Running Head: COPD and Comorbid Depression and Anxiety

Funding Support: MNE received grant funding from the American Lung Association for her work on this project.

Date of Acceptance: November 24, 2024 | Publication Online Date: December 4, 2024

Abbreviations: ACE=Anxiety and COPD Evaluation study; ALA-ACRC=American Lung Association Airways Clinical Research Center; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAT=COPD Assessment Test; DSM-V=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; EQ-5D-5L=5-Level EQ-5D; ED=emergency department; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; GAD-7=Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; IQR=interquartile range; LABA=long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA=long-acting muscarinic agonist; MINI=Mini- International Neuropsychiatric Interview; SABA=short-acting beta2- agonist; SAMA=short-acting muscarinic agonist; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PHQ-9=Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PROMIS-29=Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Anxiety and Physical Function; PSQI=Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Citation: Wang JG, Bose S, Holbrook JT, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with COPD and comorbid depression and anxiety: data from a national multicenter cohort study. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(1): 33-42. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2024.0534

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects over 15 million adults in the United States and has a substantial impact on quality of life, representing the second most common cause of disability-adjusted life years lost in the United States.1,2 Psychiatric symptoms are common among individuals with COPD, with 15%−56% and 16%−55% reporting depressive and anxiety symptoms, which carry important implications for COPD outcomes and disease trajectory.3-6 Depressive symptoms have been associated with premature mortality, increased length of hospital stay, and reduced functional capacity, as well as greater breathlessness and lower adherence to COPD treatments.7-9 Anxiety symptoms have been linked with increased health care utilization, heightened respiratory symptoms, diminished quality of life, and greater mortality among people with COPD.10-13

However, the vast majority of these studies utilized screening questionnaires, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)14 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),15 which are commonly used to identify depressive and anxiety symptoms but cannot be used to establish a diagnosis. Although psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses exist on a continuum, there may be differences between people with COPD and heightened psychiatric symptoms and those meeting diagnostic criteria for depression or an anxiety disorder.Despite existing literature on a clear relationship between COPD and both depressive and anxiety symptoms based on screening questionnaires, there is a paucity of data using well-validated diagnostic instruments such as the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). The MINI is a structured interview used as a gold standard for identifying depression and anxiety disorders based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V)16 diagnostic criteria in situations where an interview with a psychiatrist is not feasible.17,18 One national multicenter observational survey study (Anxiety and COPD Evaluation [ACE]) evaluated anxiety screening questionnaire performances among COPD patients using the MINI as the gold standard assessment for the diagnosis of anxiety disorders.19 This study observed that screening questionnaires for anxiety symptoms in COPD patients had only fair to moderate psychometric screening properties. In this study, we performed a secondary analysis of the ACE study, using the MINI to identify individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for depression and anxiety disorders, and report clinical characteristics and disease burden of these comorbidities among individuals with COPD.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This is a cross-sectional, secondary analysis of a multicenter study in stable patients with COPD enrolled at 16 centers within the American Lung Association Airways Clinical Research Center (ALA-ACRC) network in the United States. Other data have been previously reported from this cohort.19,20 Briefly, enrolled participants were ≥40 years of age, had a confirmed diagnosis of COPD (defined by a forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] to forced vital capacity [FVC] ratio of less than 0.7 and a postbronchodilator FEV1 <80% predicted),1 and considered to have clinically stable COPD (absence of exacerbation or worsening symptoms requiring antibiotics or corticosteroids in the 6 weeks prior to enrollment). Those with unstable coronary heart disease, untreated cardiac arrhythmia, unstable angina, major uncontrolled psychiatric disorders that would affect study participation, significant cognitive impairment (defined by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] <18),21 or a condition expected to cause death or an inability to perform study procedures within 6 months were excluded. COPD severity was assessed using Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria for grading airflow obstruction and categorized as GOLD 2 (FEV1 ≥50% and <80% predicted), GOLD 3 (FEV1≥30% and <50% predicted), or GOLD 4 (FEV1<30% predicted).1 Written consent was obtained from all participants and the study was approved by institutional review boards at clinical centers and the data coordinating center.

Procedures and Instruments

Enrolled participants provided demographic and clinical characteristics and underwent a physical examination, spirometry testing, and a 6-minute walk test. Trained research coordinators administered questionnaires on patient-reported symptoms, followed by the structured MINI version 7.0 diagnostic interview. Questionnaires included the modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale (mMRC),22 the COPD Assessment Test (CAT),23,24 the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),25 the 5-Level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire,26,27 the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), questionnaire,28 the HADS,14 the PHQ-9,15 and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Anxiety and Physical Function questionnaire (PROMIS-29).29 Cognitive impairment was assessed using the MoCA test, with a score of 18−25 considered mild cognitive impairment.21 The MINI was used as the gold standard for the identification of major depressive and/or anxiety disorders based on DSM-V diagnostic criteria.16-18Specifically, sections on major depressive and anxiety disorders (panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and agoraphobia) were administered. Questions elicited a “yes/no” response, and a point was given for each “yes” response. Although the primary analysis of this study evaluating questionnaire performance included a lifetime history of panic disorder under anxiety disorders,19 this current analysis classified individuals as having a mood or anxiety disorder based on current symptoms rather than lifetime history. Licensed clinical psychologists reviewed audio-recorded interviews conducted by coordinators for quality assurance and certification.

Statistical Analysis

This is a secondary analysis of data collected from a completed cohort study evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of anxiety questionnaires.19 For this analysis, we summarized socioeconomic and clinical characteristics and patient-reported outcomes, stratified by the presence of current depression and/or an anxiety disorder based on MINI interviews at enrollment. We calculated medians and quartiles for the continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Differences between strata were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis and Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine differences in patient-reported outcomes based on validated questionnaires between those with and without depression or an anxiety disorder. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Because of the small number of cases, multivariate analyses were not performed. All analyses were post hoc (not planned in the study protocol). Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Of 282 individuals screened, 220 eligible participants were enrolled in the study between May 2016 and December 2016. Among the excluded individuals, 45 did not meet spirometric criteria for at least moderate severity COPD, 12 had a MoCA score ≤18, and 5 were not eligible based on both those criteria.

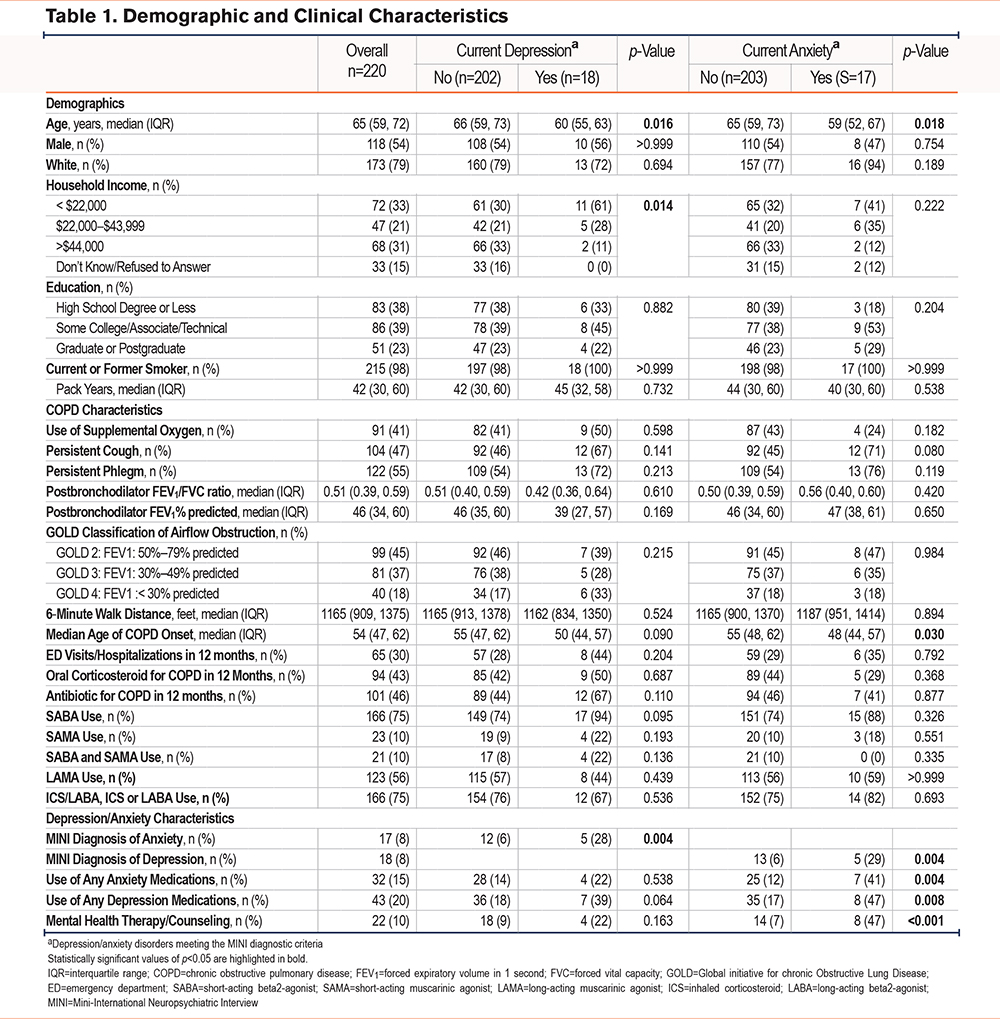

Major Depressive Disorder

Among the total cohort, 18 (8%) participants met MINI diagnostic criteria for a current major depressive disorder. In contrast, 103 (46.8%) participants screened positive for at least mild depressive symptoms with scores ≥5 on the PHQ-9 questionnaire. Participants with a major depressive disorder were younger (median age 60 versus 66 years, p=0.016), and a greater proportion had a household income <$22,000 (61% versus 30%, p=0.014), compared to those without depression (Table 1). There were no significant differences in COPD severity by GOLD classification, spirometric lung function, use of supplemental oxygen, 6-minute walk distance, inhaler use, or recent history of acute COPD exacerbations between those with and without depression.

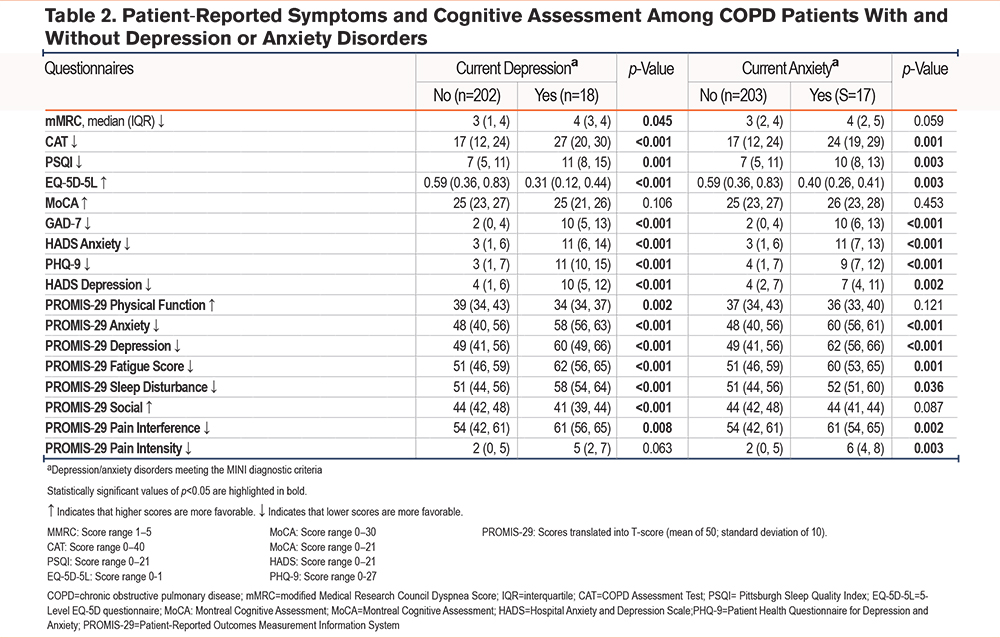

Current depression meeting MINI diagnostic criteria was associated with worse patient-reported outcomes, including greater breathlessness (mMRC 4 versus 3, p=0.045) and COPD-associated symptom burden (CAT 27 versus 17, p<0.001), as well as worse sleep quality (PSQI 11 versus 7, p=0.001), and impaired quality of life (EQ-5D-5L 0.31 versus 0.59, p <0.001; PROMIS-29 physical function 34 versus 39, p=0.002) (Table 2). Participants with depression also reported worse depressive and anxiety symptoms on standard screening questionnaires. Median MoCA scores were 25, which is indicative of mild cognitive impairment, in both those with and without depression (Table 2).

Among participants with a major depressive disorder, only 7 (39%) reported using antidepressant medications and 4 (22%) were receiving mental health counseling. These participants were also more likely to have a concurrent anxiety disorder meeting MINI diagnostic criteria (28% versus 6%, p=0.004) (Table 1).

Anxiety Disorders

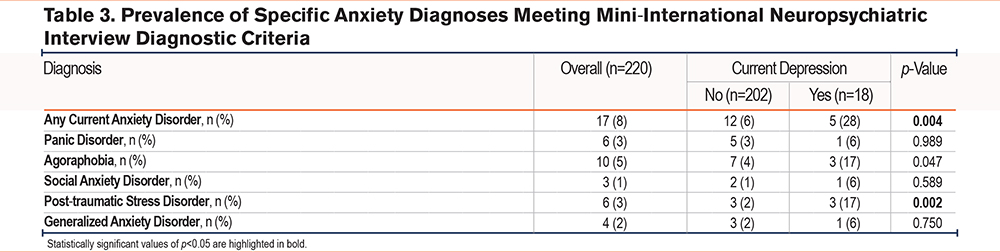

In this cohort, 17 (8%) participants met MINI diagnostic criteria for a current anxiety disorder (Table 1). Agoraphobia was the most common, affecting 10 (59%) participants with current anxiety (Table 3). In contrast, a greater number of people screened positive for at least mild anxiety symptoms, with 38 (17%) reporting a HADS Anxiety score ≥8, and 65 (30%) reporting a GAD-7 score of >4. Patients who met and did not meet MINI diagnostic criteria for a current anxiety disorder had similar demographic characteristics, although those with anxiety were younger at enrollment (59 versus 65 years, p=0.018). Like participants with depression, those with an anxiety disorder experienced more depressive and anxiety symptoms and had generally worse scores on patient-reported measures of disease-specific symptom burden and health-related quality of life, and on most of the PROMIS-29 metrics of well-being (Table 2). However, fewer than half of the participants with a current anxiety disorder used anxiolytics or antidepression medications or received mental health counseling (Table 1).

Based on MINI interviews, only 5 (2%) participants had a concomitant diagnosis of depression and anxiety (Table 1). Three of these 5 were male and reported greater symptom burden, and 3 ranked in the lowest quartile for the 6-minute walk distance and had lower than median lung function. Four had mild cognitive impairment.

Discussion

This is the first multicenter study to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of individuals with COPD and major depressive and/or anxiety disorders meeting MINI diagnostic interview criteria based on the DSM-V. Data were collected in a study conducted at 16 ALA-ACRC centers with the primary aim of determining the sensitivity and specificity of questionnaire measures of anxiety in people with COPD. In this secondary analysis, we found that participants with diagnosed depression or anxiety disorders experienced greater COPD-associated respiratory symptom burden, and reduced functionality and health-related quality of life, compared to those without either psychiatric disorder. Notably, both depression and anxiety were undertreated in this cohort, with substantially fewer than half using an anxiolytic or antidepressant, or undergoing mental health counseling. Despite a growing awareness of psychiatric comorbidities among patients with COPD over the past decade, there remains limited national consensus and clinical guidelines on practical approaches to screening for and managing comorbid mood and anxiety disorders.4 Thus, this study highlights a persistent, major gap in mental health care among patients with COPD.

We also observed that screening questionnaires, including the PHQ-9, HADS Anxiety, and GAD-7, detected more individuals with depressive and anxiety symptoms (47% and 17%−30%, respectively) than those who met MINI diagnostic criteria for having a major depressive or anxiety disorder (8% each). Unlike screening instruments – which are inherently designed to have higher sensitivity and lower specificity to reduce the probability of missing a diagnosis – the well-validated MINI is designed to identify major depressive and anxiety disorders based on DSM-V diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, commonly used screening questionnaires cannot accurately distinguish psychiatric from somatic symptoms that may coexist among COPD patients and lack detailed measures of functional impairment required to meet diagnostic criteria.3,19 As a result, findings from this study using the MINI diagnostic assessment extends existing knowledge on relationships between depressive and anxiety symptoms and patient-reported outcomes to also include those meeting MINI diagnostic criteria for depression and anxiety disorders.

Participants with a major depressive disorder meeting MINI diagnostic criteria were significantly younger, and a greater percentage reported lower household income compared to those without depression. Individuals with anxiety disorders meeting MINI diagnostic criteria were also significantly younger than those without anxiety. The few participants with concurrent depression and anxiety had more severe COPD and greater symptom burden. Otherwise, there were no significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics among those with and without depression or anxiety disorders.

However, compared to those without either psychiatric disorder, patients with depression or anxiety disorders experienced more functional impairment and disability due to COPD-associated respiratory symptoms, poorer quality of sleep, and reduced health-related quality of life, including increased fatigue and pain limiting daily activities. This is consistent with and extends prior work using screening questionnaires that linked elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms with reduced COPD-associated quality of life.6,30 These findings are important, as uncontrolled psychiatric comorbidities may contribute to maladaptive behaviors that influence COPD disease trajectory and perpetuate a cycle of disabling symptoms.3,31 For example, poorly controlled depression and anxiety disorders may reduce disease-related coping, impair self-care behaviors such as participation in pulmonary rehabilitation and adherence to smoking cessation, and promote poor medication adherence, all of which increase the risk for COPD exacerbations and hospitalizations.6,10,32-36 In this regard, we have found that the most common anxiety comorbidity in this cohort is agoraphobia, a condition that can limit activity, health care use, and social involvement.37 Anxious feelings of fear and worry may also amplify symptoms typically attributed to COPD, including heightened sensations of breathlessness and poor exercise tolerance. These experiences then lead to further social isolation, sensations of panic, and feelings of helplessness, perpetuating a cycle of reciprocal symptoms.34,38-40 This bidirectional, intertwined relationship between psychiatric disorders and COPD further highlights the gravity of mental health as an integral but underappreciated component of COPD care.41,42

Despite this, there remains a lack of widespread clinical awareness of these psychiatric disorders resulting in under-recognition and undertreatment.3,42 One prior cross-sectional study from nearly 2 decades ago identified that fewer than a third of COPD patients with depression or anxiety were receiving psychiatric treatment.43 Our study affirms a persistent care gap, with only a minority of participants with depression or anxiety in this cohort reporting using anxiolytics and/or antidepressants, or receiving mental health counseling. Furthermore, those with diagnosed depression or anxiety scored poorly on metrics evaluating health-related quality of life and reported a high burden of depressive or anxiety symptoms, suggesting inadequate treatment. These results emphasize a necessity for not only timely recognition and diagnosis but also an integrated multidisciplinary support network for the effective treatment of these common mental health comorbidities in patients with COPD.

This study has notable strengths. Our cohort included participants from multiple centers across the United States, enhancing generalizability. We utilized both the structured MINI with trained administrators to accurately identify those meeting diagnostic criteria for depression or anxiety disorders and administered several screening questionnaires to concurrently gauge depressive and anxiety symptom burden and functional impact. While the MINI has been used in COPD patients in smaller single-center studies,44,45 ours is the first and largest multicenter study to describe characteristics between individuals who meet MINI diagnostic criteria for depression and anxiety disorders and those who do not. However, we also acknowledge several limitations. The main aim of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics of COPD patients with depression and anxiety disorders and to capture the burden of these psychiatric disorders in this population. However, the relatively low number of participants with depression or anxiety disorders based on MINI diagnostic criteria potentially reduced the power to account for confounders and evaluate associations and interdependencies between COPD characteristics and depression or anxiety disorders. Furthermore, as this was a cross-sectional analysis, it remains unclear how symptoms may change over time throughout the disease course, and if alleviating the burden of psychiatric disorders would improve COPD outcomes. However, our study serves to inform larger, longitudinal studies dedicated to understanding how mental health comorbidities may influence both patient-reported outcomes and COPD disease trajectory.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional analysis of a national, multicenter cohort of patients with COPD found that major depressive and anxiety disorders meeting MINI diagnostic interview criteria based on the DSM-V were relatively common comorbidities that remain underrecognized and undertreated, despite a profound impact on symptom burden affecting daily function and quality of life. There is a need to understand patient and systems-level barriers to the accurate diagnosis of mood and anxiety disorders in this population, and for effective strategies to manage these conditions as an integral part of comprehensive COPD care.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: JGW, SB, LN, and JTH contributed to data analyses and interpretation, and manuscript writing. NAH, AMY, MNE, and RAW contributed to the conception of the study, and data collection, analyses, and interpretation. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

American Lung Association Airways Clinical Research Centers

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, Texas

Nicola Hanania, MD, MS, FCCP (principal investigator), Marianna Sockrider, MD, PhD (co-principal investigator), Laura Bertrand, RN, RPFT (principal clinic coordinator), Mustafa Atik, MD (coordinator), Amit Parulekar, MD, Harold Farber, MD (study physicians). Former member: Blanca A. Lopez, LVN.

Columbia University–New York University Consortium

New York, New York

Joan Reibman, MD, (principal investigator), Emily DiMango, MD, Linda Rogers, MD, (co-principal investigators), Karen Carapetyan, MA (principal clinic coordinator at New York University), Kristina Rivera, MPH, Melissa Scheuerman, BSc (clinic coordinators at Columbia University). Former members: Elizabeth Fiorino, MD, Newel Bryce-Robinson.

Duke University Medical Center

Durham, North Carolina

Loretta G. Que, MD (principal investigator), Jason Lang, MD, PhD (coprincipal investigator), Erika M. Coleman, BS, Eli Morgan, BA (coordinators), Heather Kuehn, BS (regulatory coordinator), Anne Matthews, MD, Devon Paul, MD, MPH (study physicians), Catherine Foss, BS, RRT, CCRC (principal clinic coordinator), Nicholas Eberlein, BA.

Illinois Consortium

Chicago, Illinois

Lewis Smith, MD (principal investigator), Ravi Kalhan, MD, James Moy, MD, Edward Naureckas, MD (co-principal investigators), Jenny Hixon, BS, CCRC (principal clinic coordinator), Zenobia Gonsalves, Virginia Zagaja, Jennifer Kustwin, Ben Xu, BS, CCRC, Thomas Matthews, MPH, RRT, Lucius Robinson III, Noopur Singh (coordinators).

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-New Orleans, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care/Allergy and Immunology

New Orleans, Louisiana

Kyle Happel, MD (principal investigator), Marie C. Sandi, FNP-BC (principal clinic coordinator), Jennifer M. Graham, Katelyn Sullivan, Elizabeth Poretta (data system operators).

National Jewish Health

Denver, Colorado

Rohit Katial, MD (principal investigator), Flavia Hoyte, MD, Maria Rojas (principal clinic coordinator).

St. Louis Asthma Clinical Research Center: Washington University

St. Louis, Missouri

Mario Castro, MD, MPH (principal investigator), Leonard B. Bacharier, MD, Kaharu Sumino, MD, Roger D. Yusen, MD, MPH (co-investigators), Jaime J. Tarsi, RN, MPH (principal clinic coordinator), Brenda Patterson, MSN, RN, FNP (coordinator), Terri Montgomery (data entry operator).

St. Vincent Hospital and Health Care Center, Inc.

Indianapolis, Indiana

Michael Busk, MD, MPH (principal investigator), Debra Weiss (principal clinic coordinator). Former member: Kimberly Sundblad.

Vermont Lung Center at the University of Vermont

Colchester, Vermont

Charles Irvin, PhD (principal investigator), Anne E. Dixon, MD, David A. Kaminsky, MD, Charlotte Teneback, MD, Jothi Kanagalingam, MD (co-principal investigators), Stephanie M. Burns (principal clinic coordinator), Kathleen Dwinell (data system operator).

University of Arizona

Tucson, Arizona

Lynn B. Gerald, PhD, MSPH (principal investigator), James L. Goodwin, PhD, Mark A. Brown, MD (co-investigators), Tara F. Carr, MD, Cristine E. Berry, MD, MHS, Christian Bime, MD, Mark A. Goforth, FNP-C. (study physicians), Elizabeth A. Ryan, BS, RRT (principal clinic coordinator), Jesus A. Wences, BS, Silvia L. Lopez, RN, Janette C. Priefert, BS (coordinators), Natalie S. Provencio-Dean, BS, Destinee R. Ogas (data system operator). Former member: Valerie R. Bloss, BS.

University of California

San Diego, California

Stephen I. Wasserman, MD (principal investigator), Joe W. Ramsdell, MD, Xavier T. Soler, MD, PhD (co-principal investigators), Katie H. Kinninger, RCP (principal clinic coordinator), Amber J. Martineau (coordinator). Former members: Tonya Greene, Samang Ung.

University of Miami– University of South Florida

Miami, Florida and Tampa, Florida

Adam Wanner, MD (principal investigator, Miami), Richard Lockey, MD (principal investigator, Tampa), Thomas B. Casale, MD (co-principal investigator, Tampa), Andreas Schmid, MD, Michael Campos, MD (co-principal investigators, Miami), Monroe King, DO (co-principal investigator, Tampa), Eliana S. Mendes, MD (principal clinic coordinator, Miami), Catherine Renee Smith (principal clinic coordinator, Tampa), Jeaneen Ahmad, Patricia D. Rebolledo, Johana Arana, Lilian Cadet, Shawna Atha, CRC, Rebecca McCrery, Sarah M. Croker, BA (coordinators).

University of Missouri, Kansas City School of Medicine

Kansas City, Missouri

Gary Salzman, MD (principal investigator), Asem Abdeljalil, MD, Abid Bhat, MD, Ashraf Gohar, MD (co-principal investigators), Mary Reed, RN, BSN, CCRC (principal clinic coordinator).

University of Virginia

Charlottesville, Virginia

W. Gerald Teague, MD (principal investigator), Larry Borish, MD (co-principal investigator), Kristin W. Wavell, BS, CCRC (principal clinic coordinator), Theresa A. Altherr (study coordinator). Former members: Donna Wolf, PhD, Shahleen Ahmed.

Chairman’s Office, University of Alabama

Birmingham, Alabama

William C. Bailey, MD.

Data Coordinating Center, Johns Hopkins University Center for Clinical Trials

Baltimore, Maryland

Robert Wise, MD (center director), Janet Holbrook, PhD, MPH (deputy director), Alexis Rea (principal coordinator), Joy Saams, RN, Anne Casper, Robert Henderson, Andrea Lears, BS, Deborah Nowakowski, David Shade, JD, Elizabeth Sugar, PhD. Former members: Bethany Grove, Adante Hart, BS, Lea T. Drye, PhD.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board

Vernon M. Chinchilli, MD (chair), Paul N. Lanken, MD, Donald P. Tashkin, MD.

Project Office, American Lung Association

New York, New York

Alexandra Sierra (project officer), Norman H. Edelman, MD. (scientific consultant), Susan Rappaport, MPH. The sponsor had a role in the management and review of the study. Former member: Elizabeth Lancet, MPH.

Declaration of Interests

SB has received funding for research support from 4DMedical. MNE has received grant funding from the American Lung Association for her work on this project. NAH received honoraria for serving as an advisor/consultant for GSK, Sanofi, Genentech, Verona Pharma, Astra Zeneca, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and research support from GSK, Sanofi, Astra Zeneca, and Genentech. JGW, JTH, LN, AMY, and RAW have nothing to declare.