Running Head: Tiotropium in COPD With Fixed Ratio Not Lower of Normal

Funding Support: The Tie-COPD study was supported in part by an investigator-initiated study program by Boehringer Ingelheim and by grants from the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the 12th and 13th National 5-Year Development Plan (2012BAI05B01 and 2016YFC1304101) and the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Research Department (2011B031800132).

This secondary analysis study was supported by the Foundation of Guangzhou National Laboratory (SRPG22-016 and SRPG22-018), the Clinical and Epidemiological Research Project of State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease (SKLRD-L-202402), the National Science Foundation of China (82570065), and the Plan on Enhancing Scientific Research in Guangzhou Medical University (GMUCR2024-01012).

Date of Acceptance: September 27, 2025 | Published Online: October 3, 2025

Abbreviations: CAT=COPD Assessment Test; CCQ=Clinical COPD Questionnaire; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second; FR=fixed ratio; FR+LLN+=fixed ratio criterion and the lower limit of normal criterion; FR+LLN-=patients with airflow limitation according to the fixed ratio but not the lower limit of normal; FVC=forced vital capacity; GLI=Global Lung Function Initiative; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; LLN=lower limit of normal; LSM=least-squares mean; mMRC=modified Medical Research Council; RR=relative risk

Citation: Zhou K, Wu F, Deng Z, et al. Tiotropium in patients with airflow limitation according to the fixed ratio but not the lower limit of normal: a secondary analysis of the Tie-COPD study. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(6): 466-476. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0629

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (868KB)

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous pulmonary condition with diverse lung lesions, complex clinical trajectories, and various disease presentations, making it a critical global health challenge.1 COPD ranks as the third leading cause of mortality worldwide, with its disease burden exacerbated by population aging and persistent environmental risk factors such as tobacco use and air pollution.2,3 The clinical complexity of COPD is further compounded by diagnostic uncertainties, particularly regarding its 2 essential spirometry criteria: the fixed ratio (FR) (the postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] to forced vital capacity [FVC] ratio of <0.70) and the lower limit of normal (LLN) criterion. Significant diagnostic discordance exists between these 2 criteria. Specifically, COPD exists in 3%–23% of patients in the general population with airflow limitation according to the FR criterion but not the LLN criterion (FR+LLN-) in clinical practices.4-7 FR+LLN- was previously dismissed and considered as “overdiagnosed COPD”; however, emerging evidence has challenged this viewpoint. The majority of studies have reported that patients with FR+LLN- had more serious chronic respiratory symptoms, more accelerated lung function decline, more frequent exacerbations, and more severe hospitalizations.5-7 Crucially, studies have shown that patients with FR+LLN- exhibited greater ventilatory inefficiency and an increased mortality risk compared with those with a normal FR.8,9 These findings underscore the clinical tendency for patients with FR+LLN- to have a poorer prognosis than those in whom both of the 2 criteria are normal. There is currently no evidence for the pharmacological treatment of patients with FR+LLN-, and there is no consensus on the therapeutic value in patients with FR+LLN-, which may restrict the disease management of this population in clinical practice.

Tiotropium is a potent drug used for the clinical management of COPD. As a long-acting anticholinergic bronchodilator, tiotropium selectively binds to muscarinic receptors on the smooth-muscle cells in the airways. Tiotropium treatment has been shown to inhibit goblet cell metaplasia induced by neutrophil elastase and mucin production in vitro in a rat model of COPD, indicating that tiotropium may help to treat mucus overproduction in COPD.10 In addition, maintenance tiotropium treatment has demonstrated significant advantages for improving lung function, delaying the rate of lung function decline, and reducing acute exacerbations, chronic pulmonary symptoms, and clinically important deterioration in mild-to-moderate COPD in various clinical studies.11-13

Our team previously conducted the Tiotropium in Early Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients in China (Tie-COPD) study, which did not use ≥LLN as an exclusion criterion. Owing to the lack of evidence on the effectiveness of tiotropium in patients with COPD with FR+LLN-, we conducted this secondary analysis of the Tie-COPD study using the baseline and follow-up data of patients with COPD with FR+LLN- treated with tiotropium to explore whether tiotropium improved respiratory health outcomes in this population.

Methods

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of the Tie-COPD study (NCT01455129), which was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial conducted to investigate the efficacy and safety of tiotropium in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD. The trial design and the results of the Tie-COPD study have been published previously.12,14 The Tie-COPD study recruited a large cohort of patients from 24 centers in China who were diagnosed with Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)1 stages 1 or 2 COPD (defined as a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC of <0.70 and an FEV1 ≥50% predicted) plus chronic respiratory symptoms, a history of exposure to COPD-risk factors, or both. The patients with GOLD stages 1 or 2 COPD were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either tiotropium (18μg once daily) or a placebo for 2 years. Follow-up of these patients was scheduled at 1 month and every 3 months thereafter. Patients with COPD exacerbations during the 4 weeks prior to screening, and those with asthma, large-airway disease, and/or severe systemic disease, were excluded from the Tie-COPD study.

The trial protocol was approved by the local institutional review board or independent ethics committee of each site.12,14 All patients provided written informed consent for participation. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Spirometry, Symptom, and Exacerbation Assessment

At each follow-up visit, data on smoking status, chronic respiratory symptoms, exacerbations, and medication administration were collected. Lung function data were collected at 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months during the follow-up period of this study. Spirometry assessment was performed by homogeneously trained technicians, following the normative operation methods and standard quality-control principles recommended by the American Thoracic Society and Europe Respiratory Society.15 There was at least a 6-hour interval between the administration of short-acting bronchodilators and spirometry testing. The postbronchodilator spirometry examination was required to have been performed 20 minutes after inhaling 400μg albuterol. According to the published protocol of the Tie-COPD study, the predicted FEV1 was obtained using the reference values from the European Coal and Steel Community 1993, adjusting for conversion factors for the Chinese population (0.95 for males and 0.93 for females).16,17 In the present secondary analysis, we recalculated the LLN of FEV1/FVC using the latest Chinese equations.18 The Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) race-neutral formula was not used to recalculate the LLN of FEV1/FVC because the GLI race-neutral formula has not been validated in the Chinese population.19-21 Patients with FR+LLN- were defined as having a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC of <0.70 but ≥ the LLN. Patients with airflow limitation according to both the FR criterion and the LLN criterion (FR+LLN+) were defined as having a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC of <0.70 and < the LLN. Respiratory symptoms were assessed using the modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale, COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score, and Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ).22 COPD exacerbation was defined as new onset or deterioration of at least 2 of the following 5 symptoms: cough, sputum production, purulent sputum, wheezing, and dyspnea persisting for at least 48 hours, excluding other causes, such as left and right heart insufficiency, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and arrhythmia.12,23 The severity of acute COPD exacerbations was assessed and recorded by well-trained staff according to the following categories: mild exacerbations were defined as a need for self-managed COPD-related medication and domestic treatment, moderate exacerbations were defined as those resulting in outpatient or emergency department visits and the need for COPD medication, and severe exacerbations were defined as those resulting in hospitalization.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the difference between the tiotropium and the placebo groups in the change from baseline to 24 months in the prebronchodilator FEV1.

The secondary endpoints were the between-group difference in the change from baseline to 24 months in postbronchodilator FEV1, the between-group difference in the change in prebronchodilator and postbronchodilator FVC from baseline to 24 months, the between-group difference in the annual decline in the prebronchodilator and postbronchodilator FEV1 from 30 days to 24 months, the between-group difference in the annual decline in the prebronchodilator and postbronchodilator FVC from 30 days to 24 months, the annual frequency of acute exacerbations, the CAT score, and the CCQ score.

Statistical Methods

This study was a secondary analysis, therefore, no sample size calculation was performed. We included all eligible patients with FR+LLN- from the full analysis set of the Tie-COPD study in this secondary analysis. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as n (%). We evaluated the differences between the clinical characteristics at baseline between the 2 groups using the 2-sample t-test, Chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. We used repeated-measures analysis of variance to clarify the between-group difference in the change from baseline to 24 months in the prebronchodilator FEV1, the postbronchodilator FEV1, the prebronchodilator FVC, and the postbronchodilator FVC. The random coefficient regression model was used to assess the between-group difference in the annual rate of lung function decline rate from 30 days to 24 months based on the prebronchodilator FEV1 and other spirometry indicators. The measurement values collected at each screening visit were regarded as the dependent variables in the analyses, combined with group, visit (used as a continuous variable), and interactions between groups and visits as fixed effects, and patients as random effects. The Poisson regression model was used to compare the frequency and severity of acute COPD exacerbations, considering the exposure to the trial regimen doses and adjusting for overdispersion (i.e., the presence of greater variability in the data set than the expected heterogeneity in the exacerbation rates). We also used repeated-measures analysis of variance model analyses to clarify the between-group difference in the change from baseline to 24 months in the CAT scores and the CCQ scores. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

Results

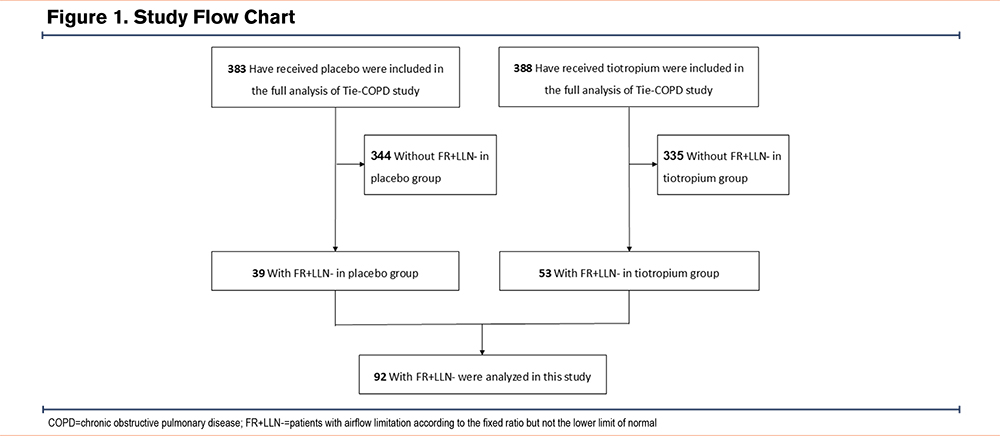

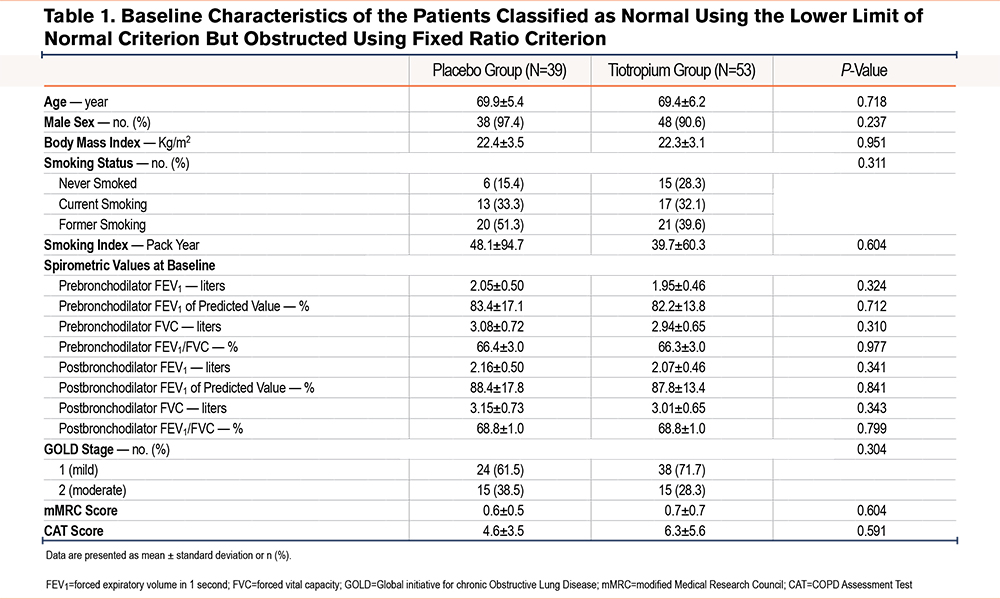

Of the 841 randomized patients, 771 were included in the full analysis set in the Tie-COPD study (Figure 1). Of these, 92 patients (12%) had FR+LLN- (53 in the tiotropium group, 39 in the placebo group). There were no significant differences in the baseline clinical characteristics between the tiotropium group and the placebo group (Table 1), including age (69.4 ± 6.2 years versus 69.9 ± 5.4 years, respectively), sex, postbronchodilator percentage predicted FEV1 (87.8% ± 13.4% versus 88.4% ± 17.8%), and FEV1/FVC (68.8% ± 1.0% versus 68.8% ± 1.0%).

Primary Endpoint

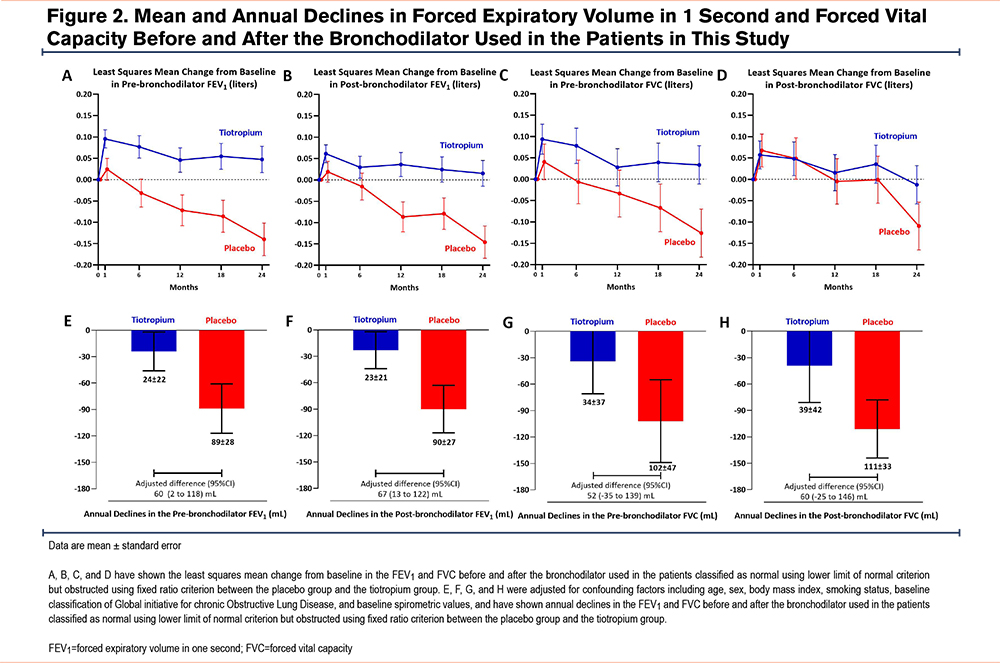

The least-squares mean (LSM) change from baseline to 24 months in the prebronchodilator FEV1 was 47mL (95% confidence interval [CI] -13, 108) in the tiotropium group and -140mL (95% CI -215, -64) in the placebo group (Figure 2). Tiotropium led to a significantly higher prebronchodilator FEV1 at 24 months compared with placebo (LSM difference 191mL; 95% CI 99, 283). The improvement was generated from month 6 and was sustained through month 24.

Secondary Endpoints

The results of the between-group difference in the change from baseline to 24 months in postbronchodilator FEV1, and pre- and postbronchodilator FVC are shown in Figure 2. Tiotropium led to a significantly greater postbronchodilator FEV1 at 24 months (LSM difference 139mL; 95% CI 38, 223) than placebo. The LSM change from baseline to 24 months in postbronchodilator FEV1 was 1mL (95% CI -44, 75) in the tiotropium group and -130mL (95% CI -220, -71) in the placebo group. This improvement was generated from month 6 and was sustained through month 24. Tiotropium also resulted in a significantly higher prebronchodilator FVC at 24 months than placebo. The between-group LSM difference from baseline to 24 months was 175mL (95% CI, 44 to 306). The LSM change from baseline to 24 months was 33mL (95% CI -55, 122) in the tiotropium group and -126mL (95% CI -237, -16) in the placebo group. Tiotropium led to a significantly higher postbronchodilator FVC at 24 months than placebo. The between-group LSM difference in postbronchodilator FVC was 100mL (95% CI -33, 233). The LSM change from baseline to 24 months was -13mL (95% CI -101, 75) in the tiotropium group and -109mL (95% CI -219, 1) in the placebo group.

Figure 2 shows that the tiotropium group exhibited lower lung function decline from baseline to 24 months than the placebo group, as shown by the pre- and postbronchodilator FEV1 and/or FVC values. The annual decline in prebronchodilator FEV1 in the tiotropium group was lower than in the placebo group (24mL/year versus 89mL/year, respectively; adjusted difference 60mL/year; 95% CI 2, 118) from 30 days through 24 months. Similar results were observed for the postbronchodilator FEV1. The between-group adjusted difference from 30 days through 24 months in the annual decline in postbronchodilator FEV1 was 67mL/year (95% CI 13, 122), with an annual decline of 23mL/year in the tiotropium group compared with 90mL/year in the placebo group. Tiotropium reduced the annual decline in prebronchodilator FVC compared with placebo (34mL/year versus 102mL/year, respectively; adjusted difference 52mL/year; 95% CI -35, 139); however, this result was not statistically significant. Similarly, tiotropium insignificantly reduced the annual decline in postbronchodilator FVC compared with placebo (39mL/year versus 111mL/year; adjusted difference 60mL/year; 95% CI -25, 146) from 30 days through 24 months.

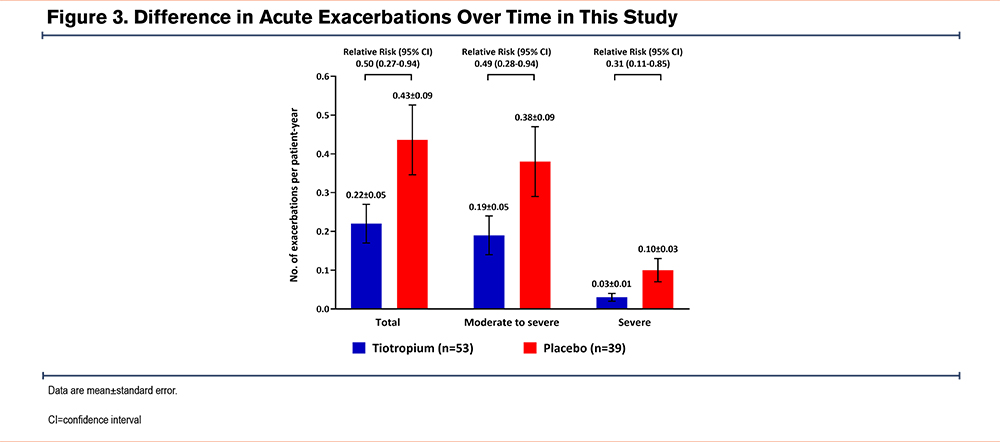

The annual frequency of acute COPD exacerbations was lower in the tiotropium group than in the placebo group (0.22 ± 0.05 per patient year versus 0.43 ± 0.09 per patient year, respectively; relative risk [RR]=0.50; 95% CI, 0.27–0.94). Similar results were observed for moderate-to-severe COPD exacerbations (0.19 ± 0.05 per patient year versus 0.38 ± 0.09 per patient year; RR=0.49; 95% CI, 0.28–0.94) and severe COPD exacerbations requiring hospitalization (0.03 ± 0.01 per patient year versus 0.10 ± 0.03 per patient year; RR=0.31; 95% CI, 0.11–0.85) (Figure 3).

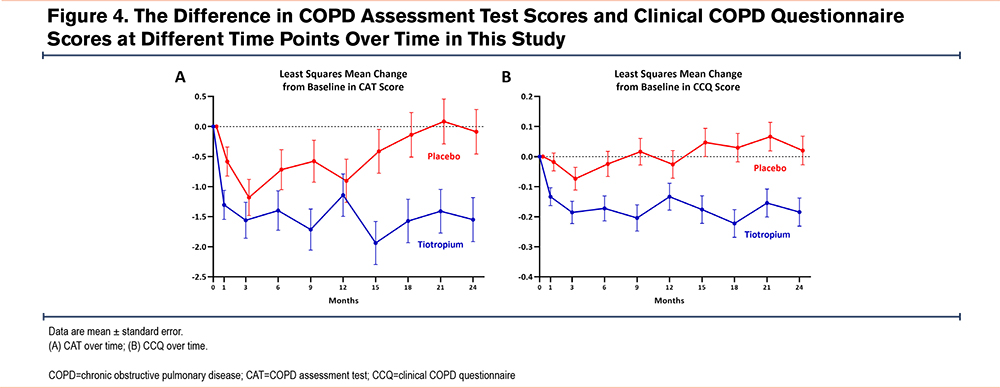

As for chronic respiratory symptoms, the tiotropium group demonstrated significantly reduced CAT scores from baseline to 24 months (LSM change -1.55; 95% CI -2.26, -0.83) compared with the placebo group (LSM change -0.09; 95% CI -0.82, 0.64). The between-group difference was -1.92 (95% CI -2.85, -1.00) (Figure 4). The LSM change in the CCQ score from baseline to 24 months in the tiotropium group was -0.22 (95% CI -0.34, -0.10) compared with 0.02 (95% CI -0.07, 0.11) in the placebo group. The between-group difference was -0.18 (95% CI -0.28, -0.09).

In patients with FR+LLN+, the LSM change from baseline to 24 months in prebronchodilator FEV1 was 30mL (95% CI -1, 60) in the tiotropium group and -129 mL (95% CI -159, -99) in the placebo group (Supplementary Figure 1 in the online supplement). Tiotropium led to a significantly greater prebronchodilator FEV1 at 24 months (LSM difference 141mL; 95% CI 98, 184) than placebo. Similar findings were observed in the postbronchodilator FEV1, prebronchodilator FVC, and postbronchodilator FVC. From 30 days through 24 months, the annual decline in the postbronchodilator FEV1 was 28mL per year in the tiotropium group and 44mL per year in the placebo group, with a between-group adjusted difference of 17mL/year (95% CI 1, 34). The groups did not differ significantly in the annual decline of the prebronchodilator FEV1, prebronchodilator FVC, and postbronchodilator FVC. Tiotropium also resulted in a lower frequency of total exacerbations (0.50 ± 0.60 per patient year versus 0.88 ± 0.09 per patient year, respectively; RR=0.56; 95% CI, 0.46–0.67) compared to placebo (Supplementary Figure 2 in the online supplement). In terms of chronic respiratory symptoms, the tiotropium group showed visibly reduced CAT scores from baseline to 24 months (LSM change -1.70; 95% CI -2.36, -1.05) compared with the placebo group (LSM change -0.24; 95% CI -0.90, 0.41). The between-group difference was -1.21 (95% CI -2.85, -1.00) (Supplementary Figure 3 in the online supplement). The above results remain stable in CCQ scores.

Discussion

The secondary analysis revealed that tiotropium improved lung function, and reduced lung function decline, exacerbations, and chronic respiratory symptoms compared with placebo in patients diagnosed with airflow limitation according to the commonly used FR of 0.70 but not the LLN.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment for patients with FR+LLN-. Patients with FR+LLN- are prone to a better health status than those with FR+LLN+ and exhibit better lung function, fewer respiratory symptoms, and better respiratory outcomes, and thus, this group of patients is often considered to be overdiagnosed COPD. However, patients with FR+LLN- are associated with increased respiratory symptoms, poorer lung function, a higher risk of exacerbations, and a higher risk of mortality than patients in whom both criteria are normal.5-9 The present study provided evidence-based medicine support for the pharmacological treatment of this special population.

Three novel findings of this study may contribute to guiding the treatment of patients with FR+LLN- in clinical practice. First, we demonstrated that tiotropium visibly improved FEV1 at month 24 by approximately 139mL to 191mL more than placebo in patients with FR+LLN-. The 24-month duration of the Tie-COPD study captured longitudinal lung function trajectories more reliably. Second, tiotropium effectively reduced the annual rate of lung function decline in patients with FR+LLN- compared to the placebo during the 24 months. Tiotropium alleviated the annual decline in postbronchodilator FEV1 (23mL/year versus 90mL/year in the placebo group) over 24 months. The 23mL/year annual decline in prebronchodilator FEV1, an effect size comparable to that observed with tiotropium in patients with GOLD stages 2 or 3 COPD (34mL/year in the Understanding Potential Long-term Impacts on Function with Tiotropium study), suggests its biological plausibility despite diagnostic reclassification.24 Third, tiotropium reduced exacerbations and alleviated chronic pulmonary symptoms in patients with FR+LLN- compared with the placebo. Overall, the effectiveness of tiotropium for improving respiratory health outcomes among patients with FR+LLN- was multidimensional.

The proportion of patients with FR+LLN- in the Tie-COPD study was 12%, which is consistent with previous studies, and whether these special populations require treatment is an interesting question.4-7 In this study, the rate of annual decline in prebronchodilator FEV1 was 89mL in the placebo group, which is much higher than the natural age-related decline of approximately 30mL/year in healthy, aging individuals.25,26 The annual decline in prebronchodilator FEV1 was 89mL in the placebo group in this analysis, which is higher than the value of 53mL in the placebo group of the entire Tie-COPD study. A similar trend was observed for postbronchodilator FEV1.12 These findings indicate that patients with FR+LLN- have faster lung function decline than the overall population with mild-to-moderate COPD. Moreover, the disease burden of patients with FR+LLN- is heavier than that of those with a normal fixed ratio.4-7 The above information has challenged the conventional viewpoint that these milder cases may not require pharmacological intervention, indicating that patients with FR+LLN- may require integrated management, early intervention, and long-term follow-up to improve their respiratory outcomes.

Tiotropium is a long-acting anticholinergic bronchodilator that selectively binds to muscarinic receptors on smooth-muscle cells in the airway. Previous studies have shown that tiotropium ameliorates airway limitation, reduces air trapping and exertional dyspnea, and improves exercise tolerance and health-related quality of life among patients with COPD.27 The results of the present study reveal that tiotropium effectively improved lung function, delayed lung function decline, and reduced the risk of acute exacerbation among patients with FR+LLN-, supporting the pharmacological intervention and management of these patients in clinical practice. Large population-based cohort studies and clinical trials are still needed to verify the efficacy of pharmacological treatment in patients with FR+LLN- and to explore appropriate therapeutic medication.

The impact of the 2 criteria of interest (FR and LLN) on the diagnosis of COPD has always been a key issue in respiratory medicine. The use of the FR for the diagnosis of COPD was first recommended in the GOLD 2001 guidelines, originating from large-sample prevalence results.28 The FR has been used ever since, owing to its simplicity and suitability for use in clinical practice and its standardization.1 However, one of the problems that arose with the use of the FR was the underdiagnosis of younger patients and the overdiagnosis of older patients.29 The LLN criterion is based on the 5th percentile of the normal distribution of the healthy population and is adjusted for age, sex, height, and race, which had greater potential for accurately reflecting patients’ lung function.11,30 However, the latest strategy proposed the implementation of a more inclusive diagnosis of COPD, allowing for the detection of early disease before irreversible pathological changes have occurred, enabling early disease interception.31 The incidence of COPD detected by the LLN criterion is lower than that detected by the FR criterion (6.1% versus 7.6%) among patients aged 40–49 years, which may not conform to the latest prevention and treatment strategy for COPD.32,33 Moreover, previous studies have evidenced that the FR criterion is no less effective for detecting COPD-relevant hospitalization and mortality than the LLN criterion or other fixed thresholds used to define airflow limitation.34 Last, patients with FR+LLN- are visibly older, have milder symptoms, and have a higher risk of cardiovascular disorders and/or mortality than those with FR−LLN-, indicating that satisfying the LLN criterion may not suggest that the respiratory system is healthy, even though they have a lower risk of exacerbations than FR−LLN-.4,35-37 Our findings support the use of the FR criterion to identify patients who are at a high risk of clinically significant COPD. Therefore, this criterion may be suitable for use in routine clinical practice and COPD treatment, especially in low- and/or middle-income countries that have not conducted large-scale studies to calculate their own LLN formulas.

This study has some potential limitations. This was a post hoc analysis and no preplanned sample size calculation was performed. This may have led to false-positive results and insufficient power to classify the differences between the tiotropium and placebo groups. Moreover, a potential imbalance in the clinical characteristics between the 2 groups may have influenced the study results. Furthermore, the sample size was small, and thus, we could not conduct clinically relevant subgroup analyses.

Conclusion

The results of this secondary analysis of the Tie-COPD study demonstrated that tiotropium improved lung function, ameliorated lung function decline, reduced acute exacerbations, and reduced chronic pulmonary symptoms compared with placebo in patients with FR+LLN-, providing evidence for the pharmacological treatment of this population.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: KZ, FW, PR, and YZ were responsible for the conception and design of the manuscript. PR, NZ, and YZ gave administrative support. PR and YZ were in charge of the provision of study materials or patients. All authors were responsible for the collection and assembly of data. FW, KZ, ZD, QW, NZ, PR, and YZ were in charge of the data analysis and interpretation. KZ, FW, ZD, QW, NZ, PR, and YZ were responsible for the manuscript writing. All authors gave their final approval of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement: The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Other acknowledgements: We thank Ming Tong, Ben Zhang, and Naiqing Zhao (clinical research managers of Rundo International Pharmaceutical Research and Development) for contributions in monitoring and statistical support.

Tie-COPD Study Investigators:

National Center for Respiratory Medicine, State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Health, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University: Yumin Zhou, Xiaochen Li, Shuyun Chen, Jinping Zheng, Dongxing Zhao, Weijie Guan, Nanshan Zhong, Pixin Ran

The Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University: Weimin Yao, Biao Liang

Guangzhou Panyu Center Hospital: Rongchang Zhi, Yinhuan Li

The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University: Liping Wei, Guoping Hu

Chenzhou No 1 People’s Hospital: Bingwen He, Hui Tan

Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital: Xiangyan Zhang, Xianwei Ye

Wengyuan County People’s Hospital: Changli Yang, Lizhen Zeng, Changxiu Ye

Henan Provincial People’s Hospital: Ying Li, Xitao Ma

Liwan Hospital Guangzhou Medical University: Fenglei Li, Yan Chen

The Affiliated Hospital of Guiyang Medical College: Juan Du, Xiwei Hu

The Second People’s Hospital of Hunan Province: Jianping Gui, Jia Tian

Huizhou First Hospital: Bin Hu, Zhe Shi

The Affiliated Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University: Chunxue Bai, Xiaodan Zhu

Shenzhen Sixth People’s Hospital: Ping Huang, Xiufang Du

The First People’s Hospital of Foshan: Gang Chen, Minjing Li

Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology: Yongjian Xu, Jianping Zhao

Xinqiao Hospital: Changzheng Wang, Qianli Ma

The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University: Shengming Liu;

Shanghai Xuhui Central Hospital: Ronghuan Yu

The First Affiliated Hospital Sun Yat-sen University: Canmao Xie;

The Second People’s Hospital of Zhanjiang: Xiongbin Li

Shaoguan Iron and Steel Group Company Limited Hospital: Tao Chen

Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital: Yingxiang Lin

Lianping County People’s Hospital: Weishu Ye, Xiangwen Luo, Lingshan Zeng, Shuqing Yu

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.