Running Head: Sex-Associated Differences in NTM Infection

Funding Support: This work was supported by the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) CF Research Center Pilot Grant (CM) under the UAB Research and Development Program from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation – ROWE19RO (DAVIS).

Date of Acceptance: September 17, 2025 | Published online date: October 3, 2025

Abbreviations: ATS=American Thoracic Society; BMI=body mass index; CF=cystic fibrosis; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT=computed tomography; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1%pred=forced expiratory volume in 1 second percentage predicted; GERD=gastroesophageal reflux disease; IDSA=Infectious Diseases Society of America; ILD=interstitial lung disease; MAC=Mycobacterium avium complex; NTM=nontuberculous mycobacteria; NTM-PD=NTM pulmonary disease; PA/A=pulmonary artery to aorta; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus

Citation: Garcia B, Mullins M, Lim L, Henostroza G, Margaroli C. Sex-associated radiographic and clinical differences in nontuberculous mycobacteria pulmonary disease. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(6): 455-465. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0622

Introduction

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are environmentally ubiquitous organisms, commonly isolated from water and soil environments, and have become a global health care challenge with the frequency and incidence of NTM infections steadily increasing worldwide.1 In the United States, NTM incidence increased2,3 from 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1980s, to 47 cases per 100,000 in 2007. Similar trends have been observed in Europe, Asia, and Australia.1,4 The increased incidence of NTM infections is attributed to several factors including HIV, increased use of iatrogenic immunosuppression, an aging cohort that encompasses a larger component of the general population, increased recognition on chest imaging, and improved culture methodology. Interestingly, regional differences in NTM patient demographics are apparent. For example, in eastern Asia, the majority of patients with NTM-pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) are males (79%) with 37% of them presenting with post-tuberculosis lung disease,5 whereas in the United States, NTM-PD has been associated with postmenopausal White females with slender build and skeletal abnormalities, including scoliosis and pectus excavatum. Many of these individuals have no pre-existing immunodeficiency or smoking history, and this disease phenotype has been termed “the Lady Windermere syndrome.”6

NTM pulmonary infections can be caused by different mycobacteria. Infections worldwide are predominantly caused by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) (47% of total infections worldwide),7 however, geographical differences are present even within the same continent. In eastern Asia, MAC is most commonly isolated in Japan, India, Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand, and South Korea, while in China and Hong Kong, M.chelonae and M.gordonae are the predominant NTM species isolated.5 In the United States, regional geographic variances have also been observed, which could be, at least in part, attributed to the variety of environmental conditions in the United States. As an example, although MAC is the most commonly identified species causing NTM-PD in the United States, M. abscessus subspecies is responsible for as much as 31.8% of NTM-PD in the state of Florida, highlighting the heterogeneity of this disease within the same country.1

The heterogeneity of disease severity caused by NTM infections is not fully explained by etiology or microbiology alone. As an example, approximately 45% of patients with NTM isolated from the airway will not initially require treatment at the time of first isolation and guidelines for which individuals should be treated exist.8-12 In addition to disease heterogeneity, striking differences in treatment efficacy and disease course are present in this patient population, with some individuals presenting with MAC infection achieving a sustained culture conversion following 18 months of oral antibiotics, while others will suffer from chronic recalcitrant infections requiring a combination of oral, inhaled, and intravenous antibiotics for life.13

A variety of pre-existing risk factors for the acquisition of NTM species and the development of subsequent pulmonary disease have been described. In the case of individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF) and primary ciliary dyskinesia, monogenetic mutations have been identified and are critically important risk factors in the development of NTM infections. However, only a small subset of individuals suffering from CF or primary ciliary dyskinesia will go on to acquire NTM infections14,15 suggesting that for these individuals, additional risk factors exist and may include environmental exposures, pre-existing lung disease severity, age, and sex. Most individuals with NTM-PD in the United States, however, do not have a monogenetic disease that provides an explanation for the development of NTM-PD, and, according to the American Lung Association, more than 86,000 individuals are estimated to have NTM-PD in the United States.16 For these individuals, a broad spectrum of risk factors have been identified and include chronic immunosuppression and underlying structural lung remodeling due to non-CF bronchiectasis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), prior tobacco abuse, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).17,18 However, while COPD is a common comorbidity in NTM-PD, association of smoking with NTM infection remains unclear, and, similarly, only a small subset of current and former smokers will go on to acquire NTM infections of the lung.

Previous studies have sought to radiographically phenotype cohorts of NTM-PD patients19-21 and a formal staging or scoring system for NTM-PD severity using chest imaging does not currently exist. At present, NTM-PD is generally described radiographically as either “nodular-bronchiectatic” or “cavitary.”22-25 In a systematic review, NTM-PD was shown to have a 5-year rate of mortality of 27% in Europe, 35% in the United States, and 33% in Asia, with male sex, presence of comorbidities, and fibro-cavitary disease predicting high mortality.26 Further, culture conversion rates in NTM-PD tend to be higher in the nodular-bronchiectatic disease compared to the fibro-cavitary form.12,27,28 Nevertheless, these studies have yet to assess radiographic sex-based differences in NTM-PD, which given the female sex predisposition in the United States towards acquiring this infection, may provide insight into the differing risk factors and disease severity seen across sexes. This knowledge gap prevents a clearer understanding of the interplay between NTM pulmonary pathophysiology and concomitant pulmonary diseases, which may necessitate additional therapies for some individuals and suggest potential risk factors for the acquisition of NTM infections. Here, we report a single center, cross-sectional retrospective study of our patient registry, highlighting radiographic differences by sex amongst people affected by NTM-PD. These results build upon the pre-existing literature towards a broader understanding of sex differences in radiographic findings on NTM-PD globally.

Methods

Clinical data were obtained retrospectively (the University of Alabama, Bronchiectasis Research Registry, institutional review board Project Number: IRB-300010437) for patients seen at a large academic NTM care center in the southeastern United States. Patients with CF were excluded from this retrospective collection. Data was collected in October 2024 for 191 patients. A total of 10 were excluded as they presented with skin and soft tissue infection, and 181 were identified as having pulmonary infections and were used in the analysis. Clinical data included demographics (age, sex, race), body mass index (BMI), smoking history, forced expiratory volume in 1 second percentage predicted (FEV1%pred), microbiological profiling of sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage, treatment history, evidence of culture conversion or refractory disease, and comorbidities associated with NTM infection (bronchiectasis, GERD, COPD, emphysema, rheumatologic disease, interstitial lung disease, lung cancer, and other nonlung malignancies), evidence of pectus excavatum, hiatal hernia, or scoliosis.

Chest computed tomography (CT) scans were obtained from the most recent visit and were reviewed by a board-certified pulmonologist and an infectious disease specialist who serve as codirectors of the NTM care center. The physicians were blinded to patients’ clinical outcomes. Assessment of radiographic features was performed by both specialists independently for all 181 CT scans. The chest CT closest in time to the start of the study period was used for the analysis. All chest CTs were performed for routine clinical purposes, and there was not a standardized method for imaging acquisition including variability in slice thickness, and some individuals had high resolution CT scans that included inspiratory and expiratory images while others had standard chest CT's performed. The clinicians reviewed chest imaging independent of each other and used a standardized template to manage data collection. The template separated the lungs by lobe, including a section for the lingula, with each lobe being assessed for the following: bronchiectasis, presence of cavitary lesions, fibrosis, emphysema, tree-in-bud changes, atelectasis, nodules, lobectomy, ground glass opacity, and consolidation. Each lobe was scored using the modified Reiff scoring system.29 Imaging data that was obtained was then reviewed in tandem by the clinicians for each individual's chest CT, and, when differences between clinicians was identified, the clinicians rereviewed that participant’s imaging and reached a decision by consensus. NTM-PD (symptomatic) was defined per the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) criteria11 as presence of disease on CT scan (with or without cavitation), 2 or more positive sputum cultures or one bronchoalveolar lavage culture for an NTM species, and presence of active significant symptoms attributed to NTM infection. Statistical analysis of sex-associated differences were performed in JMP Pro® v18 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, North Carolina) using ChiSquare test, Fisher’s exact 2-Tail test, and Wilcoxon rank sum test as indicated.

Results

Study Cohort

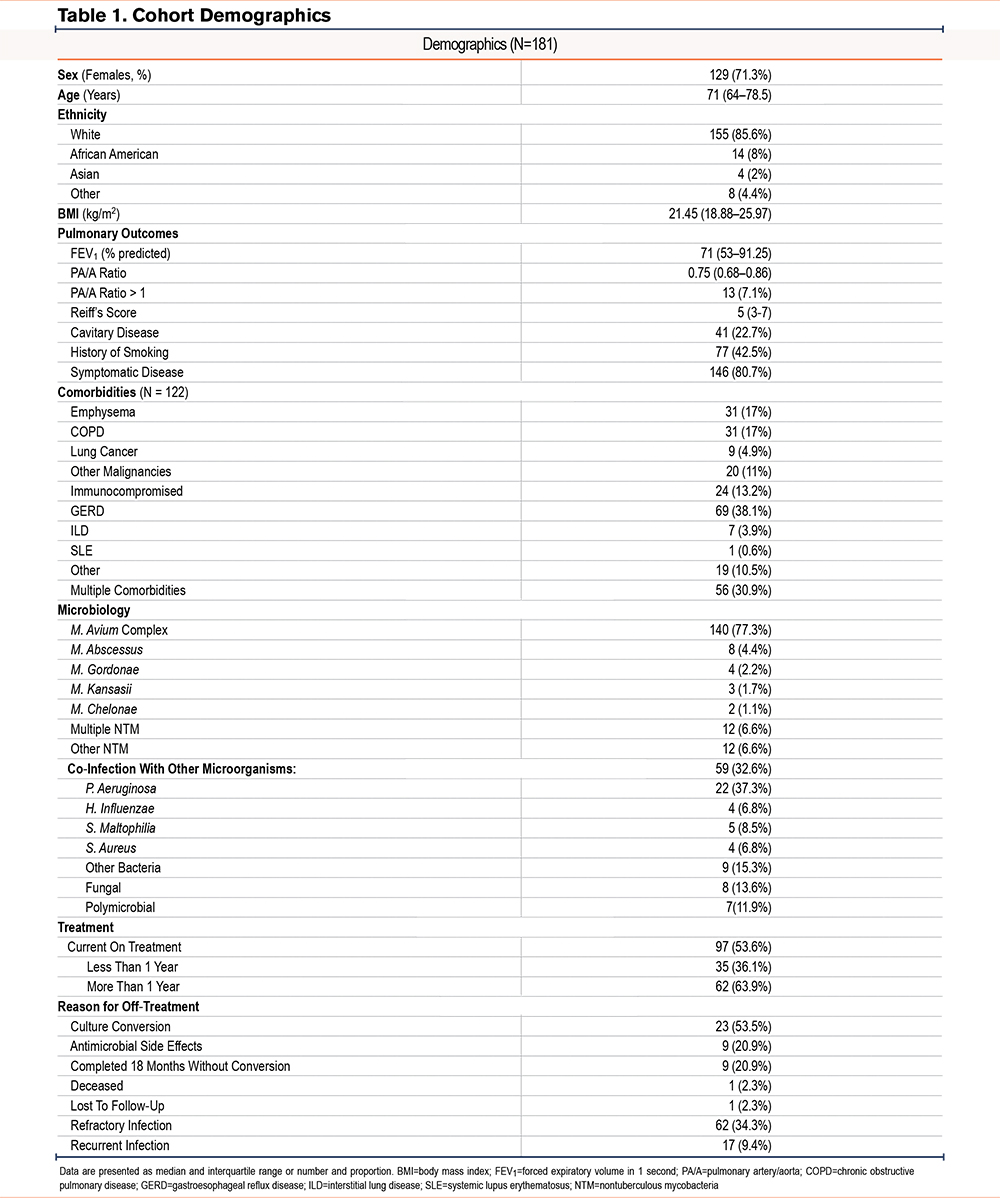

A total of 181 patients were identified as having an NTM isolate from the airway (Table 1). Of these, 129 individuals (71.3%) were female, and the median age was 71 years. In line with the previously reported features of NTM-PD patients in the United States, our cohort was predominantly White (85.6%) and 77.3% of individuals were infected with MAC. The median FEV1%pred was 71%, the median modified Reiff score was 5, and the pulmonary artery to aorta ratio (PA/A ratio) was abnormal in 13 patients (7.1%). Of the 181 patients identified, 146 (80.7%) were diagnosed as having active NTM-PD defined using the ATS/IDSA criteria, of which 41 individuals (22.7%) had radiographic evidence of cavitary disease on their CT scan, and 77 (42.5%) reported a history of smoking.

Comorbidities commonly associated with NTM infection were reported for 122 individuals, with GERD being the most common (38.1%), followed by emphysema (17%), and COPD (17%), and 13.2% of patients were on immunosuppressant therapies for other comorbid conditions. A total of 30.9% of individuals reported 2 or more comorbid conditions associated with NTM-PD.

NTM infections were predominantly caused by MAC (77.3%) followed by M. abscessus (4.4%), while 12 individuals (6.6%) presented with multiple NTM species. Further, co-infections with other microorganisms were present in 32.6% of individuals, with P. aeruginosa co-infection being the most common (37.3%). Additionally, 13.6% of individuals had fungal species isolated from the airway, and 11.9% of individuals had polymicrobial co-infections with 2 or more microorganisms detected in addition to NTM.

Regarding treatment regimen, drug sensitivity profiles were available for 82 patients. Of the patients included in this study, 97 (53.6%) were on treatment, of which 14 patients were on inhaled antibiotics (7.7%) and 10 patients were actively receiving intravenous antibiotic treatment (5.5%). A total of 13 patients showed resistance to macrolides (13.9%), 49 patients to moxifloxacin (27.1%), 49 patients to linezolid (27.1%), 7 to amikacin (3.8%), and 18 to tetracyclines (9.9%). Further, 50 of the 64 (78.1%) presented with resistance to 2 or more antibiotics, and 62 patients (34.3%) presented with treatment refractory infections defined as persistently positive cultures despite greater than 6 months of a multidrug regimen.

Sex Differences in Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Pulmonary Disease

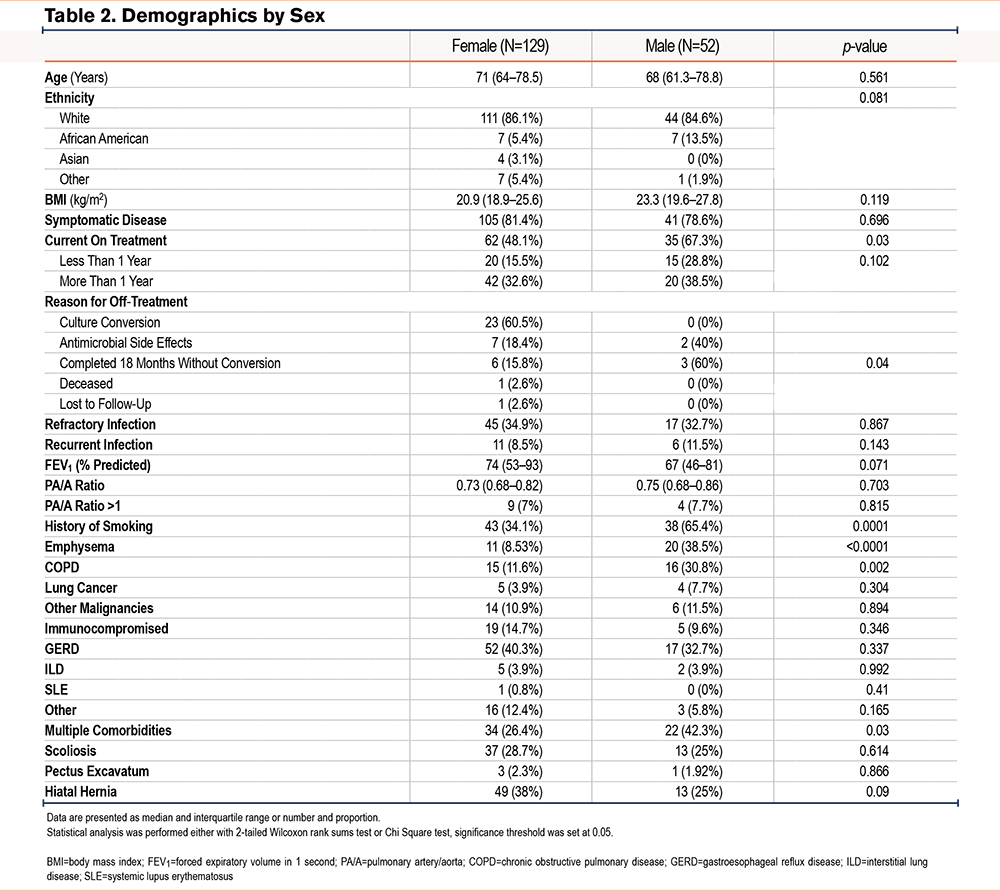

Male and female patients were demographically similar and did not significantly differ in median age (males 68 years versus females 71 years), BMI (23.9kg/m2 male versus 22.4kg/m2 female), number of comorbidities, FEV1%pred, PA/A ratio, Reiff’s score, or frequency of symptomatic pulmonary disease (males 78.8% versus females 81.4%) (Table 2). Both cohorts were predominantly White race (84.6% males, 86% females), however, African Americans represented 13.5% of the male cohort compared to 5.4% in the female group. While the number of comorbidities did not differ between the 2 cohorts, men were more likely to present with a history of smoking (65.4% male versus 34.1% female, p=0.0001), emphysema (38.5% male versus 8.53% female, p<0.0001), and COPD (30.8% male versus 11.6% female, p=0.002), while women presented more frequently with hiatal hernia although statistical significance was not met (38% female versus 25% male, p=0.06).

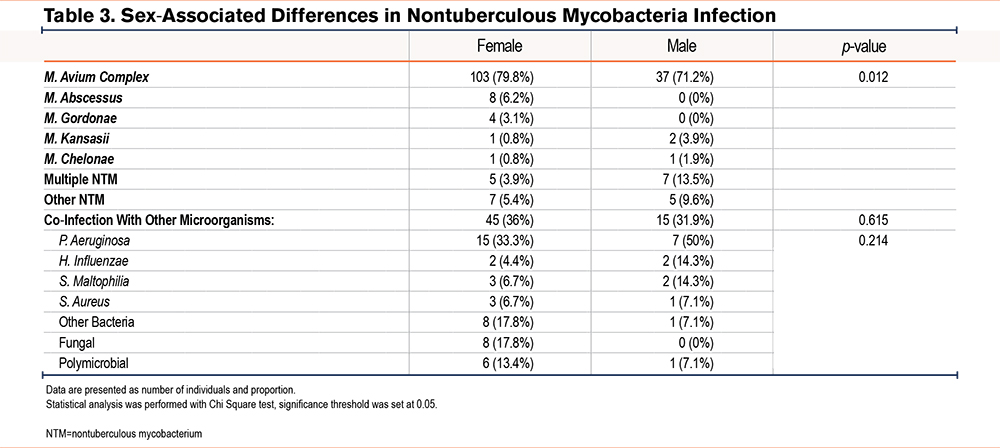

Although most infections were caused by MAC in both males and females, females had a higher rate of infections caused by M. abscessus (6.2% versus 0%), while males were more prone to present with multiple and concurrent species of NTM (3.9% versus 13.5%, p=0.012) (Table 3). Additionally, while no significant difference was observed in how many patients experienced co-infections (36% female and 31.9% male), correspondence analysis of co-infections with other microorganisms showed that fungal infections and polymicrobial infections were more common in females while co-infection with P. aeruginosa was more common in males. Interestingly, presence of co-infection in females was significantly associated with refractory NTM infection (p=0.0003), while this difference was not observed in the male group.

Lastly, no significant difference was observed in our cohort between males and females in the development of resistance to antibiotics, as females and males showed a frequency of resistance to antibiotics of 35% and 37%, respectively. Likewise, we found no difference in resistance based on smoking status. However, male patients were more likely to undergo treatment with intravenous antibiotics (13.5% versus 2.33%, p=0.007) and to have a treatment regimen with 2 or more concurrent antibiotics (59.6% males versus 42.6% females, p=0.03). Further, despite treatment regimen, male patients were less likely to have previously achieved culture conversion compared to females, independent of smoking history, and were more likely to have received treatment durations in excess of 1 year at the time of data collection (67.3% versus 48.1%, p=0.003). This finding remained even in the absence of a history of smoking (66.67% versus 45.78%) (Table 2).

Radiographic Sex-Associated Differences in Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Pulmonary Disease

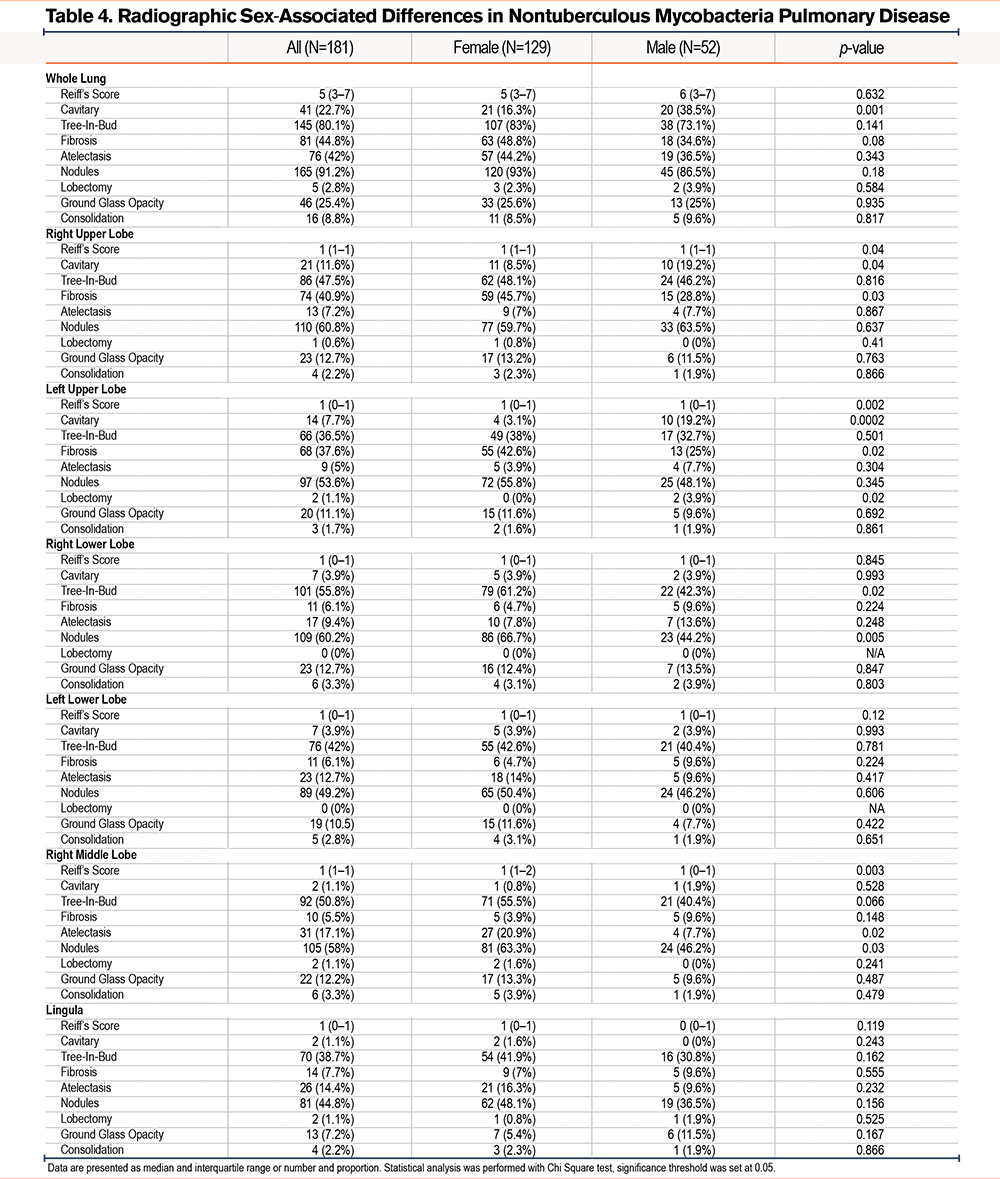

Radiographic analysis of CT scans demonstrated bronchiectasis in all individuals, however, men were more likely to have cavitary disease (38.5% males versus 16.3% females, p=0.001, Table 4). Females with NTM had higher rates of upper lobe predominant fibrotic changes (right upper lobe: 45.7% females versus 28.8% males, p=0.02; left upper lobe: 42.6% females versus 25% males, p=0.03), tree-in-bud patterns (right lower lobe: 61.2% females versus 42.3% males, p=0.02) and nodules (right lower lobe: 66.7% females versus 44.2% males, p=0.005) in the lower lobes.

Given the known relationship of exposure to cigarette smoke with chronic inflammation and airway remodeling, which can include the development of bronchiectasis, we also investigated whether a history of smoking could be influencing the presence of cavitary disease in both cohorts. Interestingly, males were more likely to experience cavitary disease than females independently of their history of smoking, suggesting that additional mechanisms are potentially participating in the process of tissue remodeling based on sex.

Discussion

Female sex has long been recognized as a risk factor for the development of NTM-PD in the U.S. cohort, however, sex-associated differences in clinical and radiographic patterns remains poorly understood. Analysis of our patient registry has demonstrated key differences between sexes in the radiographic features of individuals with NTM isolated from the airways. Our study complements and expands upon a previous report of sex-based differences in the development of bronchiectasis in NTM-PD.30 Indeed, while the cohort in this study is highly similar to the cohort presented in the study by Ku et al,30 our results identified key differences in presence of structural lung disease, including cavitary lesions, as well as differences in co-infection and refractory disease. Further, we observed that presence of co-infection in females was significantly associated with refractory NTM infection highlighting the need to better define changes in the airway microbiome related to the structural and microbiological changes related to the underlying lung disease,31-33 as well as following NTM infection, as it could affect the efficacy of treatment regimens.34

Likewise, our study shows that nodules were identified in more than 90% of patients in our cohort, highlighting that screening for NTM infection in patients that present with these radiographic features may lead to more rapid diagnosis for patients. Further, several studies in NTM infection have utilized different scoring systems to quantify lung disease. Here, we selected the modified Reiff’s score as a metric for lung disease, as it provides a quantitative assessment of the overall geographic severity of bronchiectasis by lobe and also seeks to quantify the severity of bronchiectasis within each lobe (tubular, varicose, cystic). However, given the heterogeneity in the patient population, underlying lung diseases, other predisposing factors, as well as current unknowns in the etiology and progression of NTM-PD, these factors should be considered when more sensitive scoring systems will be developed for NTM-PD.

Presence of apical fibrosis was remarkably common among females with NTM and has not previously been described in association with NTM-PD. These patients did not receive antifibrotic therapies, as these changes were felt to be secondary to chronic infection as opposed to an interstitial lung disease although the relationship between this unique finding and NTM infection deserves further evaluation. It has been previously reported that key pathways related to the development of tissue fibrosis are differentially regulated based on sex,35 however, whether these differences are at play in NTM-PD is yet to be determined.

Females in our cohort were more prone to present with mid to lower lung disease, an increased incidence of GERD, and hiatal hernia compared to men, suggesting that GERD may be a greater contributor to NTM lung infection in women. These high rates of hiatal hernia on chest imaging, which have not previously been well described among demographically similar cohorts of individuals infected by NTM, suggest aero-digestive disease as a contributing factor to disease acquisition and progression. These findings highlight the importance of clinical assessment for the airway-esophageal interplay, and individuals with these findings may benefit from consultation with gastroenterologists and treatment of concomitant issues due in part to acid reflux.

Further, our study highlights the importance of chest imaging to determine underlying lung disease and inform adjunctive therapies in addition to the standard antimicrobial care.

Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that other factors, such as years of smoke exposure and packs-per-year, could influence outcomes, as well as diagnosis bias due to social constructs. While the majority of our patients were symptomatic, 54% of patients in the asymptomatic group presented with a history of smoking and none presented with M.abscessus infection. In this subset 47% were males, while in the nonsmoking asymptomatic group only 12% were males, suggesting different disease etiologies even in asymptomatic patients. Further studies addressing the interplay between host variability, predisposing factors, and hormonal signaling in NTM-PD will be required.

While this study shows significant sex-based differences in this NTM cohort, several limitations are also present. First, this study is a single-center study from the southeast region of the United States. Given the geographical variability of NTM species observed worldwide, it may not have global generalizability, and thus, other single-center and multicenter studies will be required to determine its applicability in other U.S. regions and worldwide. Likewise, this cohort was demographically homogenous with high rates of Whites in both male/female cohorts limiting the generalizability to international application where higher rates of smoking and post-tuberculosis lung disease, as well as alternative etiologies for the development of NTM lung infections, are more prominent. Lastly, images were performed for clinical purposes, and there was not a standardized method of imaging acquisition, including variability in slice thickness and with some patients having chest CT while others had high resolution CT with inspiratory and expiratory images. Thus, minor differences may have been noted if all images were obtained using the same modality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights key radiological, microbiological, and likely etiological differences between sexes in NTM infection. These observations may be applicable to other centers in the United States with equivalent demographics. Likewise, our observations may be relevant in cohorts where the etiology of NTM-PD in men is tied to a history of smoking, but not to post-tuberculosis NTM-PD. However, given the heterogeneity of the etiology of NTM-PD, future multicenter studies will be required to overcome the limitations of our single-center retrospective analysis. Similarly, larger studies will be necessary to address the applicability of our findings in areas where M. abscessus is more prevalent, as well as further assessment of sex-based adjunctive therapies.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: MM, LL, GH, and BG collected and compiled the clinical data. CM performed the analysis. CM and BG wrote the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript for final approval.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.