Running Head: Association of Mucus Plugging and BMI in Emphysema

Funding Support: None

Date of Acceptance: September 1, 2025 | Published Online: October 3, 2025

Abbreviations: 6MWT=6-minute walk test; BMI=body mass index; CAT=COPD Assessment Test; CI=confidence interval; COHb=carboxyhemoglobin; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COPDGene®=COPD Genetic Epidemiology study; CT=computed tomography; DLCO=diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; ELVR=endoscopic lung volume reduction; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; RV=residual volume; mMRC=modified Medical Research Council; MPS=mucus plug score; PCO2=partial pressure of carbon dioxide; RV=residual volume; SB=single breath; SD=standard deviation; SPIROMICS=Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study; VC=vital capacity; VC IN=inspiratory vital capacity

Citation: Saccomanno J, Elgeti T, Spiegel S, et al. Association of mucus plugging and body mass index in patients with advanced COPD GOLD stages 3 or 4 with emphysema. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(6): 490-499. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0617

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous condition with increasing prevalence and significant morbidity and mortality, making it one of the leading causes of death worldwide.1 Patients are frequently classified into clinical COPD phenotypes: emphysema and chronic bronchitis. In emphysema, chronic respiratory tract inflammation leads to remodeling and thickening of the airway walls, particularly in the small airways. The resulting airflow trapping in the alveoli worsens during expiration, and the ensuing hyperinflation impairs breathing mechanics, causing dyspnea and exercise intolerance.2-5 In chronic bronchitis, excessive mucus production—resulting from an increase in goblet cell number and dysplasia, expansion of submucosal glands, mucus dysfunction, and impaired mucociliary clearance—results in chronic cough and excessive expectoration.2,6-9 Recently, focus has been directed towards mucus plugs observed on computed tomography (CT) of the chest, which completely occlude the airway lumen, as a potential imaging biomarker. Mucus plugs can be found in up to 57% of COPD patients and are associated with worse lung function and a lower 6-minute walk distance, and may even be present without eliciting symptoms.10,11 Although higher emphysema scores and an increased number of mucus plugs are independently associated with impaired lung function, there may be a significant overlap between the 2 COPD phenotypes. This is particularly relevant, as a higher mucus plug burden has been associated with increased mortality.10,12 Emerging evidence suggests that mucus plug burden is a valuable imaging biomarker for risk assessment in COPD patients.

Impact of mucus burden in patients with advanced COPD and clinically leading emphysema was previously underestimated, even though mucus plugs are present in 25%–76% of patients with COPD.10 Recent publications drastically underlined that patients with COPD and high mucus burden had worse functional outcomes and increased mortality without eliciting more symptoms. Additionally, a lower body mass index (BMI), a simple clinical parameter to assess body adiposity, seemed to be associated with a higher mucus burden.10-12 Interestingly, a lower BMI has been associated with increased mortality in COPD patients, as well.13

Among COPD patients undergoing endoscopic lung volume reduction (ELVR) therapy with valves, despite advanced emphysema, there might be a subgroup with mucus plugging that is particularly vulnerable and has a worse overall prognosis.

The aim of this study was to investigate the presence of mucus plugging and its impact on patients with emphysema presenting for ELVR. Therefore, we evaluated mucus plugs on CT scans of the thorax and linked it with baseline characteristics, such as BMI, lung function parameters, exercise capacity, and quality-of-life parameters in this well-defined cohort of emphysema patients.

Material and Methods

Data Acquisition

Data were obtained from patients with advanced COPD who presented for evaluation of lung volume reduction therapy at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Patients were assessed according to the standards of the emphysema registry. The emphysema registry14 is a German national open-label, noninterventional, multicenter trial. The research presented in this article was conducted according to the standards of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and the appropriate guidelines for human studies. All data were derived from prospective open-label clinical studies in our institution which were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany (EA2/149/17 and EA1/136/13). All patients consented to participation. Inability to sign the consent form was an exclusion criterion. Data were acquired from individual patient files and via REDCap electronic data capture tools managed by CAPNetz.15

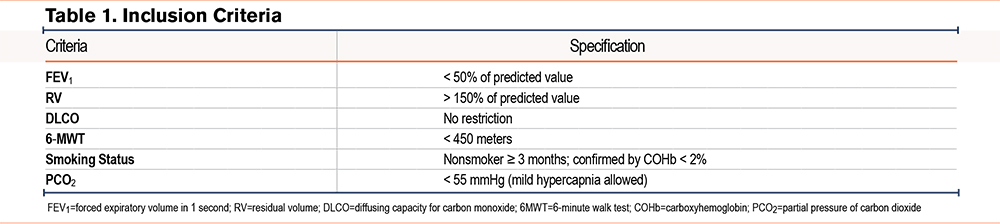

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria, as defined by the emphysema registry standards, were described in detail previously16-20 and are presented in Table 1. Patients with advanced COPD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD]21 stages 3 and 4), a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of <50%, and a residual volume (RV) of >150% were included. There were no restrictions regarding diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) had to be <450m. All patients were required to be nonsmokers for at least 3 months, as documented by a carboxyhemoglobin level of <2%. Mild hypercapnia (partial pressure of carbon dioxide [PCO2] <55mmHg) was acceptable; otherwise, patients were evaluated for noninvasive ventilation therapy. Additionally, all patients received optimal medical treatment for their COPD and participated in a structured exercise program for respiratory diseases either before or after lung volume reduction therapy. Patient symptoms had to be primarily attributed to emphysema, with dyspnea as the lead symptom and without chronic cough and sputum production.

Study Population

Patients included in this study were evaluated at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin for interventional or surgical treatment of advanced COPD and subsequently underwent therapy. Eligibility and treatment recommendations were determined by the local emphysema board, a multidisciplinary team comprising interventional pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, and radiologists.

Evaluation Procedure

Patients underwent a standardized evaluation procedure. To calculate the BMI, the patient´s weight in kilograms was divided by the square of their height in meters (kg/m²). Lung function parameters were measured using spirometry, body plethysmography, and diffusion tests (Power Cube+, Ganshorn Medizin Electronic GmbH; Niederlauer, Germany). A 6MWT, capillary blood gas analysis, measurement of COHb, and echocardiography were also performed. Baseline symptom burden was assessed using the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale. All patients received a CT scan of the thorax in inspiration without contrast media, along with a software-based quantification of emphysema destruction per lobe and an assessment of fissure integrity with StratX (PulmonX Inc.; Redwood City, California). To quantify emphysematous destruction, the number of low-density voxels (≤ -950 Hounsfield units) was summed to calculate the emphysema score for each lung lobe. In most cases, lung volume reduction therapy targets the lobe with the highest emphysema score. Accordingly, this target lobe is documented in the REDCap database, along with the heterogeneity index, which quantifies the difference in emphysema scores between the target lobe and its adjacent lobe. To evaluate collateral ventilation per lobe with the Chartis® assessment system (PulmonX Inc.; Redwood City, California), all patients with intermediate fissure integrity underwent bronchoscopy under procedural sedation with propofol and midazolam, either using high-frequency jet ventilation or while breathing spontaneously.22-24

Assessment of Mucus Plug Score

A retrospective analysis of all baseline CT scans was performed by 2 expert radiologists (AP and TE with 5 and >15 years of experience) to assess mucus plug burden. For each case, mucus plug burden was quantified using a bronchopulmonary scoring system previously described by Dunican et al.10,25 Soft-tissue thin-slice reconstructions were evaluated using the multiplanar reconstruction tool of the clinical imaging viewer (Visage® 7 version 7,.2, Visage Imaging GmbH; Berlin, Germany). A lung window (level -550 HU, width 1600 HU) was used.

One point was scored for every pulmonary segment with at least 1 mucus plug, resulting in a maximum score of 20 points. A mucus plug was defined as an opacification that completely occludes the airway. In the most peripheral 2 centimeters of lung parenchyma, the bronchial diameter was too small to detect mucus plugs. CT scans were categorized by MPS as suggested by Diaz et al12: 0, 1, 2, and ≥3.

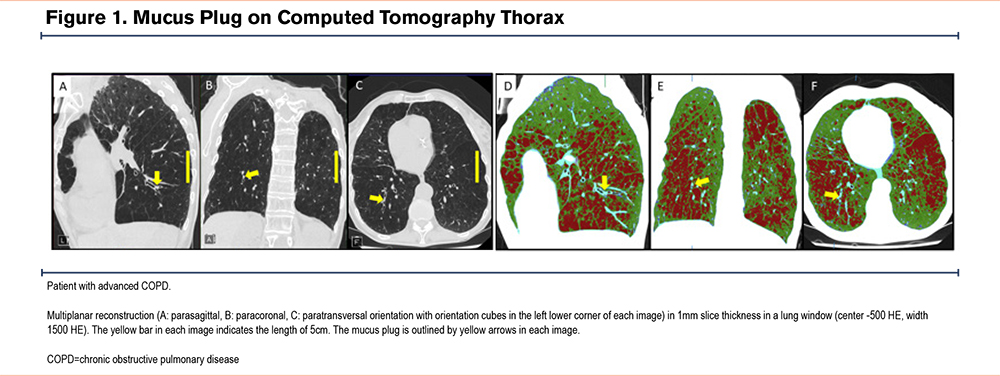

An example of a typical mucus plug is shown in Figure 1 (A-C). For visualization of concomitant emphysema the corresponding areas are coded in red in the second half of Figure 1 (D-F).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were summarized using absolute and relative frequencies for each level. Continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations. Comparisons between subgroups, defined by patient characteristics, were conducted using analysis of variance, followed by independent sample t-tests for pairwise comparisons and chi-quadrat test. Interrater reliability was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha. To examine the relationship between an ordinal outcome and independent variables, an ordinal logistic regression analysis was performed. Two separate ordinal logistic regression models were constructed. The first included the covariates: gender, age, BMI, emphysema in the target lobe (%), FEV1 (%), and 6MWT (m). The second model excluded emphysema and included: gender, age, BMI, FEV1 (%), and 6MWT (m). As no adjustment for multiple comparisons was applied, all p-values should be considered exploratory. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 24.0.0.0, IBM; Armonk, New York).

Results

Patient Characteristics

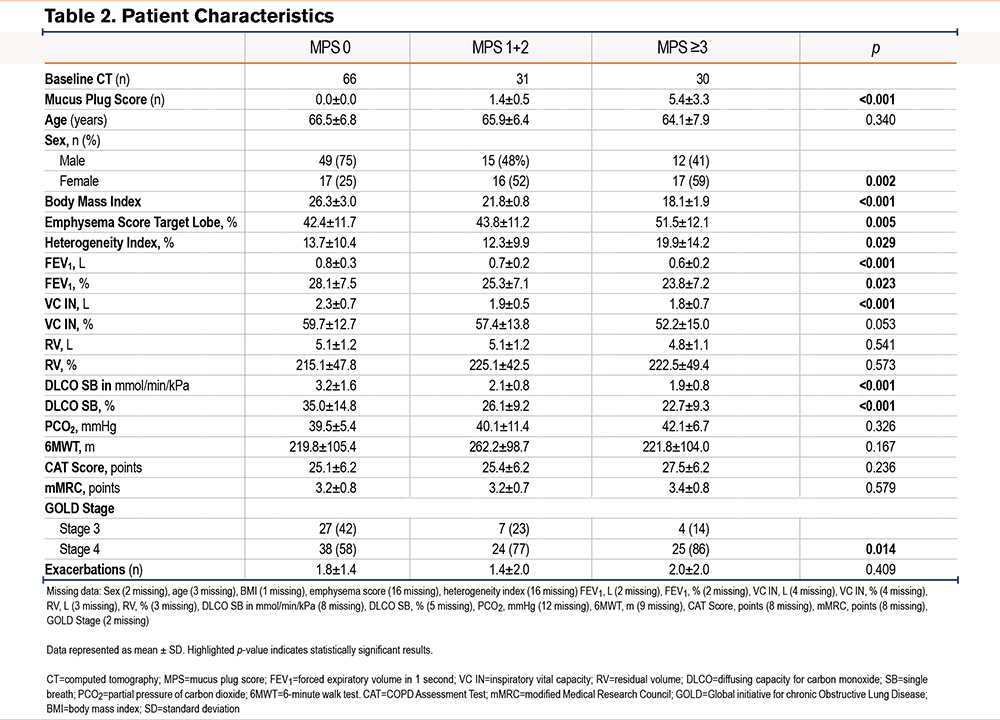

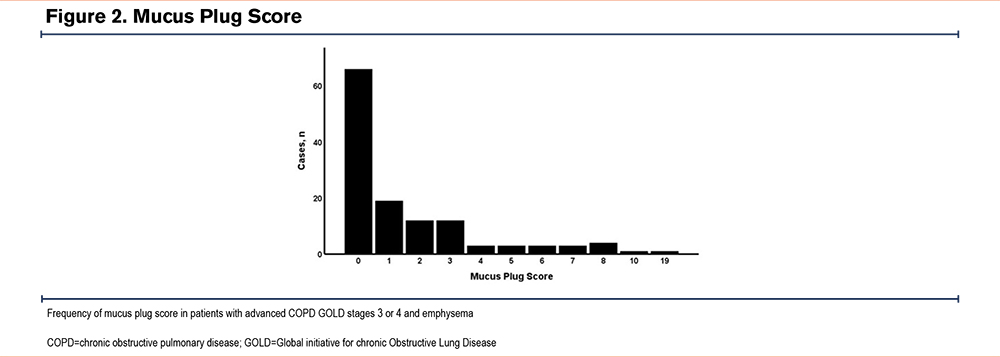

Table 2 displays patient parameters of 127 patients who underwent ELVR. In 66 cases, the MPS was 0, in 31 cases there was an intermediate MPS of 1 or 2, and in the remaining 29 cases an MPS of ≥3 was detected (Figure 2). All patients had COPD GOLD stages 3 or 4 (GOLD stage 3 n=38 [31%] versus GOLD stage 4 n=87 [69%]). In patients with an MPS of 0, 42% had GOLD stage 3 and 58% had GOLD stage 4. With increasing MPSs, more patients had GOLD stage 4 airflow obstruction, with only 14% having GOLD stage 3, and 86% having GOLD stage 4 in the case of MPSs ≥3 (p=0.014).

Age range was comparable among the groups. With increasing mucus burden, BMI decreased (p<0.001). There were significant differences in gender distribution with an almost similar distribution in patients with a MPS of 1 to 2 and ≥3. In patients with an MPS of 0, 25% were female and 75% were male (p=0.002).

Interobserver Variability

To determine interobserver variability of the 20 CT scans that were independently scored by 2 experienced thoracic radiologists, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated. It showed an excellent agreement between the 2 radiologists with an alpha of 0.955.

Emphysema Score

Emphysema score of the target lobe and difference and heterogeneity index between the target lobe and its adjacent lobe did increase with increasing MPS (p=0.005 and p=0.029 respectively), as displayed in Table 2.

Lung Function Test Parameters, Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide, and 6-Minute Walk Test

Table 2 shows statistically significant differences in FEV1 (relative, p=0.023; absolute, p<0.001), vital capacity (VC) (absolute, p<0.001), and DLCO (absolute and relative, p<0.001) with increasing mucus burden. No difference in relative VC, absolute and relative RV, PCO2, and 6MWT was noted between the groups.

Quality of Life Parameters

No association of CAT score or mMRC with increasing mucus plug burden was detected (Table 2).

Additional Parameters

In regard to COPD exacerbations over the past 12 months, there was no difference between the groups. When comparing the GOLD stages of the 3 groups, patients with more mucus plugs had more advanced GOLD stages (p=0.014) (Table 2).

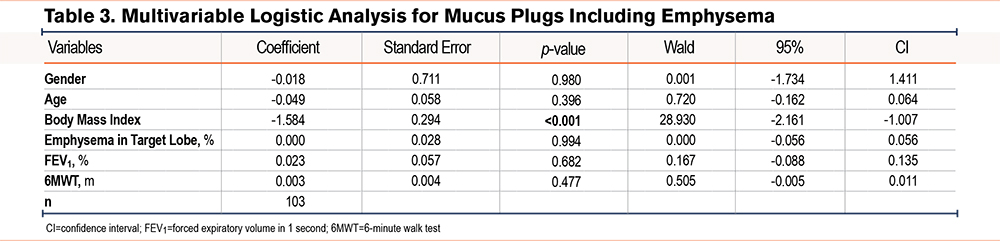

Body Mass Index, Emphysema, Lung Function, and Mucus Burden

To detect associations between mucus burden and patient characteristics, we examined a logistic ordinal regression model and included the following variables: age, gender, BMI, emphysema in target lobe (%), FEV1 (%), and 6MWT (m) (Table 3). A statistically significant association between mucus burden and BMI was detected, showing that a decrease in BMI was associated with a higher mucus burden (p<0.001; coefficient of -1.584).

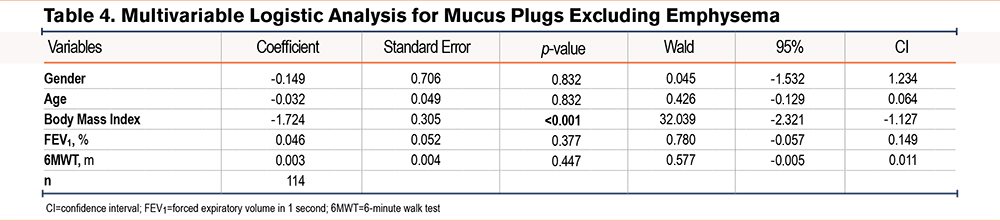

Body Mass Index, Lung Function, and Mucus Burden

To account for a possible interaction between emphysema and BMI, we repeated the logistic ordinal regression model excluding emphysema in the target lobe (Table 4). The statistically significant association between mucus burden and BMI remained, showing that a decrease in BMI was associated with a higher mucus burden (p<0.001; coefficient of -1.724).

Discussion

This is a novel analysis focusing on the impact of mucus burden in patients with advanced COPD and emphysema, a highly symptomatic and vulnerable patient population. Our results showed that patients with a higher MPS had worse pulmonary function parameters and more advanced emphysema on emphysema quantification, without affecting life quality parameters. Interestingly, a decrease in BMI was associated with a higher mucus burden.

A strong association between lower FEV1 and lower BMI in COPD patients—linked to increased mortality—has been previously described.26 In our analysis, we observed an association between mucus burden and BMI in the regression models, both with and without adjustment for the emphysema score of the target lobe. Multiple mechanisms have been suggested for this relationship, including increased resting energy expenditure, nonrespiratory skeletal muscle atrophy due to reduced peripheral oxygen supply, and systemic inflammation.27-30 Furthermore, the recent publication by Diaz et al reported an overall decline in lung function parameters, higher emphysema scores, and lower BMI with increasing mucus burden, along with a higher risk of mortality in patients with a high mucus burden.12 Our study similarly demonstrates a decline in lung function parameters and BMI with increasing mucus burden in a cohort of patients with very advanced emphysema. Importantly, our results also reveal a novel finding: a strong association between BMI and mucus burden, both of which serve as indicators of increased mortality in COPD.

The MPS is a helpful and reproducible radiological biomarker in quantifying mucus plugs in medium-to-large sized airways demonstrated by an almost perfect agreement in our analysis, which is in line with previous publications.10,25 In our study, the distribution of mucus burden was similar to that reported by Diaz et al from the COPD Genetic Epidemiology (COPDGene®) study cohort: approximately 50% of cases exhibited low MPSs (0), about 25% showed intermediate scores (1–2), and roughly 25% demonstrated high scores (≥3). In the COPDGene study, around 40% of patients were active smokers.12 In contrast, among participants from the Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study (SPIROMICS) cohort reported by Dunican et al, a very high MPS (≥5) was observed in 50%–60% of patients with severe COPD (GOLD stages 3 or 4). Notably, in the SPIROMICS cohort, 17.8% of patients with GOLD stage 4 and 30.1% of those with GOLD stage 3 were current smokers. Dunican et al also found that a higher MPS was associated with smoking and that mucus plugs and emphysema had a similar impact on airflow obstruction (FEV1) and resting hypoxemia.10 In the mucus plug study by Dunican et al,10 400 patients with COPD across all GOLD stages and 20 never-smokers were included. Although the majority of cases were COPD GOLD stage 3 (51%) and stage 4 (15%), the remaining 34% comprised patients with COPD GOLD stages 1 and 2. Similarly, the larger patient cohort from Diaz et al12 (n=4363) included all stages of COPD irrespective of clinical phenotype—specifically, 72% of patients had COPD GOLD stages 1 and 2, 20% had GOLD stage 3, and 8% had GOLD stage 4. In contrast, our study population consisted exclusively of nonsmokers with advanced COPD (GOLD stages 3 and 4) and the clinical subtype of emphysema, with approximately one-third of patients having COPD GOLD stage 3 and two-thirds having COPD GOLD stage 4. Dunican et al10 report a higher degree of mucus plugging than Diaz, whose findings align with ours. It remains unclear whether the lower mucus plugging observed in our study is due to the inclusion of only nonsmokers or a selection bias, as we included only patients with clinically predominant emphysema.

Furthermore, more advanced stages of COPD in our study were associated with overall worse lung function parameters compared to those reported in other studies. Consistent with previous publications, a higher mucus burden was strongly correlated with lower FEV1, VC, and DLCO.10,12 Notably, no differences in RV were observed among the 3 groups, even though both the emphysema score in the target lobe and the heterogeneity index increased with a higher mucus burden. This suggests that quantitative emphysema measures may more precisely characterize differences in patients with advanced COPD and emphysema than RV alone. The data showed a higher heterogeneity index in patients with greater mucus burden. While the underlying reason is not entirely clear, this finding likely reflects more extensive emphysema and more severely impaired lung function in this patient group. Additionally, there were no differences in the 6MWT and PCO2 between the groups in our study. While previous studies have demonstrated an association between mucus burden and 6MWT performance, our data did not replicate these findings. The most likely explanation is that our study population consisted exclusively of patients with very advanced stages of COPD, potentially limiting the variability in exercise capacity.12,25

Symptoms reported by the CAT score and mMRC were comparable in all 3 groups, highlighting the observation that an increase in mucus plugs does not correlate with an increase in mucus burden.11

These findings suggest that the MPS should be used to evaluate patients with advanced emphysema presenting for lung volume reduction therapy for individual risk stratification. Additionally, our results support that these patients might benefit from airway clearance techniques and inhaled mucokinetic or mucolytic therapies such as hypertonic saline or novel reducing agents that are currently in clinical testing for COPD.31,32

The main limitations of this study are its retrospective monocentric design and the relatively small sample size. However, by focusing exclusively on patients with advanced COPD and emphysema, the study provides a detailed overview of mucus burden in this specific patient group. Unfortunately, our data does not show to what extent mucus plugs influence lung volume reduction therapies, such as ELVR therapy with valves. More research is needed to elucidate these questions.

This study demonstrates that high mucus burden is present in patients with advanced emphysema—a subgroup of patients with COPD in which its impact may have been previously underestimated. Our data also corroborate previous findings that mucus plugs are associated with worse lung function parameters due to increased airflow obstruction. Notably, this is the first study to link a higher MPS with a lower BMI. This observation is particularly relevant given recent findings associating higher mucus burden with increased mortality, and that lower FEV1 and lower BMI are both independent risk factors for mortality in COPD patients. Furthermore, it highlights the heterogeneity of COPD and the significant overlap between emphysema and chronic bronchitis, 2 clinical entities once considered distinct. These findings underscore the need to explore novel treatment strategies to target mucus plugging for personalized, risk‐stratified management of patients with advanced COPD and emphysema. Our results also raise the question of whether mucus burden should be routinely evaluated in all patients with advanced COPD and emphysema presenting for lung volume reduction therapy.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: JS and TE drafted the work and conducted the literature research. JS, TE, SS, EP, TS, AP, MAM, MW, and R-HH are responsible for data interpretation, manuscript writing, and critically revising the manuscript. KN provided statistical analysis and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave approval of the final version to be published.

Data availability statement: Data can be made available by request to the corresponding author.

Other acknowledgments: The authors sincerely thank CAP NETZ, the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH), and Lungenemphysem Register e.V., for data management and Laura Grebe and Andreas Hetay for editing support.

ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used to assist with language refinement and grammar to improve the readability of the manuscript. AI was not used to generate content. The authors reviewed and approved all AI-assisted content.

Declaration of Interests

JS reports presenter fees by PulmonX, training and travel support by Medtronic, and travel support by Astra Zeneca. He is member of the scientific board of the German Lung Emphysema Registry. MAM was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (CRC 1449 – project 431232613) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (82DZL009C1 and 01GL2401A). MW was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (CRC 1449, project ID 431232613, subproject B02), the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research in the framework of e:Med SYMPATH (01ZX2206A, 01ZX1906A), NUM-NAPKON (01KX2121, 01KX2021), CAP-TSD (031L0286B), and by the German Center for Lung Research (DZL) (82DZLJ19C1). RHH reports payment or honoraria for lectures and presentations by Pulmonx, Astra Zeneca, GSK, Berlin Chemie, Olympus, Chiesi GmbH, and travel support by Pulmonx, Astra Zeneca, GSK, Berlin Chemie, Olympus, Chiesi GmbH. He is head of the German Lung Emphysema Registry. TE, SS, EP, TS, AP, and KN report no conflict of interest with the current manuscript.