, and chronic respiratory disorders using mediation analyses. Standardized path coefficients and standard errors are displayed in Figure 1. Indirect effects were examined using 5000 bootstrapped samples; the indirect path from sexual minority identity to chronic respiratory disorder via smoking was significant, B=0.008, SE=0.003, p=.003; 95% CI 0.003, 0.014, and the model R2 for chronic respiratory disorders was 0.212. Thus, the model supported smoking as a mediator of the relationship between sexual minority identity and chronic respiratory disorders. The proportion of the relationship between sexual orientation identity and chronic respiratory disorders that was associated with smoking (calculated as the indirect effect over the total effect) was .733, meaning that smoking was a substantial contributor to the observed disparities in chronic respiratory disorders. Thus, the results indicated that the disparities in chronic respiratory disorders among sexual minority individuals were linked, in part, to elevated rates of smoking among that population.

Of note, the present analyses focused on individuals 45 and older. But, using the same BFRSS data and examining only those under 45, smoking was still elevated among sexual minority individuals compared to heterosexuals, odds ratio=1.233, (95% CI 1.118, 1.359). Thus, the observed disparities in chronic respiratory disorders by sexual orientation are likely to persist into future generations of patients.

Discussion

In this study, using data from a large national data set, sexual minority individuals demonstrated elevated rates of smoking and chronic respiratory disorders. Consistent with a body of past research,1,2,10 sexual minority individuals in the sample demonstrated elevated rates of smoking and chronic respiratory disorders compared to heterosexual individuals. The mediation analysis indicated that the relationship between sexual identity and chronic respiratory disorders was linked, at least partially, to elevated rates of smoking. These findings indicate that disparities in smoking among sexual minority individuals may contribute to disparities in chronic respiratory disorders.

Pulmonologists, primary care providers, and other health professionals treating respiratory illness are likely to encounter sexual minority patients. Therefore, the adoption of training and treatment approaches by physicians that both welcome and affirm sexual minority individuals is crucial to facilitate patient uptake and retention to provide optimal care and decrease the burden of chronic respiratory disorders.12,13

The results of the present study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. We used data from the BRFSS, and thus, the assessment of chronic respiratory disorders was limited to the single self-report item used in the BRFSS. This study used cross-sectional data, and thus, we were unable to assess onset or progression of chronic respiratory disorders over time. This study focused on smoking as a contributor to the development of COPD. COPD, and other health conditions, may also be influenced by stigma as well as by other social determinants of health including those for which sexual minority individuals face disparities, such as housing, employment, or exposure to environmental toxins.14-16 Future work may address these social determinants of environmental risks as contributors to COPD among sexual minority individuals.

In conclusion, the sexual orientation disparities presented in this study have care implications for sexual minority individuals that should be considered by physicians treating respiratory illness and those addressing smoking in their practice.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: MP had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects. KF and MP completed the analyses. KF and MB contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Declaration of Interests

None of the authors have any conflicts to declare.