Running Head: Meaning in Life for Promoting Wellbeing in COPD

Funding Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K24 HL138150).

Date of Acceptance: April 1, 2024 | Publication Online Date: May 6, 2024

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRQ=Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GAD-2=Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ISEL=Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12; MCID=minimal clinically important difference; MIL=meaning in life; MLQ=Meaning in Life Questionnaire; MLQ-P=presence of meaning; MLQ-S=search for meaning; mMRC=modified Medical Research Council; PHQ-9=Patient Health Questionnaire; SD=standard deviation; SMAS-30=Self-Management Ability Scale

Citation: Batzlaff C, Roy M, Hoult J, Benzo R. Meaning in life: a novel factor for promoting well-being in COPD. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2024; 11(4): 341-349. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2023.0476

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (183KB)

A portion of this work was presented as an oral presentation at the CHEST 2023 Annual Meeting in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Introduction

Meaning in life (MIL) is defined as “the sense made of, and significance felt regarding, the nature of one’s being and existence.”1

MIL is associated with well-being in healthy populations1 and there is some recent evidence that those who find meaning in life may be better able to cope with medical challenges.2-5 Justifiably, those attempting to process health-related challenges may prioritize defining life’s meaning to better cope.6,7 Prior studies have demonstrated that serious illness confronts one’s perception of life balance – their values, priorities, and future life endeavors. Adaptive thought processes invite complex and uncomfortable questions regarding meaning in life; allowing responses to be flexible and goals to be modified.8

MIL has been studied in various patient populations with chronic conditions, like cancer,9-12 cardiac disease,13-16 and other life-threatening, chronic illnesses.3,5 MIL was related to higher psychological well-being in a sample of individuals living with spinal cord injury.17 Similarly, cancer patients with higher meaning in life reported improved quality of life,18 higher well-being,19 and lower levels of depressive symptoms and fatigue.20

However, there is a knowledge gap in other prevalent conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). COPD is a leading cause of disability21 and has been in the top 10 since 1990. Living with COPD negatively impacts quality of life22-25and further challenges MIL.26

Given the growing importance of personalized support to patients to promote wellness while living with COPD, the inquiry of meaning in life may be significant during patient encounters to foster motivation for better coping.

We aimed to investigate the association of MIL with clinically meaningful outcomes for patients living with COPD in a large and well-characterized cohort.

Our study hypothesis was that the perception of MIL is independently associated with clinically meaningful outcomes for those living with COPD. Deepening our understanding of the association of MIL with outcomes may provide an opportunity to inform the conversations with patients about what is meaningful and worth pursuing, as well as setting goals for lifestyle change in chronic care interventions, like pulmonary rehabilitation, self-management programs, or health coaching.

Methods

Ethical Approval

This was a retrospective analysis using a large database from a randomized-controlled trial that received Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approval on January 11, 2018, IRB#17–009449.

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis using baseline measures (before intervention) from a large cohort with moderate–severe COPD that participated in a home-based pulmonary rehabilitation study. Sites included: Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; and Jacksonville, Florida; and Health Partners, Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria included a clinical diagnosis of COPD (primary inclusion criteria) confirmed by records, age ≥40 years old, a history of a minimum of 10 pack years of smoking, and the ability to communicate in English.

Participants

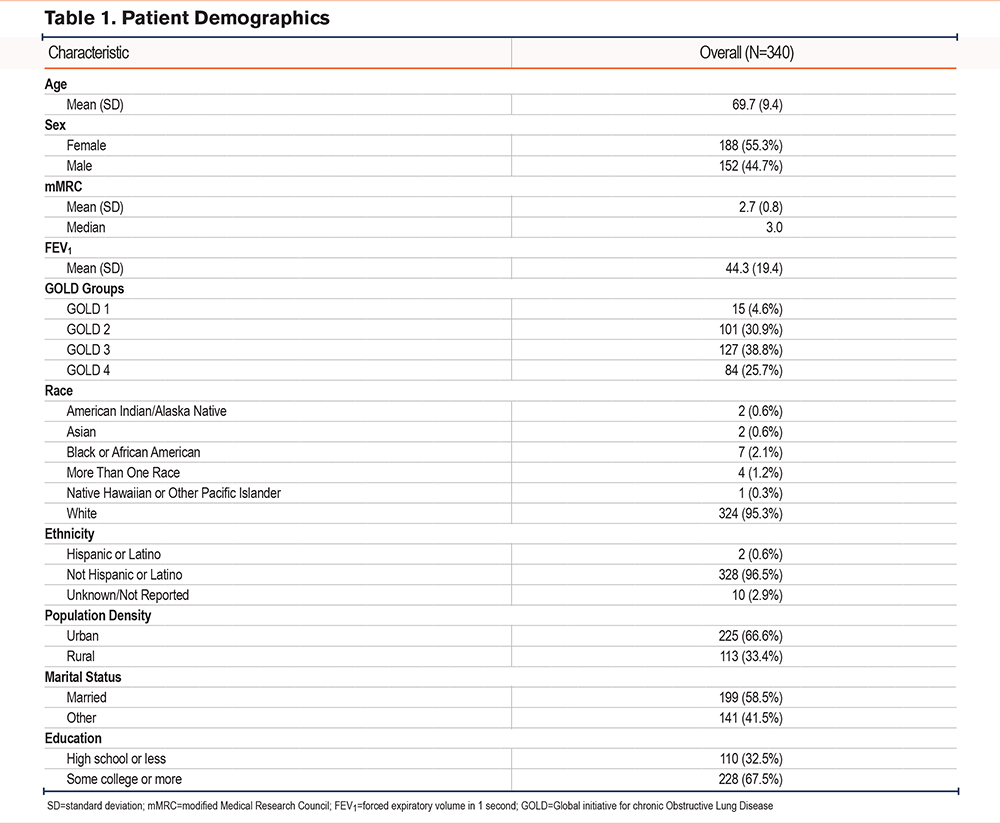

This analysis included 340 participants. Demographics data is displayed in Table 1.

Outcomes

Demographics information, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)27 group were gathered via chart review. To further assess their COPD, health-related quality of life metrics, and activity levels, the following information was collected: modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (ISEL), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item (GAD-2), Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ), Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ), and Self-Management Ability Scale (SMAS-30). Details can be found in the online supplement.

The MLQ is a 10-item tool with 2 separate subscales: the Presence of Meaning (MLQ-P) and the Search for Meaning (MLQ-S). Each subscale captures a different component of human functioning: presence as a tangible outcome versus search as an active and evolving process.1

MLQ-P subscale represents the subjective sense that one’s life is meaningful. It refers to an individual’s understanding of themselves and how they fit into their surrounding environment or community; example “my life has a clear sense of purpose.”

MLQ-S subscale measures the drive, motivation, and intensity towards finding life's purpose; example “I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful.”

Each subscale is measured by 5 items, rated using a 7-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 5 to 35. Higher scores (≥24) are indicative of higher search or presence of meaning. Subscales had Cronbach’s alpha values 0.82–0.87 with one-month test-retest reliability of 0.70 (MLQ-P) and 0.73 (MLQ-S).1

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics. Continuous data are presented as mean (standard deviation) and categorical data are presented as counts (percentages). Comparisons in quality-of-life measures between patients with high versus low MLQ-P and high versus low MLQ-S were made using Wilcoxon signed rank tests. Linear models were generated to determine the association between MLQ-P and MLQ-S with each of the CRQ domains and SMAS-30 total score. These models were adjusted for age, sex, FEV1, ISEL, mMRC, GAD-2 and PHQ-9. Additional models were generated to investigate the association between MLQ-P and MLQ-S with PHQ-9. These models were adjusted for age, sex, FEV1, ISEL, mMRC and GAD-2. Bootstrapping with 1000 replications was conducted on all models to generate robust confidence intervals.28,29 P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant; analysis was completed using R.30

Results

The study population was primarily White, non-Hispanic individuals with the majority of the participants having attended higher education. There was also a slight female predominance and 33% of the population came from rural areas. This demographic data is important to consider in the context of the below results, as they represent specific populations.

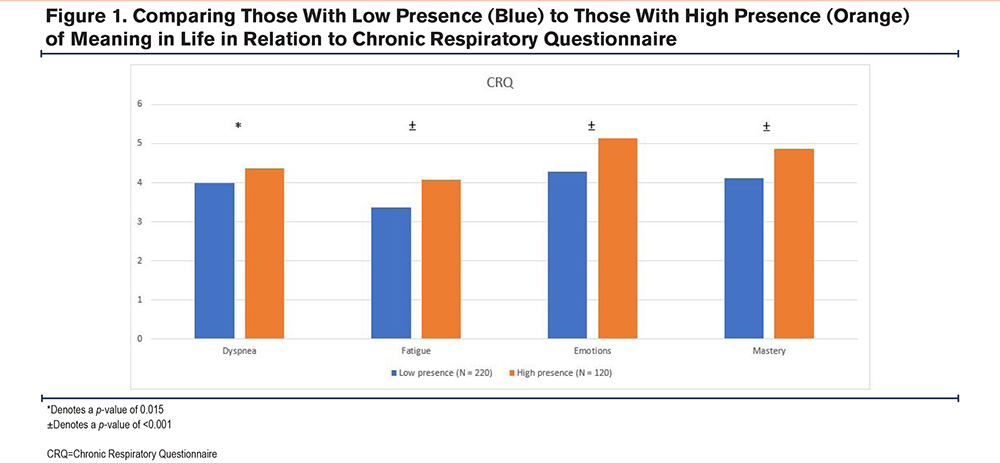

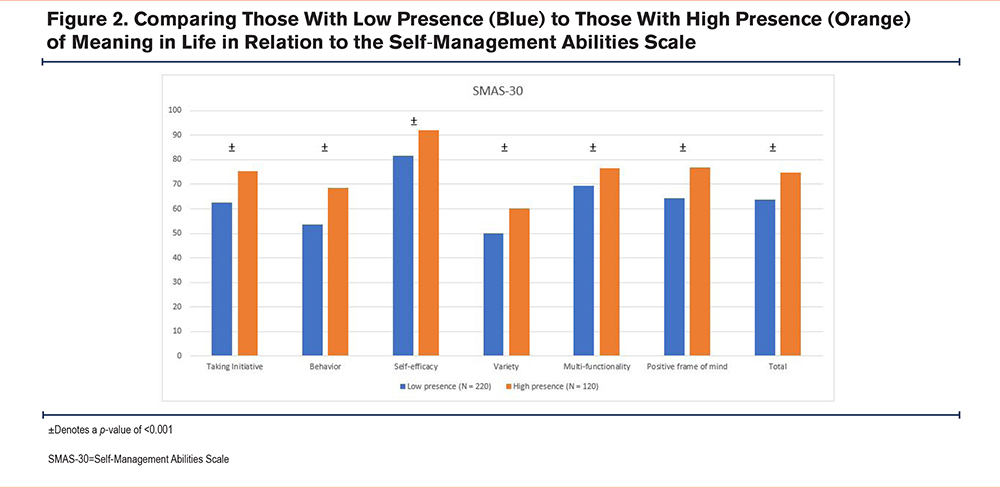

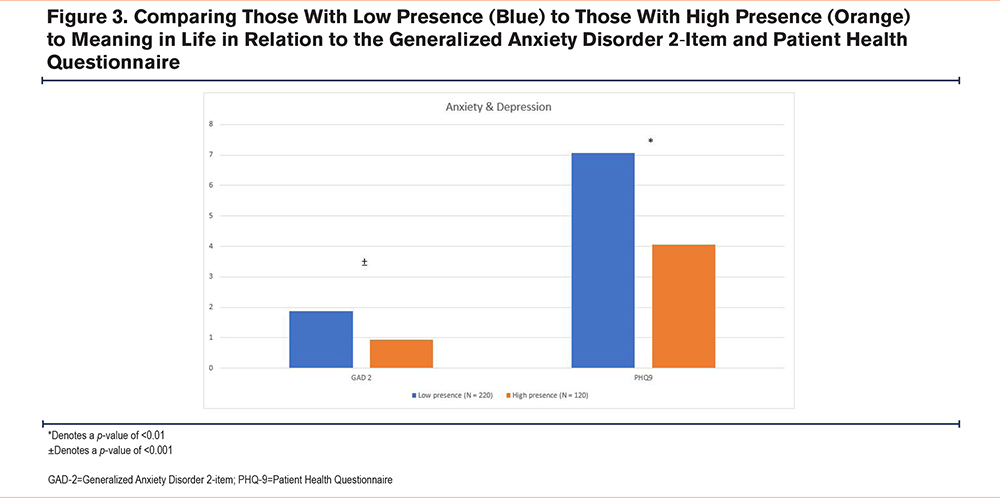

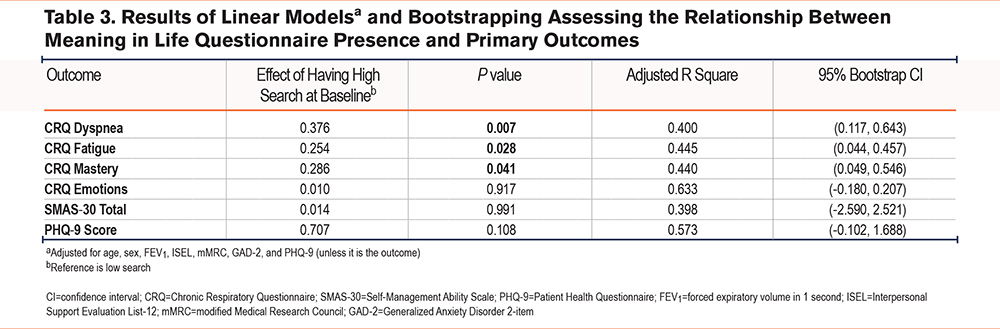

Individuals with high MLQ-P (versus low), have significantly better scores (beyond the minimal clinically important difference) across all CRQ domains: Dyspnea, Fatigue, Emotions, and Mastery (p≤0.02); self-management SMAS-30 (p≤0.001); social support ISEL (p≤0.001); anxiety GAD-2 (p≤0.001); and depression PHQ-9 (p≤0.01) scores (Figure 1-4).

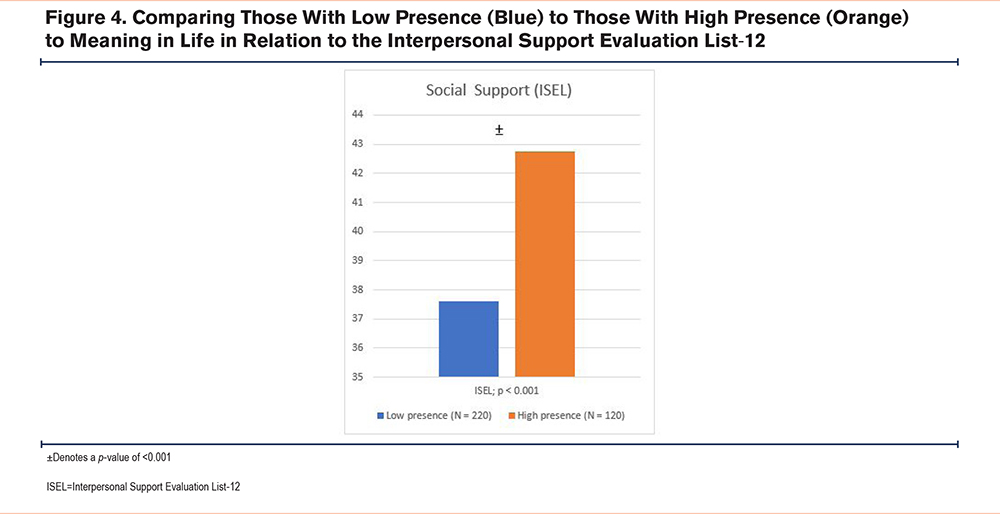

As seen in Table 2 below, MLQ-P was independently associated with higher CRQ scores in the domains of Fatigue (p<0.001) and Emotions (p=0.003), as well as higher total self-management ability scores (p≤0.001).

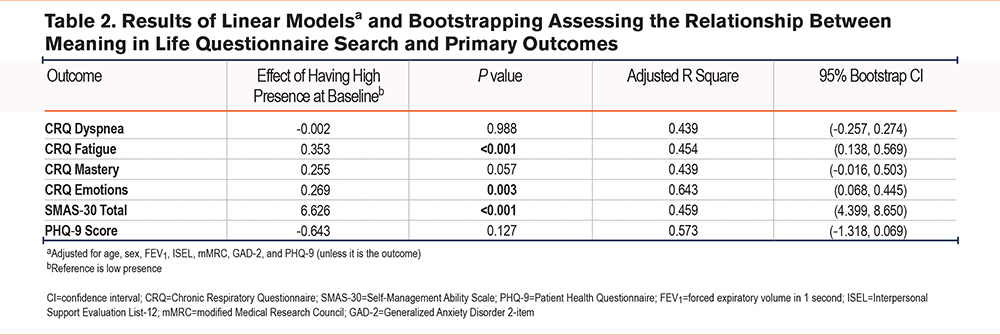

MLQ-S was independently associated with higher CRQ scores in the domains Dyspnea (p=0.007), Fatigue (p=0.028), and Mastery (p=0.041) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study identified significant and independent associations of presence of and search for meaning in life to disease-specific quality of life, self-management abilities, and symptoms of depression in a well-characterized COPD cohort. Our results are novel as there is a scarcity of reports on the value of MIL in COPD. In the literature review, there was only one study identified that investigated meaning in life and self-care agency in the COPD population.31

High Presence of Meaning in Life

We found that those with high presence of MIL perceived better quality of life, better self-management abilities, better social support, and less anxiety and depression. The models adjusting for confounders show that presence (MLQ-P) was independently associated with higher scores in the CRQ domains of Fatigue, Emotions, Mastery, and total self-management ability scores.

Our study confirmed previous findings that meaning in life predicts positive well-being in patients with chronic and/or life-threatening disease.3,7,9,32 Hsieh et al found that presence of meaning in life was a main mediator of depressive symptoms and trait mindfulness.9 Sherman et al identified that high personal meaning is independently associated with lower distress and improved coping in the primary care and cancer populations.7 Health anxiety is also reduced in those with high presence of meaning.2 We could suggest that high presence of meaning in life may provide individuals with emotional resiliency and allows for better coping when faced with adversity.

On review of the cardiac literature, the capacity to find meaning in life after a significant cardiovascular event is associated with lower stress and improved mental health.13 Vos et al suggests a variety of mechanisms to elicit change and focus on the meaning-making,13 including adjustments to life perspective, connecting to fundamental values, building self-worth through hope and optimism, learning to self-regulate, and accepting limitations.

High Search for Meaning in Life

We found that the search for meaning in life (MLQ-S) was an independent predictor of higher CRQ scores in Dyspnea, Fatigue, and Mastery domains.

While a clear relationship between a high presence of meaning and healthy psychological well-being exists, the effect of the search for meaning is less established in the literature. Our results suggest the importance of searching for the meaning in life as it relates to the perception of well-being in critical aspects of quality of life in people living with COPD: breathlessness (most common symptom), fatigue (second most common symptom), and self-management. The value of the search of meaning represents a novel discovery of this report that requires further validation. Dezutter et al distinguishes between adaptive and maladaptive search for MIL, suggesting an adaptive search outlook leads to more acceptance of chronic conditions.3 Our data supports this concept in that those with a high search for meaning perceive less dyspnea and fatigue, while also having higher mastery scores, all critical outcomes in COPD.

Practical Implications

Addressing presence and search for meaning during clinical encounters in clinical practice and self-management programs (pulmonary rehabilitation and health coaching) would offer a complementary and personalized approach to promote better coping, motivation, and wellness.33

Our results provide novel evidence on the importance of meaning in life to sustain and even promote well-being in patients living with COPD. Our findings suggest that fostering high presence of meaning could lead to less fatigue, improved coping ability, and enhanced self-efficacy. While the search for meaning is associated with better dyspnea, fatigue, and sense of mastery.

Use of meaning-centered interventions has demonstrated positive outcomes in chronic diseases,10,19,34-38 but the literature is lacking in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Our models for evaluating the associations of MIL with outcomes are robust (confirmed by bootstrapping) and a good explanation of the variance, as expressed for a high R-squared for a social science investigation. The addition of social support to the model aimed to respond to the concern from previous research regarding the interaction between MIL and social support. Liu et al discovered that those who had strong social support and improved self-management, as demonstrated by a decrease in care support needs, developed a stronger presence of meaning in life and quality of life post hospitalization.15

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, despite multiple sites participating, the population was White, which may not be generalizable to other racial and/or ethnic groups. Second the cross-sectional analysis does not allow us to assess temporal or causal relations between the variables. Studies that investigate these relationships in a longitudinal fashion would allow for a better understanding of these relationships.

Conclusions

Our results innovatively suggest the impact of MIL on critical outcomes in individuals living with COPD. The dissemination of this work is important to increase awareness of the relationship between MIL and improved quality of life for those with COPD. It will stimulate research about MIL with the ultimate aim of promoting conversations about MIL during routine clinical visits, pulmonary rehabilitation and health coaching encounters, and self-management programs.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: CB, MS, and RB contributed to the conception and/or design of the study, data analysis and/or interpretation, writing the article, and revisions prior to submission. JH contributed to the acquisition of data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication. The authors would like to acknowledge the other members of the Mindful Breathing Lab: Maria Benzo, Josh Taylor, and Will Midthun for their contributions.

Data sharing statement: Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article, after deidentification, will be available. Study protocol, statistical analysis plan, and analytic code will not be available. Data will be available beginning 3 months and ending 48 months following article publication. Data will be shared with researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal to achieve the aims of the approved proposal. Proposals should be directed to Benzo.Roberto@mayo.edu. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Declaration of Interests

CB, MS, JH, and RB have no associations or conflicts of interest to disclose.