Running Head: Patient-Inspired Health Concepts for COPD Trials

Funding Support: This study is part of the COPD Foundation’s Patient-Inspired Validation of Outcome Tools (PIVOT) project, supported by unrestricted research grants from the following companies: Apogee Therapeutics Inc. (2024–2025), Chiesi (2023–2025), CSL Behring (2023–2024), GSK (2023–2025), Sanofi (2024–2025), Viatris (2023–2025), and Zambon (2023). Thermo Fisher Scientific provided in-kind contribution to PIVOT as part of a strategic collaboration with the COPD Foundation.

Date of Acceptance: July 3, 2025 | Published Online: July 18, 2025

Abbreviations: AECOPD=acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CASP=Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; COA=clinical outcome assessment; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DET=data extraction table; E-RS=Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; GOLD=Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HRQoL=health-related quality of life; PIVOT=Patient-Inspired Validation of Outcome Tools; PR=pulmonary rehabilitation; PRO=patient-reported outcome; RoB=risk of bias; SD=standard deviation

Citation: Duenas A, Kornalska K, Hamilton A. A metasynthesis of qualitative literature to inform the selection of meaningful and measurable health concepts for clinical trials in COPD. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(5): 426-439. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0633

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (343KB)

Introduction

The advancement of new medical treatments depends on clinical trial results and regulatory approval, which require that a drug must demonstrate clinical benefit—a favorable effect on a meaningful aspect of how a patient feels or functions in their life, or a favorable effect on survival.1 In recent years, guidance provided by the Food and Drug Administration on patient-focused drug development has offered an opportunity to better incorporate the patient perspective into trial design, ensuring, for example, that the needs of the patient population being studied are taken into account when determining what to measure in the trial.2-4 This is particularly important at the beginning of the measurement strategy process, where meaningful and measurable health concepts are identified. These concepts include aspects of an individual’s clinical, biological, physical, or functional state, or health experiences resulting from their disease/condition.2,5,6 Identifying key health concepts allows for the subsequent selection of “fit-for-purpose” outcome measures for the evaluation of treatment benefit in clinical trials.6

In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) clinical trials, efficacy evaluation historically relied on forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) as a measure of lung function.7,8 However, a growing body of evidence suggests the need to look beyond FEV1 for the evaluation of clinical benefit in COPD and to consider more patient-focused measures.7 The development and validation of patient-focused measures can be strengthened by clearly differentiating between the meaningful and measurable health concept (“what to measure”) and the measurement instrument (“how to measure”). Understanding the perceptions of people living with COPD plays a key role in identifying meaningful and measurable health concepts that can be incorporated into clinical trials.

A substantial amount of qualitative research in COPD describes the patient experience, providing valuable insights to help identify patient-inspired health concepts that can be utilized for clinical outcome assessment (COA) development, validation, and selection.9,10 Previous qualitative literature reviews in COPD have generally focused on specific targeted aspects of the patient experience, such as advanced COPD, particular COPD symptoms or impacts, or other aspects of disease management, making it difficult to identify shared or different experiences across COPD populations.11-14 A literature review that synthesizes findings across qualitative studies of the patient experience is a valuable first step in identifying the meaningful aspects of a person's life that are affected by COPD and the terms and phrases patients use to describe them.

As part of the COPD Foundation’s Patient-Inspired Validation of Outcome Tools (PIVOT) program,5,15 this metasynthesis summarizes qualitative research exploring patient experiences with the symptoms and life impacts of COPD to inform the development of a unified set of patient-inspired health concepts to consider when developing, validating, and/or selecting outcome measures for COPD clinical trials.

Methods

Rationale and Objective

This review summarizes and synthesizes qualitative research that explores how individuals diagnosed with COPD describe their disease to inform the research question “What aspects of COPD influence a patient’s lived experience with the disease?” A key focus of the review was to compare how researchers and patients name and describe these experiences. Results from this review will support the identification of relevant patient-inspired health concepts that can be considered in the context of COA development and validation for COPD clinical trials.

Preplanned Search Strategy

This review was limited to empirical qualitative studies in the MEDLINE/PubMed and Embase databases that were published in the last 10 years. Search terms for medical subject headings and free-text keywords were based on the terms and adjectives for COPD, signs and symptoms, and “quality of life.” The search strategy and limits are available in Supplement 1 in the online supplement. This study is reported according to the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research statement checklist.16

Inclusion Criteria and Study Selection

The inclusion criteria were based on the population, phenomenon of interest, context, and study design.17 The phenomenon of interest included patient-reported concepts (COPD symptoms and impacts, quality of life) as it pertained to disease experience. Qualitative research that included concept elicitation interviews, cognitive debriefing, focus groups, or mixed methods incorporating patient interviews was considered. Quantitative observational studies, randomized clinical trials, economic studies, and case studies were excluded. No restrictions were placed on the setting/country of the study. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by 2 researchers (CJM, AJ) using Nested Knowledge®.18 Relevant articles were further screened for full-text review, followed by critical appraisal (Supplement 2 in the online supplement).

Critical Appraisal of Studies

Articles meeting inclusion criteria were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative studies,19 ensuring a standardized and structured approach when assessing the quality of research in the following domains: research design, sampling strategy, data collection, reflexivity (including the relationship between the researcher and the patients), ethical considerations, rigor of the data analysis, clear statement of the findings, and value of the research. The CASP checklist was used because it systematically addresses the basic principles of good scientific design, assessing the trustworthiness, relevance, and reliability of the published results.20-22

Two researchers (KK, CJM) conducted the critical appraisal, and a third senior researcher (AD) reviewed the studies to resolve any discrepancies. Articles with a low risk of bias were selected for data extraction (Supplement 2 in the online supplement). Studies were deemed to have a low risk of bias when high-strength evidence was present in at least 7 out of the 10 CASP questions; studies that did not meet criteria for question 5 (data collection addressed research question), question 8 (data analysis was rigorous), and question 9 (clear statement of findings) were excluded.

Data Extraction Procedures

Data extracted from eligible studies were entered into a Microsoft Excel® data extraction table (DET), organized by first author, publication year, study design, patient population, methods, and research results, including pre-identified labels based on the Patient-Focused Medicines Development Patient Experience Data patient navigator tool, which outlines key areas that are important for patients in research (i.e., signs/symptoms, functioning).23 The DET was piloted by extracting a sample of eligible studies and expanded to include labels relevant to COPD, such as disease-specific symptoms and impacts, as well as broader patient experiences related to social determinants, such as financial constraints, environmental factors, and other health factors. Three qualitative researchers (CJM, KK, AJ) extracted data from all eligible studies, and a senior researcher (AD) reviewed the DET for completeness before the metasynthesis.

Metasynthesis

This qualitative metasynthesis was based on the methodology by Sandelowski and Barroso.24 This approach is iterative and systematic, focusing on summarizing methods and results from qualitative literature, then synthesizing themes and selected quotes from patients who participated in each study to identify new insights from the patient perspective across all studies.24 This method allows researchers to preserve themes from original published qualitative research while allowing new themes to emerge across multiple studies. Although other considerations and complexities of qualitative metasynthesis were considered,25-27 an applied approach was necessary to develop a nomenclature of health concepts. This was done by preparing and grouping the extracted data in Microsoft Excel, then summarizing the frequencies of high-level themes across studies. To develop a taxonomy of themes that could be applied to the context of clinical trials, patient-level data (quotes available in each study) were further assessed and organized into 3 levels according to the author’s interpretation of quotes, direct patient quotes from the study, and the reviewers’ assessment/interpretation of the data.

Two researchers (AD, KK) conducted a constant comparative analysis to independently identify themes across the eligible studies using results (themes and patient quotes) from the DET. The same researchers discussed these results to improve the reflexivity of their interpretation of the data from each study and find any new themes or considerations. One researcher (KK) summarized and aggregated the DET results, which included representative quotes from patients. This summary was then reviewed and revised by another researcher (AD). Subsequent discussions with senior reviewers (AH, NLK) led to the identification of the final themes. Additional information on the metasynthesis, including a description of the steps involved in this process, is provided in Supplement 3 in the online supplement.

Results

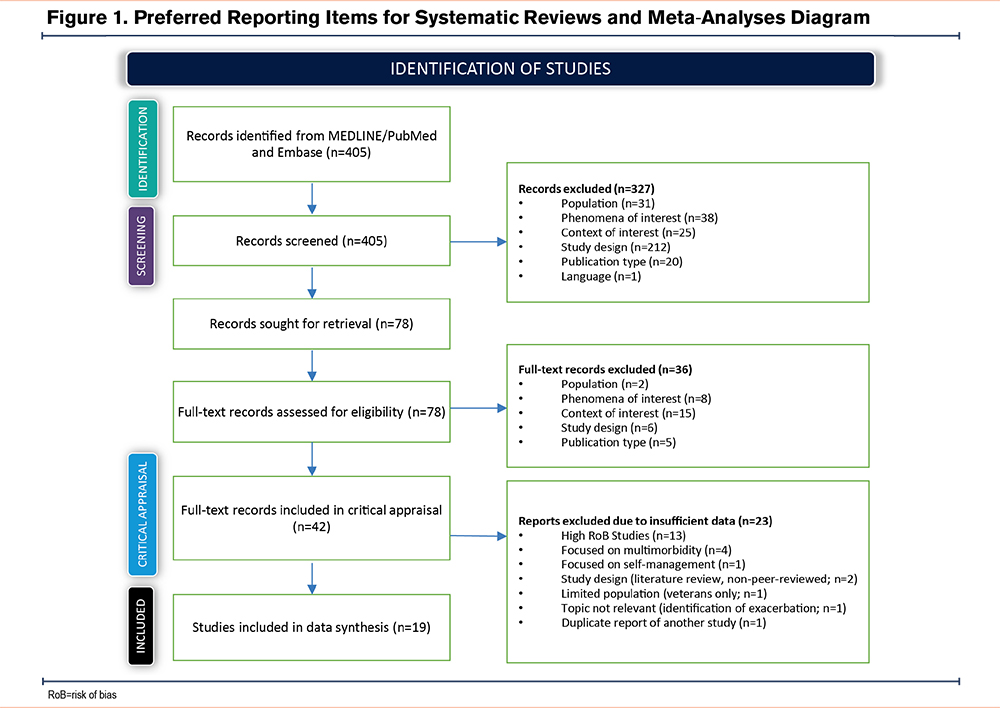

Out of 405 qualitative research abstracts identified and reviewed from database searches, 78 articles were assessed for full-text review, resulting in 42 articles meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Twenty-three of the 42 articles were excluded after CASP assessment because of limited information on methods/analysis. Consequently, 19 qualitative studies were selected for data extraction and metasynthesis. Details about the selection of studies and assessment via the CASP checklist are available in Supplement 2 in the online supplement.

Summary of Eligible Studies

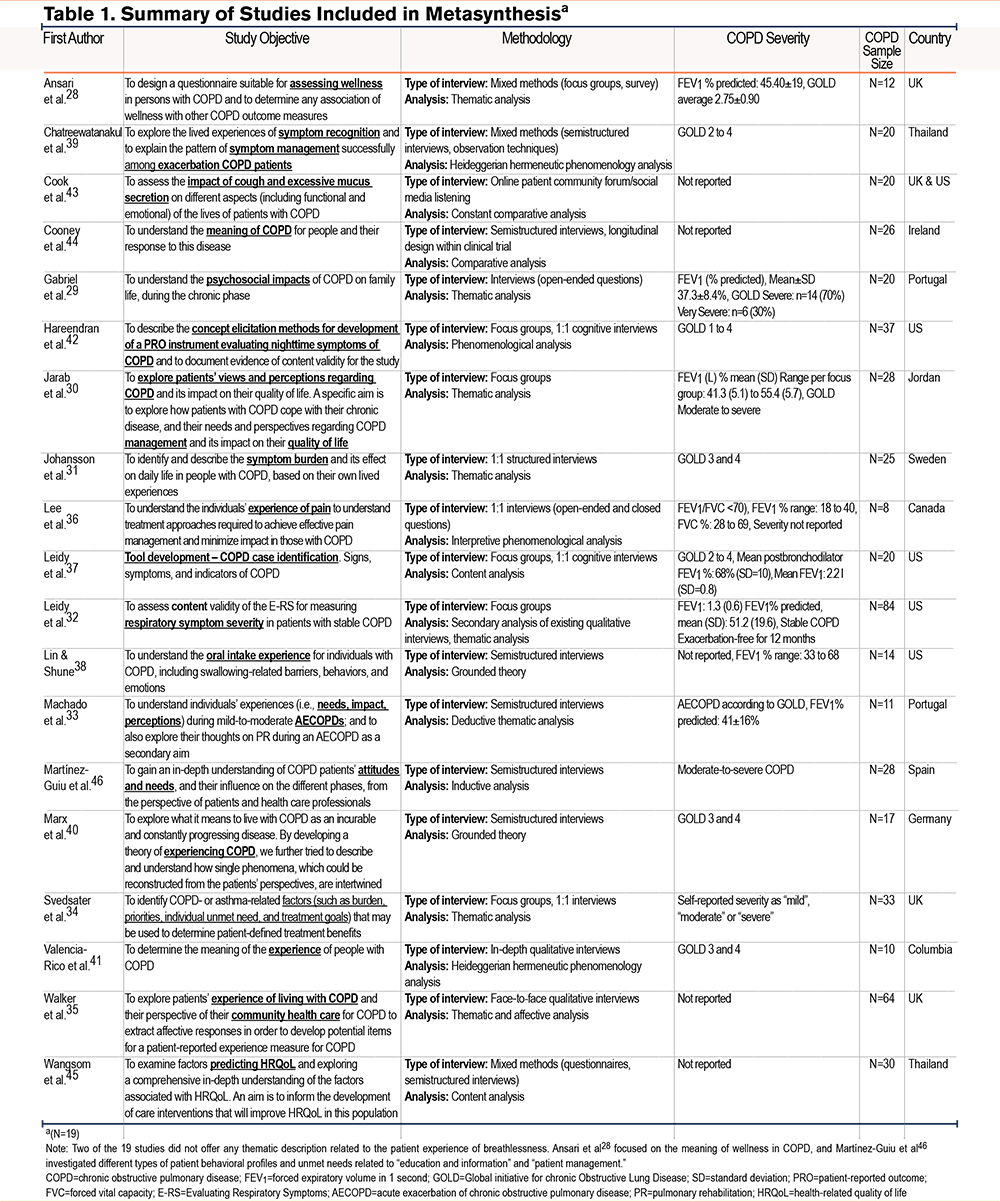

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of eligible studies28-46 and presents qualitative research from 11 countries: the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Ireland, Jordan, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Thailand. Each study explored an aspect of the patient experience of living with COPD. Study objectives included understanding the symptom burden of COPD, exploring perceptions about the meaning of COPD, identifying unmet needs, and assessing the impacts on specific symptoms (e.g., cough, mucus). Study design methods included individual or semi-structured interviews (12, 63.2%), focus groups (5, 26%), a combination of both focus group/ semi-structured interviews (1, 5.2%), and social media listening (1, 5.2%). Of these, 2 studies included qualitative methods as part of a mixed methods survey and 2 were part of instrument development studies which combined focus groups and cognitive interviews. Thematic analysis was the most common method for qualitative analysis (8, 42.1%).28-35

There were a total of 507 participants with COPD across all 19 studies, with samples ranging from 8 participants to a maximum of 64 participants. Just over half of the participants across studies were men (259; 51.1%), and all participants were between 38 and 88 years old. Only 36.8% of the studies reported on ethnicity/race, employment status, or comorbidities (Supplement 4 in the online supplement).

The severity of lung function impairment was not always described, and only 8 studies (42.1%) provided data on FEV1.28-30,32,33,36-38 Nine studies included patients with moderate-to-severe impairment (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] criteria 2 to 4; 47.3%),28,29,31,33,36,37,39-41 with one reference42 to GOLD 1. COPD severity was described as moderate to severe (5.2%)29 and very severe (5.2%),34 or was self-reported as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe” (5.2%).34 Seven studies (36.8%)32,35,36,38,43-45 did not report patients’ disease severity level.

Qualitative Metasynthesis

COPD themes were first summarized and organized in the DET by signs, symptoms, functioning, global quality of life, perceived health status, and external factors that may impact COPD or disease severity. The exploration of symptoms focused on the themes and descriptive terms presented by study authors, which were compared with the terminology used directly by study participants (from the patient quotes provided in each article). A review of patient quotes found emergent latent themes related to the co-occurrence of symptoms and additional impacts on daily life not specifically reported by the study authors. Overall, while there was variation in the terms used by patients and authors to describe the experience of COPD, it was clear that there was conceptual consistency between the descriptions of patient experiences related to selected symptoms and impacts. These insights from the metasynthesis yielded 4 main organizational categories: (1) COPD symptoms, (2) physical activity, (3) social and role functioning, and (4) emotional and psychological impacts.

COPD Symptoms

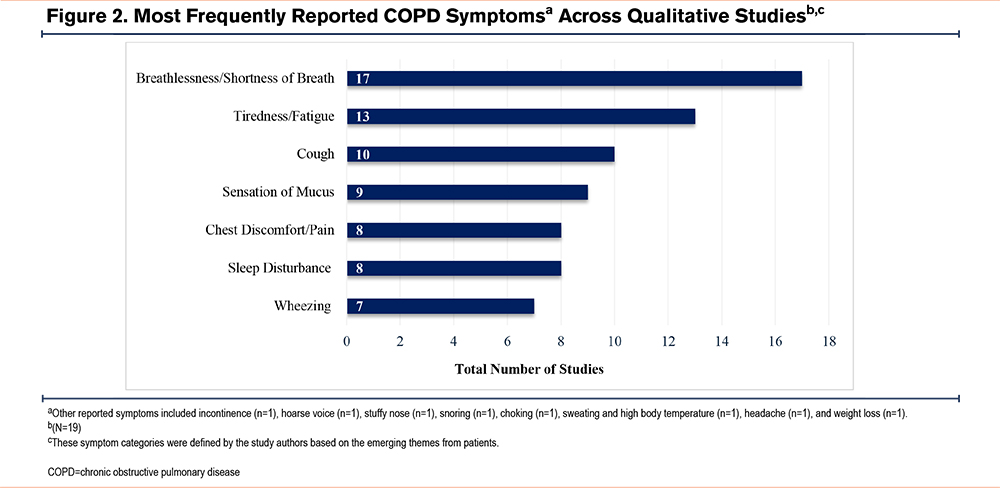

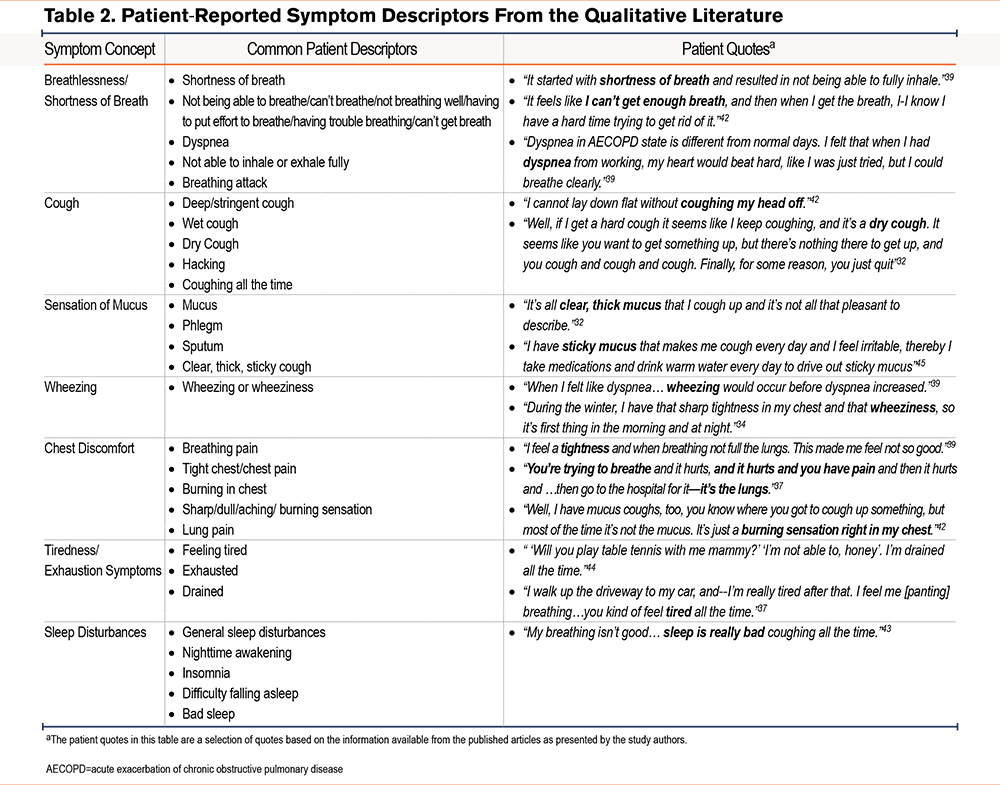

The symptoms most frequently mentioned by authors across studies are shown in Figure 2. These were compared with the patient terminology and descriptions of symptoms from the available quotes within each study publication (Table 2). Additional patient quotes are presented in Supplement 5 in the online supplement.

Respiratory Symptoms

Breathlessness and/or shortness of breath were hallmark symptoms used in nearly all studies (17, 89.4%).29-45 Cough was another frequently reported symptom across studies (10, 52.6%), followed by mucus (9, 47.3%). Although there are some similarities between terms used by authors and patients to describe the COPD experience, patients provided more descriptive and narrative explanations when discussing their symptoms and noted the intensity of the symptoms, how often they occur, and overall symptom burden. One example is the term “breathlessness,” which encompasses various patient phrases describing difficulty breathing or inhaling. Patients also described their cough experience in a variety of ways, using terms such as “dry cough,” “mucus cough,” “hard cough,” and “deep and stringent cough.”

Other COPD symptoms, such as wheezing (7, 36.8%)33,34,37-39,42,43 and chest discomfort (6, 31.5%),33,34,36,37,39,42are part of the lived experience for some patients. Limited detail was provided within the studies themselves about wheezing or “wheeziness,” a term patients used without providing further description or context (4, 57.1%).27,31,32,37 Chest discomfort was reported as “chest tightness” or “pain/burning” in the chest area or lung (6, 75%).22,26,27,30,32,34-37,39 Pain attributed to cough, mucus, or breathing was reported by patients in 4 of these studies.34,36,37,39 One study by Lee et al36 specifically explored the experience of pain in participants with COPD who may have other comorbid pain-related conditions.

Nonrespiratory Symptoms

The authors identified fatigue, tiredness, and exhaustion as prominent features of COPD; more than half of the studies (13, 68.4%) highlighted terminology such as “fatigue” and “tired/exhaustion,”29,33,34,36-38,43 “low energy/lack of energy,”28,33,37 and “slowing down of life.”30 Patients did not explicitly use the term “fatigue” to describe their experience. Patient narratives on their general day-to-day tiredness and exhaustion highlight the range of severity (intensity) of this symptom.

Sleep experiences or “sleep disturbances” were also highlighted in 8 studies (8, 42.1%).28,29,33,34,37,39,42,43 Nighttime awakening was one theme identified in a study by Hareendran et al, which specifically evaluated nighttime symptoms of COPD.42 Sleep disturbances were often attributed to cough, wheezing, and shortness of breath.33,43

Concurrent/Interactive Nature of Symptoms

Study participants often described the interaction between breathlessness, cough, and mucus, which led to other downstream symptoms and impacts. For example, cough was a frequent trigger of shortness of breath as reported by Lin and Shune.38

- “Well, [breathing gets] definitely worse because I’m coughing, which is an antibreathing process, and so I’m not getting- I’m not having control of my breathing.”38

Svedsater et al also reported that mucus buildup was shown to affect breathing and that coughing was used as a method to dispel mucus.34 As the frequency of cough intensifies, this triggers further downstream fatigue/tiredness/exhaustion symptoms. The cycle of needing to expel mucus, coughing, and being breathless/short of breath was discussed, along with feeling exhausted from not getting enough rest, “That’s very exhausting, to cough hard with COPD. It really wears you out fast.”38 Overall, the narratives from patients show a pattern of distinct COPD symptoms, which may not always occur in isolation.

The intensity of symptoms was also explicitly addressed with acute exacerbations of COPD in 4 studies.29,33,39,40 Individuals with a history of exacerbation were more likely to recognize variations in their signs and symptoms, indicating the possible onset of an acute worsening. The articles described these variations as a pattern starting with any of the following: dyspnea, cough, tightness in the chest, throat obstruction, wheezing, hoarse voice, or stuffy nose.39

Physical Activity

Limitations in physical activity varied from light (sitting or bending down) to moderate (walking short distances and needing to rest when walking) to more strenuous activity (climbing stairs).32,33 Patients expressed various difficulties with physical activity, such as weak hand and leg muscles, mobility constraints, performing activities more slowly, needing to rest, and a decreased ability to do any type of physical activity in general. Limitations were often expressed about regular activities of daily living, such as getting dressed, showering, making the bed, getting the kids off to school, gardening, taking a walk, and playing with grandchildren.

Relationship Between Symptoms and Physical Activity

Breathlessness and physical activity were often discussed together when patients described their breathing issues. Various types of ambulatory activity led to breathlessness:

- “…if the grandchildren … went suddenly out the back and I had to make chase after them. You’d get kind of winded, you know …”44

- "[. . .] if I take a walk, for example, to go out [sic] from here where you are now, suddenly I have to rest over there."41

- "… I go too fast some place and I get a little bit breathless … [I get breathless] if I went up the stairs too quick.”44

- “When I try to walk out there, I can go maybe 50 yards and I have to stop and lean up against a post or something to catch my breath.”32

Breathlessness often limited the participants’ ability to perform various regular activities of daily living, including personal care activities, household chores, and hobbies:

- “Taking a shower makes me short…I get short of breath.”32

- “My chest feels very tight. It seems that I have to make a huge effort to be able to breathe.”33

- “And I’ve got to get the kids off to school, that’s when the short of breath gets worse in the morning, and the school run.”34

Patients reported the need to move slowly to control their breath, as well as the avoidance of moving around the house too quickly or walking uphill.31,44 These types of breathing issues interfered with patients’ overall well-being; more severe episodes of breathlessness had a greater impact on patients’ lives.

Tiredness and exhaustion also impaired patients’ ability to do their daily activities.

- “Sometimes it is very tiring. I came back from holiday last Tuesday night, and on Friday, I was cleaning out a bedroom and I was very tired out. Something that years ago would have [been] 20 min—takes a long time."35

- "I find changing the bed [the linen] I’m wrecked.”44

- "This affects me on a daily basis as I am continually tired, the simplest of tasks take ages to complete, and leave me exhausted and breathless, and depressed as I fear losing my independence."43

- “I feel really tired in the morning, I barely get up. As soon as I put my feet on the ground, I start dressing, and I’m already tired.”33

In one study on the oral intake experience in patients with COPD, patients described how coughing interfered with eating and drinking, causing difficulty in swallowing and a sensation of choking.38

Social and Role Functioning

Patients described various limitations in their family roles, relationships, and employment as a result of COPD. These impacts on social activities led to embarrassment, avoidance, or withdrawal from social activities, and, in the worst cases, self-isolation. In some instances, the initial limitations with role functioning were specifically linked to breathlessness.

- "I am frustrated because things that I did 2 years ago I cannot do now. My wife won’t take me out as it is embarrassing to me because I cannot get my breath."30

Patients described feeling like they could not go out or leave the house because they could not “get [their] breath.” Spending time with children and romantic relationships were also significantly affected.29,30,34,36,41,43-45

Persistent cough, or “coughing all the time,” impacted social activities. Patients avoided interactions or hid to mitigate the embarrassment of coughing in public or around others.

- “Nobody wants to be near me in the mornings believe me … I get into the bathroom I know it’s horrendously bad. I like to go away on my own because I know that I’d embarrass everybody …”44

Another example highlights how a heightened awareness about COPD limits hobbies with a social dimension.

- “COPD prevents me from doing a lot of what I once enjoyed, including singing, it can be embarrassing at times when you have to explain why you can’t do certain things.”44

This concern about being singled out for coughing or breathing heavily in public indicates the stigmatization of COPD.35 This issue is also experienced in the workplace where the need to cough to dispel mucus impacts employment, necessitating more frequent breaks during the day and, in some cases, reduced work hours.

Emotional and Psychological Impacts

A myriad of emotional and psychological impacts experienced by patients were described across studies: frustration, irritability, anger, desperation, anxiety, panic, fear, despondence, sadness, helplessness, dependency on others, limitations in freedom and independence, feeling self-conscious, embarrassment, sense of isolation, loneliness, feelings of guilt, and not being understood. Although the emotional and psychological experience has many dimensions, an overall theme of the symptom experience is the inability to perform personally meaningful activities. Patient narratives often described how this led to embarrassment, frustration, and fear/anxiety.

- “Not being able to breathe, and unable to do physical activity. The worst part, your mind tells you that you can do it, because you’ve been doing it your whole life. Your body shuts the thinking down real quick. Leaving me very frustrated.”43

This frustration is a common theme of COPD, given the challenges with symptom experience and management. Other themes included anxiety or panic from a fear of losing independence due to episodes of breathlessness. Patients commented on anxiety being a trigger, leading to difficulty breathing, then wheezing and coughing:

- “[When I panic] it’s harder and harder [to breathe]. I start into the wheezing phase, then coughing.”38

Emotionally, patients expressed daily irritability and embarrassment due to COPD symptoms, specifically with visible symptoms such as coughing up mucus in public. The feeling of embarrassment persisted even in the presence of family.

- “I have sticky mucous that makes me cough every day and I feel irritable, thereby, I take medications and drink warm water every day to drive out sticky mucous.”45

- “The sputum makes me feel desperate, and then I bother my family, I know it.”33

Participants reported that their cough led to frustration and other negative emotions due to the impact on basic functions like eating.

- “During your mealtime, you can potentially develop coughing or shortness of breath, and these actions can lead to some negative emotions.”38

Walker et al35observed that COPD exacerbation was associated with strong negative emotions such as fear and anxiety, “Like having a plastic bag over your head…so frightening.” This level of anxiety was elevated during exacerbations, with descriptions such as a threat to life, a feeling of terror, and a fear of dying or suffocation.

Additional Insights

Environmental factors such as exposure to smells (detergents, perfumes), pollutants/chemicals, and fumes play a role in triggering COPD symptoms like breathlessness35 and chest tightness.37

- “Fumes from cars give it to me, and that cough persisted for a while. I was on a bus, and if the doors are open, the fumes… make me cough. Usually, I get a tickle.”35

Environmental triggers of exacerbations were also discussed and linked to exposure due to occupations.

- “Sometimes after finishing repairs on a house, I would feel moody, so I took bronchodilators…and yes, I was a home improvement technician. It was not good for my illness, because it stimulated [acute exacerbation of] COPD events.”39

Weather can be a significant factor that worsens respiratory distress in patients, affecting how they experience their symptoms. Johannson et al31 noted that patients perceived weather (i.e., heat, cold, wind, and moisture) as a barrier to everyday life. Cook et al43 also discussed the effect of weather on breathing:

- "Weather affects me so much…Never know what kind of air there will be. Hot is horrible. Cold is horrible. Humid is even worse. I never commit myself to anything. Most of my friends and family get it that I can’t know until the day because I never know what kind of breathing day [it] will be.”43

Svedaster et al34 also discussed the effects of colder weather:

- "And with me it’s like, shortness of breath on a day-to-day basis, but like the winter, during the winter, I have that sharp tightness in my chest and that wheeziness, so it’s first thing in the morning and at night.”

Although not the primary focus of this study, the ability to cope with and manage COPD symptoms is a crucial aspect of the patient experience. This ability is influenced by factors such as family and social support, the health care system in the patient’s country, and access to care and services, as well as individual characteristics. Avoidance was common when dealing with the challenges of COPD, as well as isolation from social activities. Avoiding triggers, slowing down, and adhering to treatment were common ways patients adapted to the limitations of daily life with COPD.

Discussion

COPD is a complex, heterogeneous, chronic lung condition caused by abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or alveoli (emphysema) that result in persistent, often progressive, respiratory and systemic manifestations, leading to a variety of symptoms and functional impacts. Individual qualitative research studies in COPD offer rich, descriptive data and context-dependent insights into people’s experiences and perspectives. While qualitative research can play an important role in driving new hypotheses to inform clinical research addressing unmet needs, it is often underutilized.47 This metasynthesis integrates findings across 19 individual qualitative studies, further generating an in-depth understanding of the lived health experience that transcends the context-dependent interpretations in independent research.

In COA research, there can be a misalignment between how researchers and patients understand health concepts. Although patient interviews are commonly used to inform the naming of these concepts, the final decision on terminology rests with the research teams. The challenge is that the label assigned to a health concept may not fully represent the language or terminology used by patients to describe their experience; patients’ knowledge of their disease also plays a critical role in the interpretation of health concepts.14 Measuring the wrong health concept in a trial risks negatively impacting the results, which is why involving patients early in the research process and drawing from high-quality patient-driven research is critical. In our metasynthesis, the final set of thematic labels was derived from specific words and phrases in patient quotes that were selected by researchers from the respective publications. Prominent symptoms identified in the metasynthesis include breathlessness/shortness of breath, cough, mucus, wheezing, chest discomfort, sleeping difficulty, tiredness, and weakness. Patients also described major effects on physical activity, emphasizing difficulties with regular activities of daily living. Emotional experiences included feelings of anxiety, frustration, and discouragement.

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to synthesize patient-relevant health concepts in COPD based on empirical qualitative research that can be used to inform measurement in clinical trials. Our findings were in line with other reviews, such as Disler et al,11 who identified the need for better understanding of the condition, the sustained symptom burden these patients face, and the unrelenting psychological impact of living with COPD as critical themes. Similarly, we found that the significant symptom burden, coupled with the inability to perform regular activities of daily living, has a severe impact on social and role functioning and the psychological and emotional health of individuals with COPD. Our findings are also consistent with results from recent large surveys of people with COPD.48,49

The health concepts that we have identified from this metasynthesis should be considered as provisional. While the concepts provide a valuable starting point for subsequent collaborative discussions between researchers and patients, it is important to recognize their limitations. Currently, the generalizability of these health concepts to the COPD population is constrained by the lack of available data on potentially relevant moderating factors that may influence patient perspectives. We found that authors generally focused on narrow research questions, such as a specific disease stage, experience, or effect, with results not generalizable to the broader patient population. Furthermore, a number of articles did not specify disease severity or present results by severity, education, or socioeconomic status, precluding the ability to analyze results by these factors. The effects of these important variables on patient experience warrant further exploration of the patient symptoms and impacts by disease severity (including early and late COPD) and across diverse patient groups (e.g., gender, ethnicity), health statuses (e.g., comorbid conditions), and study designs. We also appreciate that our study selection criteria for the metasynthesis may have excluded studies that identified other relevant health concepts; a follow-up systematic exploration of these excluded studies may, therefore, be warranted. However, unlike a quantitative metasynthesis, the qualitative synthesis aims to identify purposive rather than exhaustive studies that support an interpretive explanation.50

While each symptom described by patients can occur independently, some patients described interactions between symptoms, such as mucus, cough, breathlessness, and tiredness, which affected various aspects of their daily lives. The multidimensional nature of COPD is complex, with symptoms interacting with and fueling one another. A better understanding of the independent and concurrent symptoms, physical activity challenges, social and role functioning, and emotional experiences is needed. These findings align with the first chapter of the European Respiratory Society’s “COPD in the 21st Century” monograph.51 As part of a collaboration between patients living with the disease and patient organizations, breathlessness was identified as a priority for patients and plays a key role in the “symptom-activity-emotions” interactive patient experience.51 Our results support the growing body of qualitative evidence highlighting how physiological aspects of COPD can lead to downstream day-to-day impacts that increase the burden of the disease, particularly emotional changes.36 These insights underscore the profound and multifaceted impact of COPD on patients' lives, emphasizing the need for comprehensive patient-centered approaches in clinical research.

Conclusions

As a critical first step in the COPD Foundation’s PIVOT initiative,5 we have integrated findings from relevant qualitative research studies to develop a provisional thematic representation of meaningful aspects of patients’ health experiences in COPD. The provisional health concepts constructed from this metasynthesis will be refined in collaboration with patient research partners and used in a Delphi study to reach patient consensus on terminology and priorities. The goal is to establish a unified set of patient-inspired health concepts that represent treatment benefits, such as improvements in how patients feel and function in their daily lives. It will be imperative that the patient selection process for these collaborative activities ensures a broad representation of the various patient characteristics that may influence perceptions of disease burden and treatment benefit. This prioritized set of patient-inspired health concepts will serve as a patient-centered framework for identifying meaningful and measurable concepts of interest (“what to measure”) and selecting fit-for-purpose outcome measures (“how to measure”) to demonstrate treatment benefit in COPD clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: All listed authors substantially participated in the creation of the submitted work. AD, KK, and AH contributed to the conception and/or design of the study. AD, KK, and AH were involved in the acquisition of the data, data analysis, and interpretation, and in the writing and revision of this manuscript. All authors have provided final approval for this version to be published.

Other acknowledgments: We would like to extend our appreciation to Nancy Kline Leidy, PhD, Senior Scientific Advisor for PIVOT, who supported the authors with the conceptualization of this work, provided medical expertise, and reviewed the manuscript. We would like to acknowledge the research support provided by the following Thermo Fisher Scientific staff: Cecilia Jimenez-Moreno (previously employed by Thermo Fisher Scientific), who was involved in the study design, abstract screening, and data extraction, and Angelica Jiongco, MSc, and Agkreta Leventi, MSc, who supported the data extraction and synthesis. We would also like to thank Amara Tiebout, BA, from Thermo Fisher Scientific, who edited the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

AD and KK are employed by Thermo Fisher Scientific, which received funding from the COPD Foundation to conduct this research. AH is employed by the COPD Foundation and is the lead of the PIVOT initiative. The PIVOT initiative received unrestricted research grants from the following companies: Apogee Therapeutics Inc. (2024–2025), Chiesi (2023–2025), CSL Behring (2023–2024), GSK (2023–2025), Sanofi (2024–2025), Viatris (2023–2025), and Zambon (2023).