Running Head: FeNO in Eosinophilic COPD

Funding Support: none.

Date of Acceptance: October 22, 2025 | Published Online Date: October 29, 2025

Abbreviations: APECS=Air Purification for Eosinophilic COPD Study; BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FeNO=fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; OR=odds ratio; SD=standard deviation

Citation: Morejon-Jaramillo PE, Ni W, Nassikas N, et al. Fractional exhaled nitric oxide in eosinophilic COPD. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(6): 522-526. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0701

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 While treatment has historically emphasized smoking cessation and inhaled therapies, accumulating evidence suggests that the eosinophilic COPD subtype may respond differently to corticosteroids and targeted biologics compared with noneosinophilic COPD.2,3

Improved characterization of eosinophilic COPD could enhance risk stratification and therapeutic targeting, but practical clinical biomarkers are limited. Blood eosinophils and interleukins are informative but not routinely obtained. Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) is a widely available, noninvasive marker of eosinophilic airway inflammation used to monitor asthma; however, whether it is a useful indicator of type 2 inflammation and risk of exacerbation in well-defined eosinophilic COPD that is targeted for biologics, steroids, and other therapies, is not well established.

We, therefore, examined whether FeNO levels are associated with peripheral eosinophil counts, asthma history, and severe exacerbation history among participants in the Air Purification for Eosinophilic COPD Study (APECS).4 We also evaluated whether clinically defined FeNO thresholds identify subgroups at increased risk of adverse outcomes.

Study Population

We analyzed baseline, prerandomization data from APECS, a randomized controlled trial conducted in the Northeastern United States. Participants were former smokers with spirometry-confirmed COPD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease5 [GOLD] stages 2–4), ≥10 pack-year smoking history, and an absolute eosinophil count ≥150cells/µL within the prior year. The trial protocol has been described previously.4

Data Collection

Demographics, medical history, and questionnaire data were obtained at enrollment and entered into REDCap.6 Participants reported physician-diagnosed asthma and COPD hospitalizations in the past 12 months. Education was categorized as more than some college versus less, and current inhaled corticosteroid use was abstracted from medication records and verified with participants.

Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide and Eosinophil Measurements

Peripheral blood eosinophils were measured at study entry. FeNO was assessed with the NIOX VERO® analyzer (NIOX; Oxford, United Kingdom) using standardized American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society protocols.7 Two reproducible measurements were averaged.

Statistical Analysis

Linear regression was used to examine associations of FeNO with blood eosinophil count, asthma diagnosis, and COPD hospitalization. Secondary analyses categorized FeNO as ≥25ppb (mildly elevated) and ≥50ppb (elevated) and assessed associations with asthma and hospitalization using logistic regression.8-10 Models adjusted for age, sex, education, body mass index, and inhaled corticosteroid use. Eosinophil counts were log-transformed for normality. Sensitivity analyses additionally adjusted for asthma history. Analyses were conducted using R 4.4.2, with p<0.05 considered significant.

Results

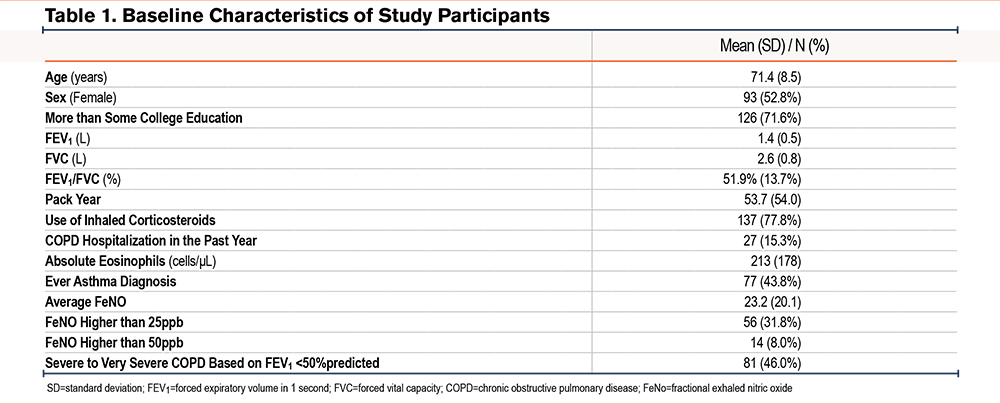

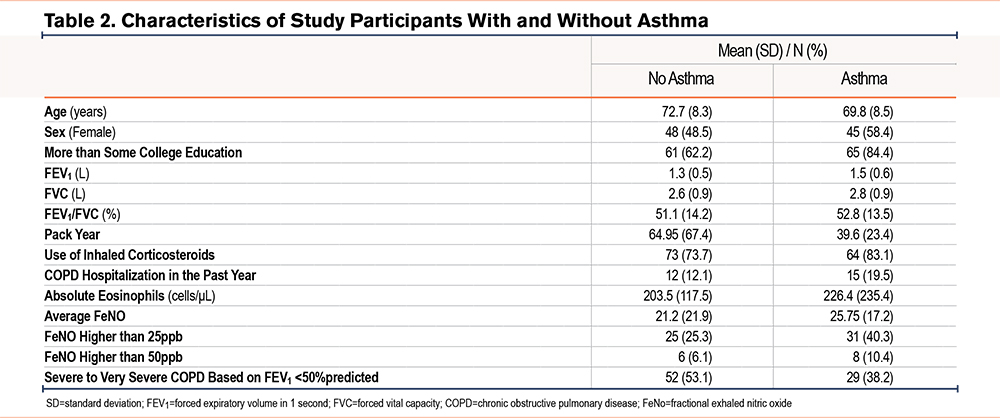

A total of 176 participants were included (mean age 71.4 years, 53% female). Nearly half (46%) had severe to very severe COPD. The mean FeNO was 23.2ppb (standard deviation [SD] 20.1); 32% had FeNO ≥25ppb and 8% had FeNO ≥50ppb. The mean eosinophil count was 213cells/µL (SD 178), and 44% reported a history of asthma. In the prior year, 15% had experienced a COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization (Table 1). Blood eosinophil counts were slightly higher in COPD patients with a previous diagnosis of asthma compared to those without (226 versus 203cells/μL), but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.41, Table 2). We also found blood eosinophil counts were slightly higher in COPD patients with a previous diagnosis of asthma compared to those without (238 versus 196cells/μL), but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.55).

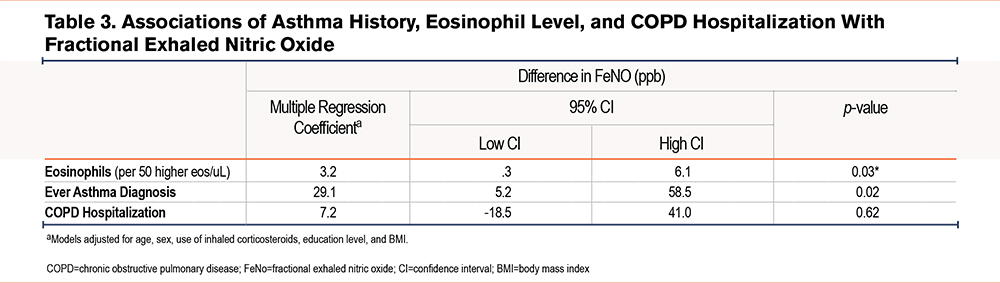

A higher blood eosinophil count was associated with higher FeNO (Table 3): each 50cells/µL increment corresponded to a 3.2% higher FeNO (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3%–6.1%). Asthma history was associated with 29.1% higher FeNO (95% CI: 5.2%–58.5%). No significant association was observed between a recent severe exacerbation and FeNO in continuous analyses.

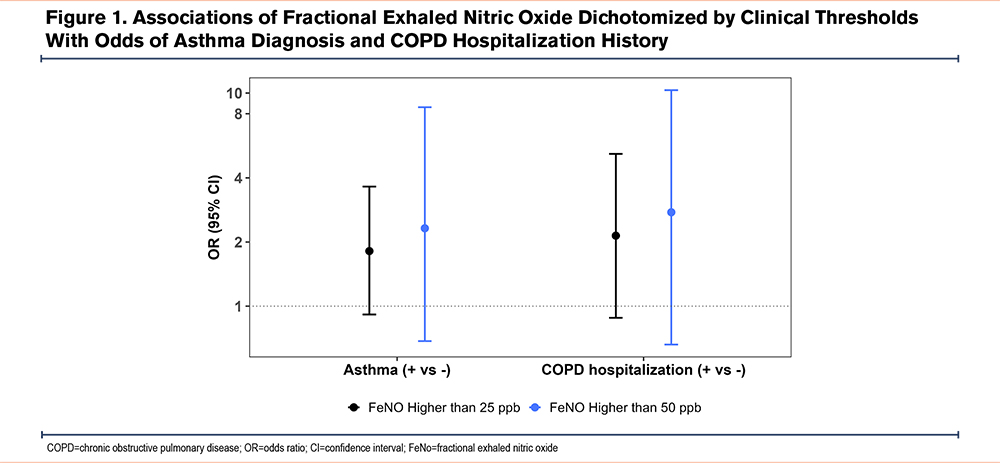

When FeNO was dichotomized, elevated FeNO (≥25ppb and ≥50ppb) was associated with greater odds of an asthma diagnosis and a severe exacerbation history, although CIs crossed the null (Figure 1). Sensitivity analyses adjusting for asthma produced similar results; for example, each 50cells/µL increase in eosinophil count was associated with a 2.9% higher FeNO (95% CI: 0.1%–5.8%).

Discussion

In this cohort of older former smokers with eosinophilic COPD, we found that higher FeNO was associated with higher blood eosinophils and a history of asthma. We also observed a pattern of greater odds of severe COPD exacerbation among participants with FeNO above clinical thresholds, although estimates did not reach statistical significance. Very few studies have measured FeNO in eosinophilic COPD. Our findings suggest that FeNO may serve as a practical biomarker of type 2 inflammation in COPD.

Our results align with prior studies showing correlations between FeNO and eosinophil counts in COPD8 and extend them by focusing specifically on a well-characterized eosinophilic COPD population. Importantly, associations between FeNO and eosinophils persisted after adjusting for asthma history, supporting an independent role of FeNO in this subtype. FeNO is attractive clinically because it is noninvasive, reproducible, and more widely available than sputum eosinophil or interleukin measurements.11,12

FeNO has also been linked to therapeutic response in COPD,11 including improved outcomes with inhaled corticosteroids among those with elevated levels. Our findings support the possibility that FeNO could be incorporated into treatment selection12 or monitoring strategies in eosinophilic COPD, similar to its established role in asthma.

This study has several limitations. Asthma history was self-reported, which may lead to misclassification. Our cross-sectional design precludes conclusions about causality, and exacerbation history was based on recall. In addition, we lacked direct measurement of airway or pulmonary eosinophils (such as sputum or tissue counts), and instead used blood eosinophil count as a practical proxy for airway type 2 inflammation; however, blood eosinophils only imperfectly correlate with sputum or tissue eosinophilia and can be influenced by concurrent illness or medications, which may affect associations with FeNO. Furthermore, current smokers were excluded from the study. While this exclusion reduces confounding related to active smoking status, it limits the generalizability of our findings to the broader COPD population, as some current smokers may display elevated FeNO levels. Nonetheless, the standardized measurement protocols, exclusion of active smokers, and detailed phenotyping strengthen the validity of our results.

Conclusion

FeNO was associated with higher blood eosinophil counts and asthma history in patients with eosinophilic COPD and showed a pattern of association with recent severe exacerbation. These findings suggest that FeNO may be a useful, noninvasive marker of type 2 inflammation and risk in this COPD subtype. Prospective studies are needed to determine whether FeNO can guide treatment selection and improve outcomes in eosinophilic COPD.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: PEMJ, ME, CD, and SS contributed to study execution and collected research data from participants. WN and PEMJ conducted the statistical analyses. PEMJ drafted the initial manuscript. WN, AS, NN, and MBR reviewed and edited the manuscript. MBR, AS, and NN conceptualized and framed the research questions of this research letter. MBR, WP, BC, and MR secured funding for the study and contributed to the overall study design. All authors contributed to the review of the scientific manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

Dr. Phipatanakul reports consulting fees and clinical trial support from Sanofi, Regeneron, Astra Zeneca, Genentech, and Novartis. Dr. Nassikas reports honoraria from Stanford University, Harvard University, Columbia University, and Desert Research Institute and payments from Industrial Economics Inc, unrelated to this work. Dr. Rice reports receiving honoraria from universities for research talks. The other authors have nothing to disclose.