Running Head: Lipids, Target Genes, and COPD Risk

Funding Support: None

Date of Acceptance: October 31, 2025 | Published Online Date: November 10, 2025

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; CHD=coronary heart disease; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EAF=effect allele frequency; GERD=gastroesophageal reflux disease; GIANT=Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits; GLGC=Global Lipids Genetics Consortium; GSCAN=GWAS and Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine use; GWAS=genome-wide association study; HDL-C=high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IVs=instrumental variables; IVW=inverse-variance weighted; LD=linkage disequilibrium; LDL=low-density lipoprotein; LDL-C=low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MR=Mendelian randomization; MR-PRESSO=MR-pleiotropy residual sum and outlier; OR=odds ratio; RCTs=randomized controlled trials; SNP=single nucleotide polymorphism; STROBE-MR=Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-Mendelian Randomization; TG=triglyceride

Citation: Jia G, Guo T, Liu L, He C. Lipids, lipid-lowering drug target genes and COPD risk: a Mendelian randomization study. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(6): 512-521. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0632

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (2412KB)

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases, with a global prevalence rate second only to asthma. In some developing countries and economically underdeveloped regions, its prevalence is even higher than that of asthma.1,2 A 2019 study reported a global COPD prevalence of 10.3% among individuals aged 30–79 years, affecting approximately 400 million people.3 Despite the slightly lower global prevalence compared to asthma, COPD has a significantly higher mortality rate. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 identified chronic respiratory diseases as the third leading cause of death worldwide, with COPD responsible for over 80% of these deaths, accounting for approximately 3.3 million deaths annually.4

Statins are the most widely used lipid-lowering drugs and significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.5,6 Recent studies suggest that statins may also lower the risk of COPD. Several large observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have reported a reduced risk of COPD with statin use. For example, Schenk et al conducted a well-designed RCT showing that simvastatin reduced COPD exacerbations by 23% compared to placebo.7 A large meta-analysis of RCTs, including 1471 cases, further supported the protective effect of statins against COPD.8 However, the precise mechanism by which statins might benefit COPD remains unclear, and it is uncertain whether this is related to their lipid-lowering effects. Contrarily, a cross-sectional study of 107,301 adults in Denmark found that low serum levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were associated with an increased risk of COPD.9 Thus, the causal relationship between lipids and COPD remains controversial.

Observational studies have inherent limitations that make it difficult to establish causal associations between lipid levels and COPD. While RCTs are the gold standard for determining causality, they are constrained by study conditions.10 Mendelian randomization (MR) studies offer a promising alternative by using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to infer causal relationships between exposures and outcomes.11 Since genetic variants are randomly assigned at conception and are irreversible, MR studies can effectively control for confounding variables, avoid reverse causation, and provide robust causal inferences.12 For genetic variants to serve as valid IVs in MR analyses, they must satisfy 3 core assumptions: (1) Relevance—the genetic IVs are strongly associated with the exposure; (2) Independence—the genetic IVs are not associated with any potential confounders; and (3) Exclusion restriction—the genetic IVs influence the outcome solely through their effect on the exposure.13

In this study, we utilized 2-sample MR to investigate the causal relationships between serum lipid levels and COPD. We also performed drug target MR to assess the impact of lipid-lowering drug target genes on COPD. To ensure the robustness of our results, we conducted several MR sensitivity analyses, including the MR-pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) test, Cochran's Q test, MR-Egger intercept test, leave-one-out analysis, multivariable MR analysis, and colocalization analysis.

Methods

Study Design

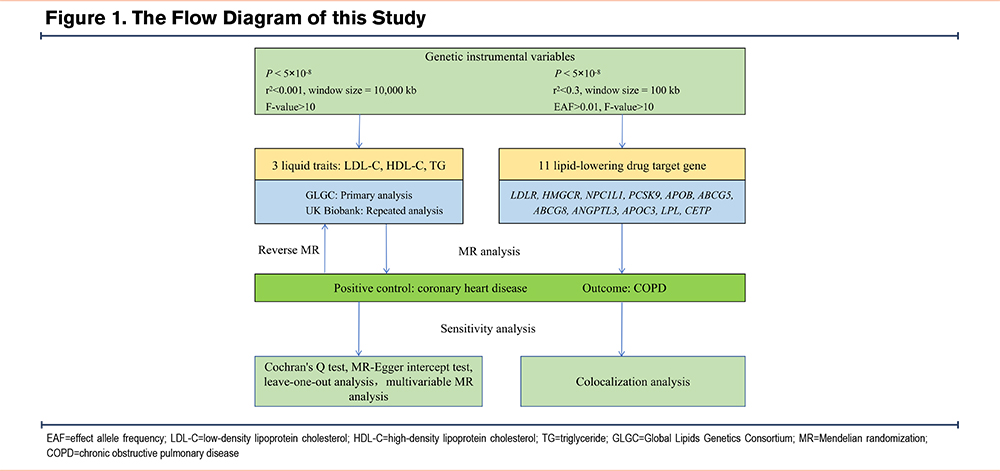

This study adheres to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-Mendelian Randomization (STROBE-MR) guidelines,14 see the STROBE-MR list for details. We used coronary heart disease (CHD) as a positive control to assess the effect of lipid levels on CHD. After confirming the reliability of the lipid genetic instruments, we proceeded with the formal MR analysis of lipids and COPD. First, we investigated the causal effects of 3 lipid traits—LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides—on COPD using 2-sample MR analyses. Additionally, to account for potential reverse causation, we also examined the causal effects of COPD on lipid levels. Given that smoking, obesity, asthma, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are established risk factors for COPD,1,15,16 we applied multivariable MR to adjust for these confounders and determine the direct causal effects of lipids on COPD. Lastly, to evaluate the impact of lipid-lowering drug target genes on COPD, we conducted drug target MR analyses. Multiple sensitivity analyses and colocalization analyses were performed to assess the robustness of our findings. The detailed study design is illustrated in Figure 1.

Data Sources

This study was a secondary analysis, utilizing data sourced from the extensive genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary database and large-scale GWAS meta-analyses that are publicly accessible. Ethical approval and informed consent of the participants were obtained in the original GWAS studies; therefore, no additional approval is required for this analysis.

Summary data on lipid traits were obtained from 2 independent GWAS databases: the Global Lipid Genetics Consortium (GLGC) and the UK Biobank. The GLGC is a global collaboration focused on the genetic basis of quantitative lipid traits. It identified 157 loci significantly associated with lipid levels in 188,578 individuals of European ancestry, providing the largest available GWAS summary data for lipid traits.17 We used GLGC data on LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides for the main analyses. The UK Biobank is a large GWAS database containing genetic data from 500,000 UK participants.18 GWAS data from the UK Biobank were used for replication analyses to validate causal effects.

Summary GWAS data for COPD were obtained from the FinnGen consortium, a large public-private partnership focused on genomics and personalized medicine. FinnGen has collected and analyzed genomic and health data from 500,000 Finnish biobank donors to understand the genetic basis of diseases.19 From the latest release 11, we obtained COPD GWAS summary data, which included 21,617 cases and 372,627 controls, with diagnoses based on International Classification of Diseases-8th, 9th, and 10th revision codes. To validate the IVs for lipid traits, we also obtained GWAS summary data for CHD from the Coronary Artery Disease Genome-wide Replication and Meta-analysis (CARDIoGRAM) plus the Coronary Artery Disease (C4D) Genetics (CARDIoGRAMplusC4D) consortium to use as a positive control.20

To determine the direct causal effect of lipid levels on COPD while correcting for potential confounders, we obtained GWAS summary data for smoking, body mass index (BMI), asthma, and GERD, all of which are established risk factors for COPD. The GWAS data for smoking, which included 3 phenotypes (smoking initiation, age of smoking initiation, and cigarettes per day), were sourced from the GWAS & Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine use (GSCAN). GSCAN conducted the largest meta-analysis of smoking-related GWAS to date, identifying 566 genetic variants associated with various stages of smoking among 1,232,091 participants.21 For BMI, GWAS summary data were obtained from the Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) consortium, which conducted the largest meta-analysis of BMI-related GWAS involving 681,275 individuals. The GIANT consortium is an international organization dedicated to the study of genetic loci for anthropometric traits, including height and BMI.22 The GWAS summary data for asthma were derived from the UK Biobank and included 53,598 cases and 409,335 controls. The GWAS summary data for GERD were taken from a meta-analysis by Jue-Sheng Ong et al, which included 129,080 cases and 473,524 controls.23 The full details of the GWAS summary data used in this study are presented in Table S1 in the online supplement.

Selection of Instrumental Variables

To ensure the reliability of the MR results, we established strict criteria for selecting IVs. Based on the foundational principles of MR and previous research, we developed the following criteria for genetic variants selection as IVs:

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) strongly associated with exposure were selected, meeting a genome-wide significance threshold of P<5×10-8 and a linkage disequilibrium (LD) threshold of r2<0.001, with a clump window of 10,000 kb;

- Weak IVs were excluded. SNP strength was assessed using the F-statistic, with SNPs considered weak if the F-value was less than 10. The F-statistic was calculated as F = R2/(1-R2 ) × (N-K-1)/K, where R2 = 2×MAF×(1-MAF)×β2. N is the sample size of the GWAS for exposure, K is the number of SNPs, and R2 represents the proportion of variance in exposure explained by the IVs24,25;

- SNPs associated with the outcome (P<5×10-8) were excluded;

- Palindromic SNPs and SNPs with incompatible alleles were removed when harmonizing genetic variants between exposure and outcome;

- Additionally, MR-PRESSO was used to identify and remove SNPs with high heterogeneity, ensuring more reliable MR results.26 The final SNPs selected were used as IVs for the MR analysis.

Based on the latest lipid management guidelines for lipid-lowering drugs and novel therapies, and informed by prior relevant studies,27,28 we identified 11 target genes encoding lipids using the DrugBank database.29 These included 7 target genes for lowering LDL-C: LDLR, HMGCR, NPC1L1, PCSK9, APOB, ABCG5, and ABCG8; 3 target genes for lowering triglycerides: ANGPTL3, APOC3, and LPL; and 1 target gene for elevating HDL-C: CETP. Detailed information on these target genes was retrieved from the National Library of Medicine. Detailed information is presented in Table S2 in the online supplement. Genetic variants were selected within 100kb upstream and downstream of the corresponding gene locations, following the variant selection methodology used in previous studies. Variants were required to have genome-wide significance (P<5×10-8) and no LD (R2<0.3, clump window=100kb). These variants were selected as IVs for lipid-lowering drug targets.

Statistical Methods

In all MR analyses in this study, the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method of random effect model is used as the main statistical method, supplemented by the MR-Egger regression and weighted median methods. The IVW method is a meta-summary of the effects of multiple SNP loci, which provides the most robust causal estimates in the absence of directed multiple effects.30 MR-Egger regression does not force the regression line to pass through the origin, allowing for the presence of directed gene multiple effects for the included IVs.31 The weighted median is the median of the distribution function obtained by ranking all individual SNP effect values according to their weights, simply by ensuring that 50% of the genetic variants are valid IVs.32 While MR-Egger regression and weighted median are not as statistically valid as IVW, they provide robust results in a wider range of situations. In the case of statistically significant results from the IVW method, the MR-Egger and weighted median results need only be directionally consistent with IVW for the MR results to be considered reliably statistically significant. Causal effects are expressed using odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The Bonferrroni method was used to correct for multiple testing of 3 lipid traits and 11 lipid-lowering drug target genes, with P<0.008 (0.05/6, bidirectional analyses) and P<0.004 (0.05/11), respectively, considered statistically significant.33

Sensitivity Analysis

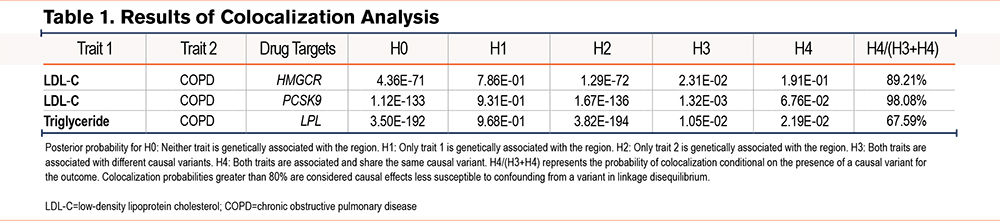

To ensure the robustness of the MR results, we conducted various sensitivity analyses, including Cochran's Q test, the MR-Egger intercept test, leave-one-out analysis, multivariable MR analysis, and colocalization analysis. Cochran's Q test was employed to assess heterogeneity. In MR analyses, heterogeneity is acceptable, and the IVW method of random effects model is less affected by heterogeneity.34 The MR-Egger intercept test was used to detect horizontal pleiotropy, which should be absent for a valid MR causal inference. Horizontal pleiotropy suggests the influence of confounding factors, rendering the MR results unreliable.31 Leave-one-out analysis was performed to determine whether the causal inference was driven by a single SNP. Multivariable MR analysis was applied to adjust for potential confounders and to evaluate the direct causal effects of lipids on COPD. This method extends univariable MR by incorporating genetic variation in multiple risk factors through multiple linear regression, thereby minimizing confounding influences.35 Colocalization analysis was used to validate the robustness of MR results for drug targets. Given the presence of a causal variant for the outcome, the analysis assesses potential confounding from LD by evaluating the posterior probability of different causal variants, shared causal variants, and colocalization. The primary output is the colocalization probability, which indicates the extent to which the same genetic variant affects both exposure and outcome traits. Colocalization probabilities greater than 80% are considered causal effects less susceptible to confounding from a variant in LD. We calculated the statistical power of the study using an online tool.36,37 The required parameters include sample size, the ratio of cases to controls, the coefficient of determination of exposure on genetic variants, causal effect, and significance level.

Statistical Software

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.4.1). Two-sample MR and sensitivity analyses were performed with the "TwoSampleMR" package (version 0.6.6), multivariable MR analyses with the "MendelianRandomization" package (version 0.7.0), and colocalization analyses with the "coloc" package (version 5.2.3).

Results

Causal Effects of Lipids on COPD

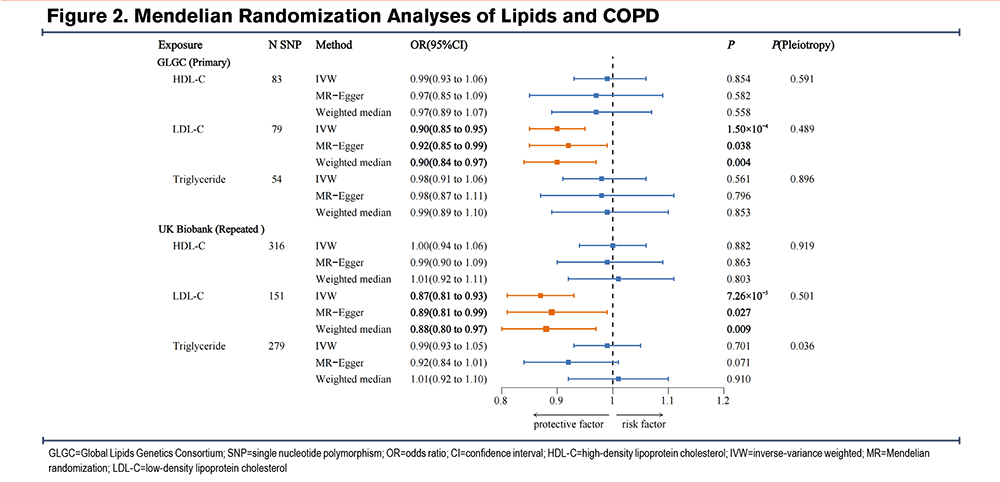

A total of 83 SNPs, 79 SNPs, and 54 SNPs were selected as IVs for HDL-C, LDL-C, and triglycerides, respectively, from the GLGC consortium. Weak genetic instruments are absent. Detailed information is provided in Tables S3-S5 in the online supplement. The genetic IVs for the 3 lipid traits were validated using CHD as a positive control. MR analyses identified significant associations: higher LDL-C and triglyceride levels were linked to an increased risk of CHD, while higher HDL-C levels were associated with a reduced risk. The validity of these IVs was confirmed (Table S6 in the online supplement).

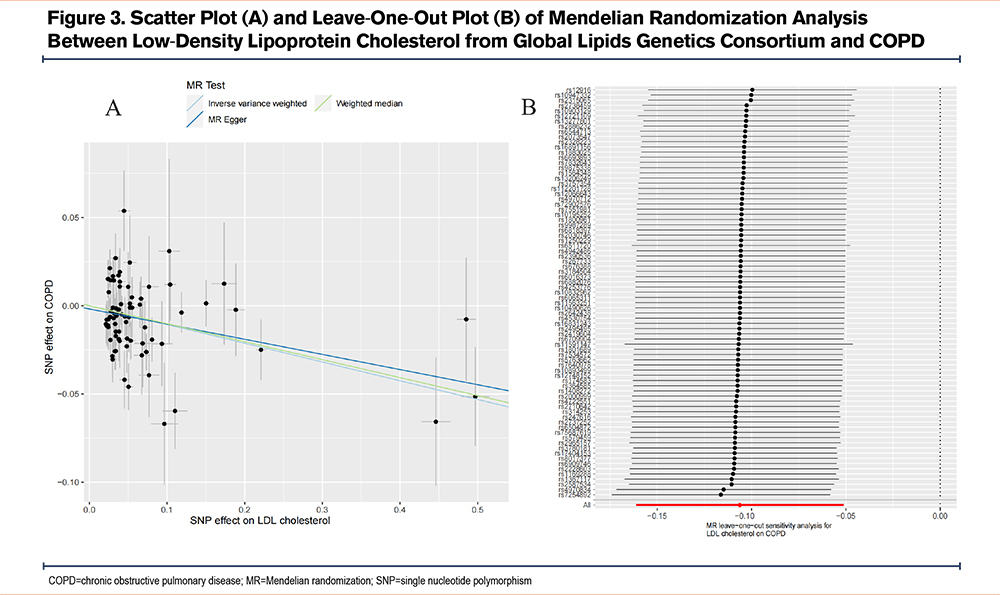

The IVW analysis indicated that genetically predicted serum LDL-C levels were associated with a reduced risk of COPD (OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.85–0.95, P=1.50×10-4). The weighted median analysis yielded similar results (OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.84–0.97, P=0.004), supporting the IVW findings. Although the MR-Egger analysis, after Bonferroni correction, was no longer statistically significant (OR=0.92, 95% CI=0.85–0.99, P=0.038), it remained directionally consistent with the IVW results. The MR-Egger intercept test did not detect pleiotropy (P=0.489). Cochran’s Q test indicated mild heterogeneity (P=0.002). Leave-one-out analysis showed no single SNP was driving the causal associations. The statistical power was 99.7%. No causal associations were found between HDL-C, triglycerides, and COPD risk (Figure 2 and Figure 3). These findings were validated in repeated analyses using GWAS data of the 3 lipid traits from the UK Biobank (Table S7 and Figure S1 in the online supplement).

To exclude the influence of potential confounders, we performed multivariable MR analysis to adjust for multiple risk factors and obtain the direct causal effect of LDL-C on COPD. The results demonstrated that the causal effect of LDL-C on COPD remained statistically significant after adjusting for confounders, including smoking initiation (IVW OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.85–0.95, P=1.50×10-4), cigarettes per day (IVW OR=0.89, 95% CI=0.84–0.94, P=8.53×10⁻⁵), age of smoking initiation (IVW OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.86–0.97, P=0.004), BMI (IVW OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.85–0.97, P=0.002), asthma (IVW OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.84–0.96, P=0.001), and GERD (IVW OR=0.92, 95% CI=0.87–0.98, P=0.012). The multivariable MR-Egger intercept test did not detect horizontal pleiotropy across all analyses (Figure S2 in the online supplement). To further rule out reverse causality, we assessed the effects of COPD on 3 serum lipid levels, and the MR analyses revealed no significant causal associations between COPD and 3 lipid traits (Table S8 in the online supplement).

Causal Effects of Lipid-Lowering Drug Target Genes on COPD

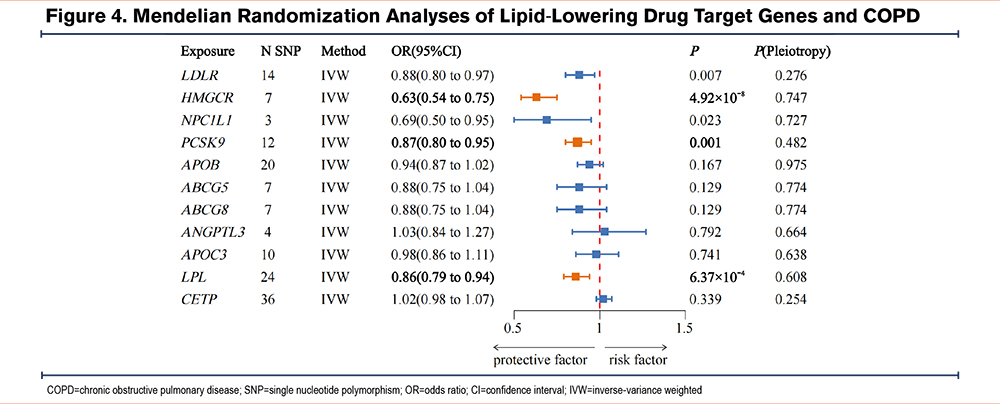

A total of 14 SNPs associated with LDLR, 7 SNPs with HMGCR, 3 SNPs with NPC1L1, 12 SNPs with PCSK9, 20 SNPs with APOB, 7 SNPs each with ABCG5 and ABCG8, 4 SNPs with ANGPTL3, 10 SNPs with APOC3, 24 SNPs with LPL, and 36 SNPs with CETP were identified as IVs related to lipid-lowering drug target genes. All IVs exhibit sufficient strength (Table S9 in the online supplement). MR analyses revealed causal relationships between 3 lipid-lowering drug target genes and a reduced risk of COPD: HMGCR (IVW OR=0.63, 95%CI=0.54–0.75, P=4.92×10-8), PCSK9 (IVW OR=0.87, 95%CI=0.80–0.95, P=0.001), and LPL (IVW OR=0.86, 95%CI=0.79–0.94, P=6.37×10-4) (Figure 4 and Figures S3-S5 in the online supplement). The statistical power was 100%, 77.5%, and 96%, respectively (Table S10 in the online supplement). No significant associations were identified between other lipid-lowering drug target genes and COPD (Table S11 in the online supplement).

Further colocalization analyses revealed that the colocalization probabilities for LDL-C and COPD in the HMGCR and PCSK9 genes were 89.21% and 98.08%, respectively. These findings suggest that the effects of HMGCR and PCSK9 on COPD are unlikely to be confounded by a variant in LD. In contrast, the colocalization probability for triglycerides and COPD in the LPL gene was 67.59%, indicating that confounding by LD cannot be excluded (Table 1).

Discussion

This study is the first to comprehensively investigate the causal associations between serum lipid levels, lipid-lowering drug target genes, and COPD risk. Using MR analysis, we genetically identified a robust causal association between higher LDL-C levels and a reduced risk of COPD, suggesting that LDL-C may serve as a protective factor. Additionally, causal relationships were identified between the HMGCR and PCSK9 genes and reduced COPD risk, indicating that inhibition of the 2 gene targets may increase COPD susceptibility. This finding appears to contradict the protective effect of statins on COPD, which may be explained by the pleiotropic effects of statins independent of their lipid-lowering action. Overall, our results suggest that the protective effects of statins on COPD are unlikely to be mediated by lipid reduction, and that lowering LDL-C levels could potentially increase COPD risk. However, these genetic findings require validation through further clinical studies.

Previous studies on the association between lipids and COPD have primarily focused on the effects of statins. Statins are the most commonly prescribed lipid-lowering drugs, reducing blood LDL-C levels by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, an enzyme encoded by the HMGCR gene that is essential for hepatic cholesterol synthesis.38 In addition to lowering cholesterol, statins possess anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects, which may provide therapeutic benefits in COPD. Studies have shown that statins exert anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway, suppressing the proliferation and aggregation of inflammatory cells, and reducing the expression of inflammatory mediators. Additionally, statins modulate the immune system by inhibiting the activation, adhesion, and migration of immune cells, such as monocytes, lymphocytes, and dendritic cells.39,40 Evidence supports the potential advantages of statins in COPD management. For instance, an Austrian RCT demonstrated that a daily dose of 40mg simvastatin significantly prolonged the time to first exacerbation and reduced the exacerbation rate in COPD patients.7 Similarly, a meta-analysis of large RCTs confirmed the protective effect of statins in COPD.8

The mechanism by which statins influence COPD, particularly whether this effect is attributable to lipid-lowering, remains unclear. Our study identified a causal association between elevated LDL-C levels and a reduced risk of COPD, suggesting that LDL-C may function as a protective factor. This implies that the protective effects of statins on COPD may not be linked to their lipid-lowering properties, and that lowering LDL-C levels might instead increase the risk of COPD. Supporting our findings, a Danish population study demonstrated that lower LDL-C levels are associated with a higher risk of COPD.9 Additionally, in examining the impact of lipid-lowering drug target genes on COPD, we found causal associations between 2 LDL-C-related genes—HMGCR and PCSK9—and a reduced risk of COPD. Similar observations were made by Holmes et al who reported that PCSK9 gene variants, while reducing LDL-C levels and cardiovascular risk, increased the risk of COPD.41 Based on these findings, we hypothesize that statins may exert dual effects on COPD. While their lipid-lowering properties could increase the risk of COPD, their anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions might offer protective benefits. Therefore, future research on statin therapy in COPD should consider baseline serum LDL-C levels. Statins with comparatively weaker lipid-lowering but stronger anti-inflammatory effects may yield more favorable outcomes. Further validation through well-designed studies is warranted.

The deposition of LDL-C in blood vessel walls contributes to atherosclerosis, a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In the cardiovascular field, LDL-C is often labeled as "bad cholesterol" and is generally considered to have no beneficial physiological function. However, this view is contested by some researchers. LDL-C plays a crucial role in transporting cholesterol, which is necessary for maintaining the structural integrity of cell membranes.42 Therefore, indiscriminate reduction of cholesterol may not be advisable. Studies indicate that individuals with mutations in the PCSK9 gene, or those using PCSK9 inhibitors, experience significant reductions in LDL-C levels and cardiovascular risk but exhibit increased susceptibility to certain lung diseases, including COPD and respiratory infections.41,43 This suggests a potential protective role of LDL-C in maintaining pulmonary health. Our research further confirms the protective effect of LDL-C in COPD. Although the exact mechanism remains unclear, previous studies suggest that it may be related to cholesterol's role in supporting immune function, as well as its anti-inflammatory and anti-infective properties. Immune dysregulation and inflammation are central to the pathogenesis of COPD, while infections are the primary cause of acute exacerbations and disease progression.44,45 LDL-C plays a key immunomodulatory role. Cholesterol is vital for the function of immune cells, and reduced cholesterol levels are associated with diminished activity in macrophages, T lymphocytes, and B lymphocytes.46-48 Furthermore, LDL-C exhibits anti-inflammatory and anti-infective effects. Animal studies have shown that LDL-C can reduce the expression of inflammatory genes in macrophages and neutralize bacterial toxins.49,50 These effects benefit lung health and may contribute to its protective role against COPD. However, the role of LDL-C in COPD requires further investigation and validation. Future research should include additional clinical and preclinical trials to more thoroughly elucidate the role of LDL-C in COPD.

The strengths of this study are notable. First, the use of 2-sample and multivariable MR avoided reverse causation, minimized confounding effects, and provided more robust conclusions. Second, we performed multiple sensitivity analyses and repeated our findings with another GWAS data on lipids, further strengthening the reliability of our results. Finally, we extended our investigation to the target gene level, exploring the relationship between lipid-lowering drug target genes and COPD risk.

However, this study has several limitations. Although we identified causal relationships between LDL-C levels, 2 coding genes, and a reduced risk of COPD, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In addition, the limited number of genetic instruments for certain lipid-lowering drug target genes and the presence of heterogeneity may compromise the robustness of our findings. While horizontal pleiotropy was minimized as much as possible, the complex biology of lipids and COPD may still introduce residual confounding. Furthermore, COPD is a highly heterogeneous disease, and the current GWAS database lacks sufficient subclassifications to support stratified analyses. Finally, our study was restricted to individuals of European ancestry, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations.

Conclusion

This study genetically identified causal relationships between serum LDL-C levels, the 2 coding genes HMGCR and PCSK9, and a reduced risk of COPD. These findings suggest that the protective effect of statins on COPD may occur independently of their lipid-lowering function. Further clinical validation is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: GJ was responsible for the study design. TG and LL oversaw the data curation. GJ, TG, and LL contributed to the formal analysis. GJ and CH were responsible for the methodology. TG and LL were in charge of the visualization. GJ wrote the original draft. CH supervised and was responsible for reviewing and editing.

Data sharing statement: The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

Other acknowledgements: We express our gratitude to the GWAS consortia, including FinnGen, GLGC, GSCAN, GIANT, CARDIoGRAMplusC4D, and UK Biobank, for their valuable contributions to the GWAS data. We also sincerely thank all the participants involved in the studies.

Declaration of Interests

The authors confirm they have no conflicts of interest.