Running Head: Body Mass Index and Bronchodilator Responsiveness

Funding Support: The Pulmonary Risk in South America (PRISA) and CRONICAS studies were funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) (contracts HHSN268200900029C and HHSN268200900033C). ANS, AGL, and WC are also funded by Fogarty International Center of the NIH (D43TW011502).

Date of Acceptance: September 2, 2025 | Published Online: October 3, 2025

Abbreviations: ATS=American Thoracic Society; BDR=bronchodilator responsiveness; BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; IL=interleukin; OR=odds ratio; PLATINO=Latin American Project for Research in Pulmonary Obstruction; PRISA=Pulmonary Risk in South America study; SD=standard deviation; WHO=World Health Organization

Citation: Soriano-Moreno AN, Lescano AG, Gilman RH, et al. Body mass index and bronchodilator responsiveness in adults: analysis of 2 population-based studies in 4 South American countries. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(6): 477-489. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.608

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (320KB)

Introduction

The prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases is increasing worldwide, and South America is no exception. A recent systematic review1 estimated that the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in South America was 3.4% over a 9-year follow-up period among individuals aged ≥ 35 years, while its prevalence was estimated at 8.9%. Uruguay (10.2%) and Argentina (11.7%) suffer the highest burden of COPD in the continent.1 High prevalence rates of asthma have also been reported. For example, in 2002, the overall prevalence of current wheezing was 15.9% in Latin America, higher than the global average of 14.1%. Lima, Peru, has one of the highest asthma prevalence rates in the world, with 19.6% for current wheezing and 33.1% for lifetime asthma.2 Chile (15.4%), Argentina (11.2%), and Uruguay (11.2%) also reported having a high prevalence of current wheezing when compared to other countries around the world.3

Bronchodilator responsiveness (BDR) is commonly evaluated in individuals with chronic respiratory diseases.4 Indeed, BDR may help to identify patients who benefit from inhaler therapy,5 and it is widely used in both asthma and COPD research studies.6 The presence of BDR has been associated with more respiratory symptoms, frequent exacerbations, and lower quality of life among individuals with asthma and COPD.7 Additionally, its presence is linked to a higher likelihood of experiencing wheezing, shortness of breath, and fatigue, even in individuals without a history of respiratory disease.8 In earlier studies,7,9,10 BDR prevalence was found to be between 3.1% and 7.0%. Investigators of the Latin American Project for Research in Pulmonary Obstruction (PLATINO) study, conducted in Brazil, Mexico, Uruguay, Chile, and Venezuela, found a mean BDR prevalence of 7.0% in adults aged ≥ 40 years.10

The epidemiology of BDR, however, is not well understood. Factors such as anthropometric characteristics may also influence its variability. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how obesity-related physiological changes could potentially affect BDR. Obesity-related hyperinsulinemia has been shown to aggravate airway bronchoconstriction through increased vagal stimulation. This effect is mediated by a reduction in the inhibitory function of presynaptic M2 muscarinic receptors, which leads to excessive acetylcholine release and enhanced cholinergic tone in the airways, even without altering smooth muscle contractility.11 Obesity reduces tidal volume and functional residual capacity, which limits the stretch of airway smooth muscle during breathing. This lack of mechanical strain favors a sustained contractile state known as the latch mechanism, in which muscle relaxation is delayed and tone remains elevated. This phenomenon contributes to impaired airway function, even in the absence of structural obstruction.12 Third, leptin has been shown13 to induce a proinflammatory cascade in the airways due to activating the spliced form of X-box binding protein 1, which triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress and promotes the production of Th2 cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13. These cytokines are involved in eosinophilic airway inflammation and have been associated with increased bronchodilator responsiveness by clinical studies that have evidence that individuals with eosinophilic asthma tend to have poorer baseline lung function but exhibit a larger improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) after salbutamol administration, reflecting highly reversible airflow obstruction.14

Studies examining the relationship between body mass index (BMI) and BDR have reported inconsistent results. Some studies have found BMI to be a risk factor for BDR,7,15,16 while others have not.8,9,17-19 One population-based study found that individuals with a higher BMI had a greater bronchodilator-induced change in FEV1, even after excluding those with obstructive disease.16 In contrast, other studies have not demonstrated an independent effect of BMI after adjusting for baseline lung function or respiratory comorbidities. For example, a multicenter study in adults aged ≥40 years found that a higher BMI was associated with having BDR in single variable analysis, but not in multivariable analysis.8 These findings suggest that while some evidence supports an association between adiposity and increased spirometric reversibility, it remains unclear whether BMI has a consistent and independent effect on BDR.

Understanding the association between BMI and BDR has become increasingly important, as excess weight has reached epidemic proportions in South America, where 1 in 3 adults is overweight or obese.20 Despite the high prevalence of obesity and the clinical importance of BDR, few studies have explored this relationship using standardized spirometry in large population-based samples across different settings. We aimed to assess the association between BMI and BDR using prospectively collected data in adults from 4 South American countries. We hypothesized that higher BMI would be associated with increased BDR, based on prior evidence and through its inflammatory effects on airway physiology. We also explored whether this association differed according to the presence or absence of chronic respiratory diseases.

Methods

Study Design

We analyzed cross-sectional data from 2 population cohort studies conducted in South America. The CRONICAS cohort study21 was conducted in 4 settings in Peru, while the Pulmonary Risk in South America (PRISA) study22 was conducted in 2 cities in Argentina, 1 in Chile, and 1 in Uruguay. Both studies were designed as prospective observational studies to assess chronic conditions in the general population, with a minimum follow-up of 4 years. The CRONICAS cohort study was approved by the ethics committees of Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University. The PRISA study was evaluated and approved by ethics committees in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and the United States. In both studies, all participants provided informed consent before data collection. This secondary analysis was reviewed and approved by the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia ethics committee before its implementation.

Study Population

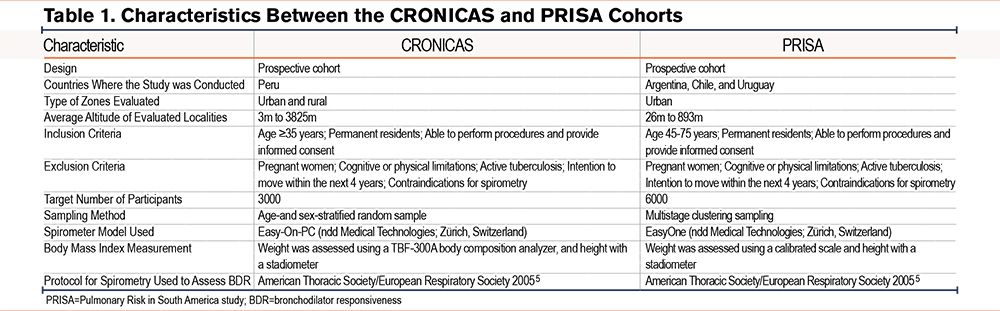

We summarized the study designs of the CRONICAS and PRISA cohorts in Table 1. Both studies included permanent residents who could provide informed consent and complete the data collection procedures. Participants were excluded if they intended to move within the next 4 years, were unable to respond to the questionnaire or provide informed consent, had active tuberculosis, were pregnant, or had contraindications for spirometry.

We used spirometry and anthropometry data collected during the enrollment visit of both studies. CRONICAS aimed to enroll 1000 participants each from Lima and Tumbes, both found at sea level, and 500 each from the urban and rural areas of Puno, at 3825 meters above sea level. Participants were selected through stratified random sampling by sex and age. PRISA enrolled a total of 1500 participants per city, using a 3-stage stratified cluster sampling method. In the first stage, 60 clusters were randomly selected from the latest national census data, stratified by socioeconomic status. In the second stage, 40 households per cluster were selected using systematic sampling. In the third stage, 1 randomly selected household member was enrolled, ensuring an equal distribution of men and women.

Only 1 randomly selected participant per household was enrolled in both cohorts. After obtaining informed consent, field workers conducted face-to-face interviews using standardized questionnaires to collect sociodemographic information, clinical history, respiratory conditions, and smoking habits. They also performed clinical evaluations, including spirometry and anthropometric assessments.

Spirometry

Data collection teams in both studies received spirometry training and were subsequently evaluated to ensure proficiency in the procedure and the performance of high-quality tests. In both studies, field staff visited the homes of participants selected through sampling as described above. Those who met the eligibility criteria were invited to participate in the study, and those who agreed provided informed consent. Spirometry was performed according to the 2005 American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society guidelines.23 FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC were measured before and after administering 200µg of inhaled salbutamol. This procedure was conducted using Easy-On-PC spirometers in the CRONICAS study and EasyOne spirometers in the PRISA study (ndd Medical Technologies; Zurich, Switzerland). These spirometers are commonly used for lung function evaluation in research studies and have been shown to maintain accuracy over time.24 BDR was evaluated using FEV1 and FVC measurements. In this study, we defined BDR by ATS criteria as a postbronchodilator increase of ≥12% and ≥200mL in either FEV1 or FVC.25 We also evaluated FEV1-specific BDR and FVC-specific BDR separately, using the same thresholds applied to each parameter independently.

Body Mass Index

In the CRONICAS study, height was measured with a stadiometer and weight with the TBF-300A (Tanita; Tokyo, Japan) body composition analyzer that includes a scale.26 In the PRISA study, weight was measured using a scale placed on a stable surface, and height was measured with a stadiometer. Both weight and height were measured twice to ensure accuracy. The main independent variable was BMI,27 calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). BMI was categorized into 4 groups: <20, 20–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30kg/m2. These categories were informed by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, which defines 25–29.9kg/m2 as overweight and ≥30kg/m2 as obesity.28 Participants with BMI <18.5kg/m2 — classified by the WHO as underweight — were included in the <20kg/m2 category. This decision was guided by the low number of individuals in the underweight range (n=46; 0.64%) and previous studies highlighting the relevance of a <20kg/m2 threshold when assessing BDR in respiratory disease populations.7

Potential Confounders

Potential confounders included sociodemographic characteristics and chronic respiratory diseases. Sociodemographic characteristics included place of origin, age, education, sex, tobacco smoking, and biomass smoke. Secondary school education or higher was defined according to each country's education law. Exposure to biomass fuel smoke was defined as the current use of biomass as the primary cooking fuel.29 Chronic respiratory diseases included COPD, asthma, previous tuberculosis, and chronic bronchitis. We defined COPD as a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC Z-score ≤ -1.645 standard deviations of the 2012 Global Lung Function Initiative mixed population reference30 and no history of asthma.7 Asthma, previous tuberculosis, and chronic bronchitis were self-reported, with asthma defined as a previous physician diagnosis, chronic bronchitis as the presence of cough with sputum production for at least 3 months per year over 2 consecutive years, and previous tuberculosis as self-reported by participants. Given that individuals with previous tuberculosis have higher rates of obstructive and restrictive lung disease compared to those without tuberculosis,31 it was considered a chronic respiratory disease.

Biostatistical Methods

The primary aim of this analysis was to study the association between BMI and BDR. Since BDR is a dichotomous outcome, we used simple and multivariable logistic regression models to calculate crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). We adjusted for sex, age group, daily smoking, secondary school or higher education, and city, that were identified through a causal diagram (Supplemental eFigure 1 in the online supplement). As a secondary analysis, we conducted a multivariable logistic regression model that included all available covariates as independent variables to assess their potential association with BDR above and beyond BMI. This model was not based on the causal diagram but aimed to explore a broader range of clinical and demographic predictors. We stratified our analyses by chronic respiratory disease status (asthma, COPD, chronic bronchitis, and previous tuberculosis). Collinearity in the adjusted models was assessed by calculating the variance inflation factor32 with a value greater than 10 indicating collinearity. In all regression models, a BMI of 20–24.9kg/m2 was used as the reference category. We tabulated categorical variables into absolute and relative frequencies and summarized continuous variables with mean and standard deviation. We used chi-square tests to compare categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to compare continuous variables between groups. The associations between BMI and FEV1 and FVC Z-scores and BDR were examined using exploratory data analyses. We calculated the difference in post- and prebronchodilator FEV1 and FVC Z-scores by each exact value of BMI, and the percentage of BDR by deciles of BMI. We conducted statistical analysis33 in R version 4.03.

Results

Participant Characteristics

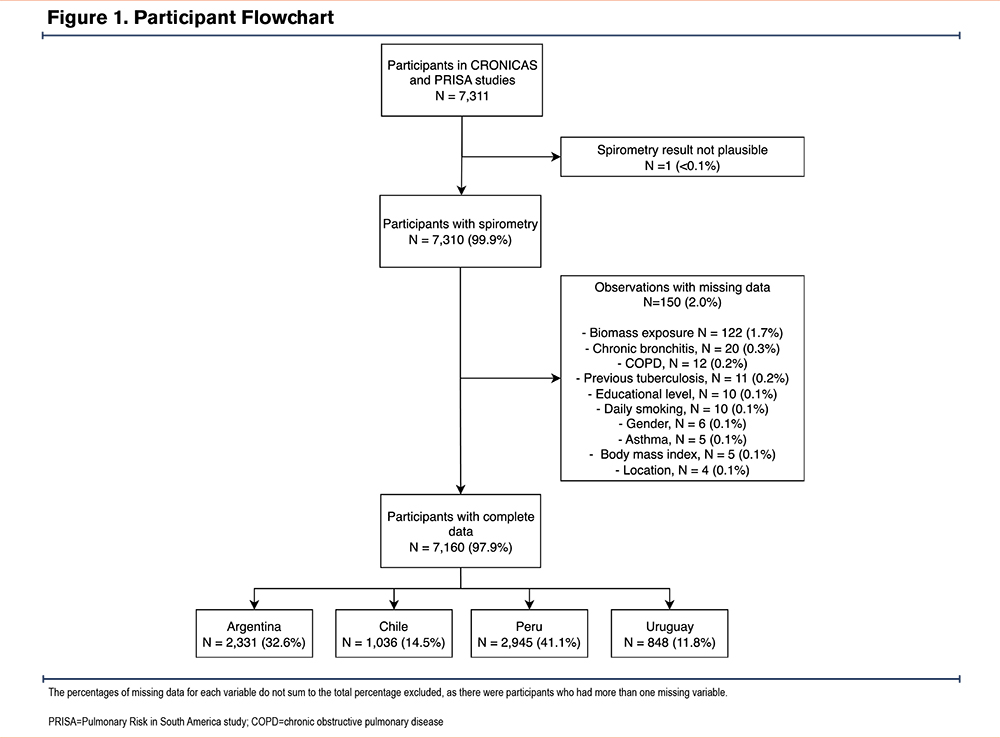

The original studies enrolled 7311 participants: 2957 from the CRONICAS study and 4354 from the PRISA study. One participant was excluded due to an implausible FEV1 value, and 150 participants (2.0%) were excluded due to missing data (Figure 1). The final sample included 7160 participants, representing 97.9% of the original cohort. The mean age was 57.3 ± 10.3 years, and 55.2% were men. A total of 23.7% had a BMI <25kg/m2, and 35.5% had a BMI ≥30kg/m2. In addition, 18.5% had a history of respiratory diseases.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Bronchodilator Responsiveness

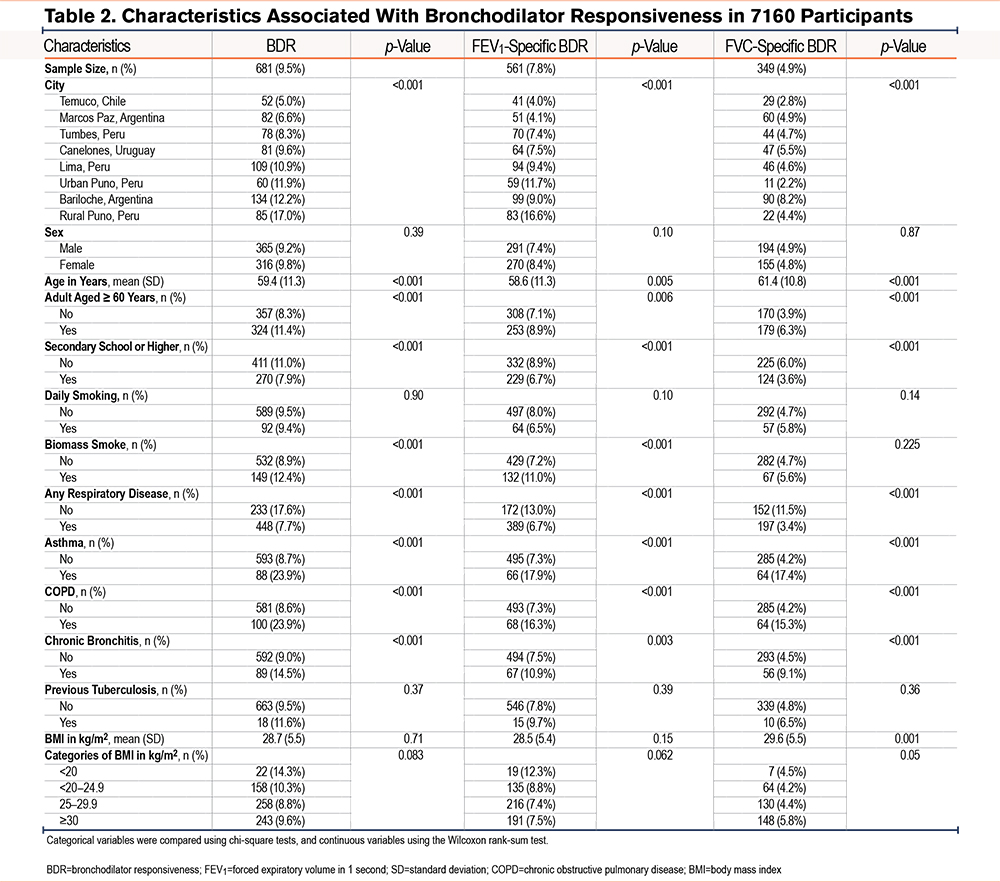

The overall prevalence of BDR was 9.5%. FEV1-specific BDR (7.8%) was more frequent than FVC-specific BDR (4.9%). Across study sites, the prevalence of BDR ranged from 5.0% to 17.0%, with the highest rate in rural Puno, Peru and the lowest in Temuco, Chile. Regarding the individual components, rural Puno had the highest prevalence of FEV1-specific BDR (16.6%), while Bariloche had the highest rate of FVC-specific BDR (8.2%) (Table 2).

In all 3 outcomes, older participants and those with a history of asthma, COPD, or chronic bronchitis had higher odds of a positive BDR compared to younger individuals. In contrast, lower prevalence was observed among those with secondary or higher education. Participants exposed to biomass smoke showed higher frequencies of BDR by ATS criteria and FEV1-specific BDR, but not FVC-specific BDR.

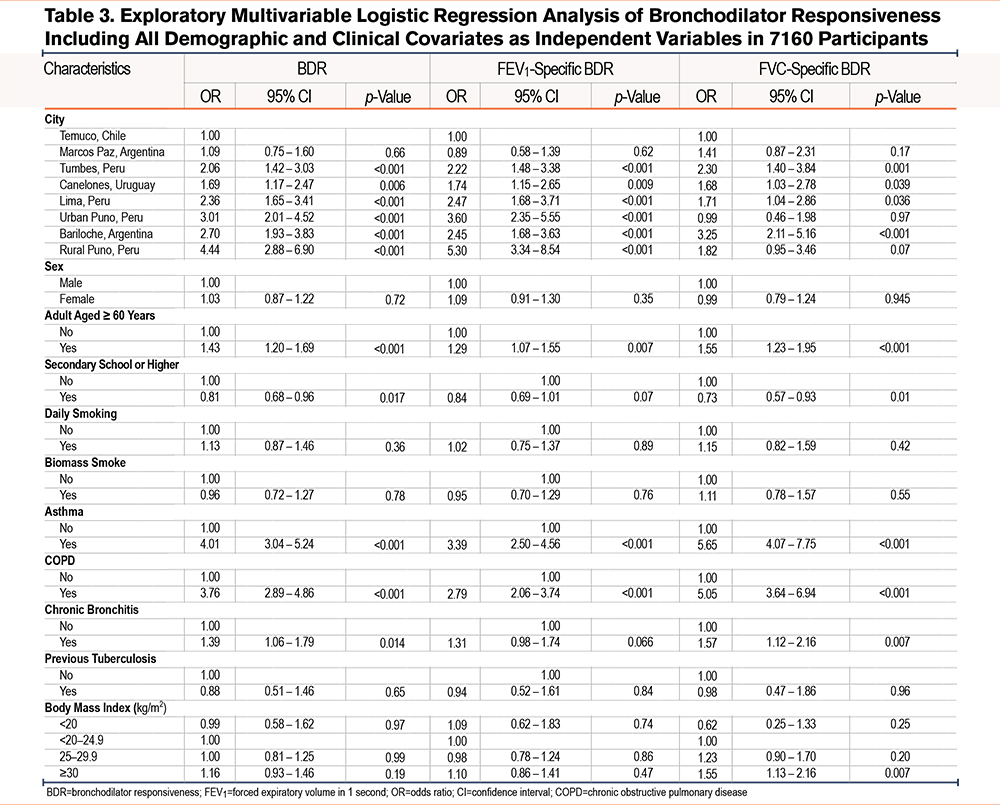

We present the results of single variable regression analysis in Supplemental eTables 1 and 2 in the online supplement. In multivariable regression models, participants aged ≥60 years had higher odds of BDR (OR=1.43, 95% CI 1.20–1.69), FEV1-specific BDR (1.29, 1.07–1.55), and FVC-specific BDR (OR=1.55; 95% CI, 1.23–1.95). Secondary school or higher education was associated with lower odds of BDR (OR=0.81; 95% CI, 0.68–0.96) and FVC-specific BDR (0.73, 95% CI 0.57–0.93). Asthma and COPD were strongly associated with all 3 outcomes. Chronic bronchitis was associated with BDR (1.39, 95% CI, 1.06–1.79) and FVC-specific BDR (1.57, 1.12–2.16), but not with FEV1-specific BDR. BMI ≥30 kg/m2 showed a significant association with FVC-specific BDR (1.55, 1.13–2.16), when compared to the reference category (20–24.9kg/m2) (Table 3).

Association Between Body Mass Index and Bronchodilator Responsiveness

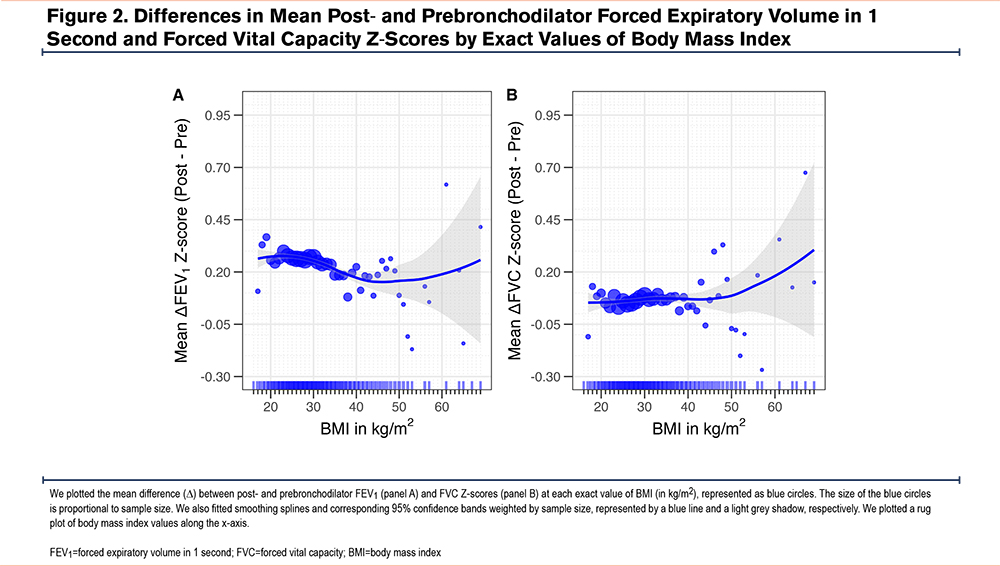

We plotted the difference between postbronchodilator and prebronchodilator Z-scores by BMI values (Figure 2). Overall, both mean postbronchodilator FEV1 and FVC Z-scores were higher than prebronchodilator values across the full BMI range. A negative trend in the mean difference between post- and prebronchodilator FEV1 Z-scores was observed between 20 and 45kg/m2. For BMI values ≥45kg/m2, the data were too sparse and variable to establish a clear pattern. In contrast, there was no consistent trend in the mean difference for FVC Z-scores across BMI values.

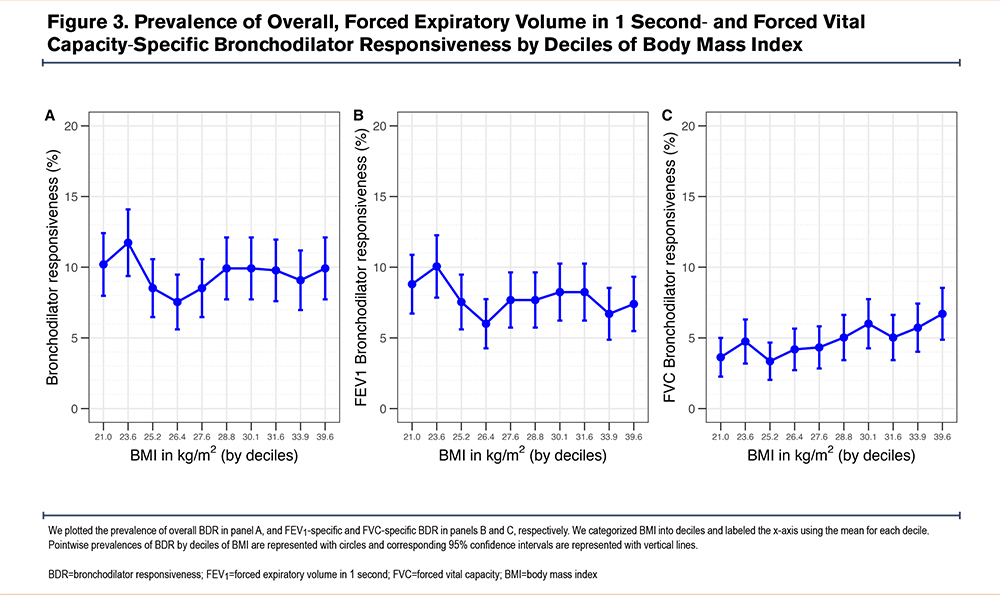

We also plotted the prevalence of BDR by BMI deciles (Figure 3). The prevalence, which averaged 9.5%, dropped to about 4% between 24 and 28kg/m2. A similar decline was observed in FEV1-specific BDR within the same BMI range. In contrast, FVC-specific BDR showed a progressive increase starting at approximately 25.2kg/m2.

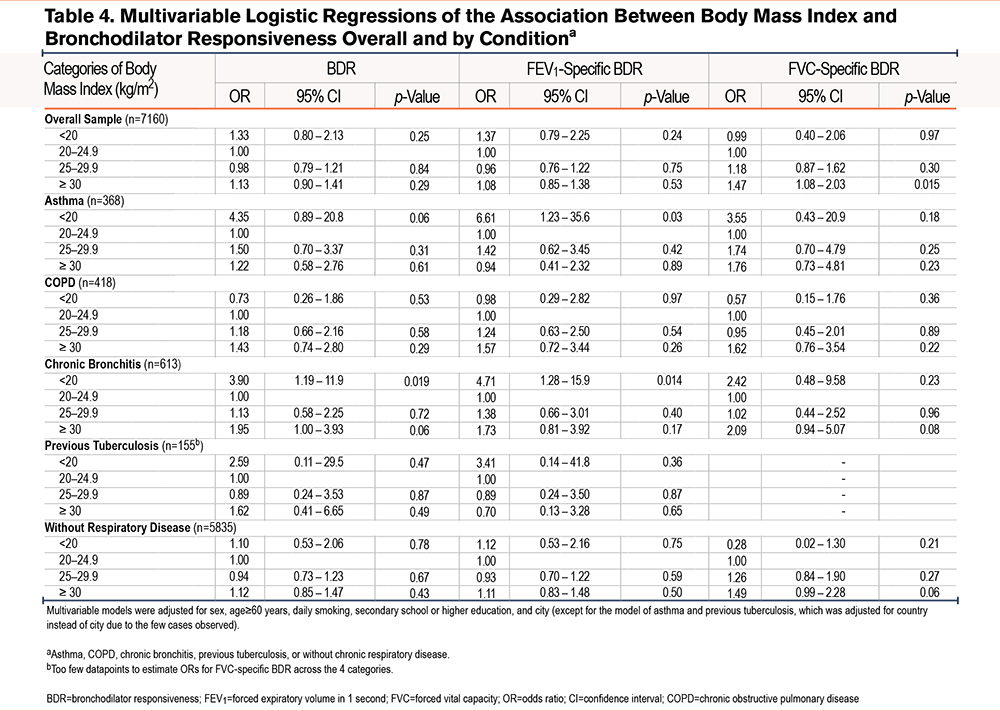

After adjusting for potential confounders, participants with a BMI ≥30kg/m2 had higher odds of FVC-specific BDR (1.47, 95% CI 1.08–2.03), compared to those with BMI 20–24.9kg/m2. In stratified analyses, participants with a BMI <20kg/m2 and asthma (6.61, 1.24–35.6) or chronic bronchitis (4.71, 1.28–15.9) had a higher odds of FEV1-specific BDR. Participants with a BMI <20kg/m2 and chronic bronchitis also had a higher odds of BDR (3.90, 1.19–11.9) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis of population-based data from 4 Latin American countries, we explored the association between BMI and BDR. We found that a BMI ≥30kg/m2 was associated with higher odds of FVC-specific BDR. In stratified analyses, a BMI <20kg/m2 was associated with higher odds of FEV1-specific BDR in participants with asthma or chronic bronchitis, and with higher odds of any BDR in those with chronic bronchitis. Older adults and individuals with obstructive respiratory diseases had higher odds of BDR. We also observed substantial variation in BDR prevalence across study sites.

Previous studies have found a positive association between higher BMI and BDR. Janson et al observed that, after adjusting for confounding variables, a BMI below 20kg/m2 was associated with lower odds (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.32–0.90) of exhibiting a postbronchodilator increase in FEV1 ≥12% and ≥200mL, compared to a BMI ≥ 20kg/m2 in participants with asthma and COPD.7In our study, we did not find an association between BMI and FEV1-specific BDR when using all the data; however, in stratified analyses we found that BMI <20kg/m2 was associated with higher odds of FEV1-specific BDR among participants with asthma and chronic bronchitis. Lehmann et al conducted another cross-sectional analysis using population-based data from Norway and found that BMI was positively associated with the percentage increase in FEV1 after administration of salbutamol.16 Yoo et al reported that the bronchodilator response measured as the percentage increase in FEV1 after administration of 200µg of salbutamol was greater in overweight or obese men compared to those with a normal BMI.15 They also reported a weak positive correlation between serum leptin levels and the percentage increase in FEV1 among men.15

The fact that we found differences in BDR when using FVC but not FEV1 supports the hypothesis that different spirometric criteria used to define BDR may capture distinct physiological changes. FEV1-specific BDR is more sensitive to changes in airflow limitation and bronchial caliber, which are typically seen in obstructive airway diseases such as asthma or COPD. In contrast, FVC-specific BDR may reflect changes related to dynamic lung volumes and hyperinflation. In individuals with obesity, reduced baseline lung volumes, early airway closure, and limited chest wall compliance may lead to incomplete exhalation during spirometry. After bronchodilator use, the reopening of previously collapsed airways and reduced air trapping can result in a greater increase in FVC, even in the absence of airflow obstruction.11 However, previous studies7,15,16have also reported associations between BMI and FEV1-specific BDR. Our stratified results suggest that such associations may become evident only in subgroups with obstructive conditions, highlighting the importance of effect modification. This discrepancy suggests that the relationship may vary across populations or study designs, highlighting the need for further research.

The prevalence of BDR was higher among participants with asthma and COPD, with both conditions showing similar prevalences of BDR, and was also higher among those with chronic bronchitis compared to individuals without these conditions. This aligns with findings from previous studies. For example, in the PLATINO study, participants with COPD had a BDR prevalence of 28%, compared to 7% in healthy individuals.10 In the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease study, BDR was 1.5 to 2 times more frequent in individuals with asthma or COPD.34 These findings suggest that the prevalence of BDR in the general population ranges between 5% and 10%, while BDR is 2 to 3 times higher in individuals with chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma and COPD. More importantly, they indicate that BDR may not be a reliable parameter to distinguish between COPD and asthma, as it occurs with similar frequency in both conditions and is not exclusive to asthma, as previously thought. Participants aged ≥60 years had approximately 43% higher odds of BDR compared to younger individuals. This is consistent with studies evaluating the association with age in different populations, including individuals with previously normal spirometry,8,9and those with asthma or COPD.7,15 Since lung function declines with age35 and BDR has been associated with worsening respiratory symptoms,7,8 these observations suggest that BDR could be a marker of both aging and chronic lung disease in the general population. Future studies could explore whether BDR is also associated with cardiovascular risk or with the likelihood of severe exacerbations in individuals with asthma, COPD, or other chronic lung diseases.36

BDR varied substantially across study sites. Most locations had a prevalence between 8% and 12%, but 2 sites, Temuco in Chile with 5% and Marcos Paz in Argentina with 7%, had lower-than-expected prevalence. In contrast, rural Puno in Peru showed a notably higher prevalence of 17%. Even within Puno, we observed a difference between rural areas with 17% and urban areas with 12%. These findings suggest that the factors influencing BDR vary considerably not only between countries but also within them. Environmental and geographic factors may partly explain this variation. However, previous studies have rarely considered this type of variability. Although we adjusted for study site to capture environmental differences, residual confounding from unmeasured exposures such as air pollution may have influenced the observed associations. These results point to the need for more precise and detailed measurements of environmental exposures to better understand their role in BDR and its relationship with BMI.

Our study also has some important strengths. We analyzed data from representative samples of multiple cities in 4 South American countries, considering diverse contexts of urbanization and altitude above sea level. Unlike previous research, our study addressed this association through a stratified approach that included both individuals with chronic respiratory disease and those without. To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide evidence of a possible association between BMI and BDR in a population without a prior diagnosis of chronic respiratory disease.

Our analysis also has some limitations. First, the analyzed study samples are not representative of the entire countries, as only 10 localities were included. Moreover, the CRONICAS study included participants aged 35 years and older, whereas the PRISA study included participants aged 45 to 75 years. Second, although we adjusted for study site, grouping data from different countries may introduce heterogeneity. These populations may differ in key environmental and social factors. Unmeasured differences, such as exposure to air pollutants and allergens, may have influenced our results.37-39 Although evidence on the relationship between BMI and environmental pollutants is still limited, it suggests potential effects on fat metabolism.40,41 Measuring environmental exposures remains complex and costly, but future studies should consider incorporating these variables to improve our understanding of the relationship between nutritional status and lung function. Third, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to assess temporality between exposures and outcomes. On one hand, it is difficult to determine when BDR developed. On the other hand, we could not account for how long participants had maintained the BMI levels observed at the time of evaluation. Although it is likely that obese individuals sustain high BMI over time,42 BMI also changes with age, usually increasing until around age 50–60 years and decreasing thereafter.43 Longitudinal studies with repeated assessments of both BMI and BDR could help clarify this association. Fourth, while BMI is a simple and widely used tool, it is not a perfect marker of obesity. It does not account for body fat distribution, muscle mass, or metabolic health. Although BMI has a moderate correlation with adipose tissue volume,44 especially in Hispanic populations, this correlation may decrease with age, particularly in men.45 Other obesity indicators may produce different results. For example, COPD has been associated with a lower BMI,46 but higher waist circumference,47,48 and studies evaluating serum leptin levels have found a positive association with BDR.15,49 Although BMI remains a practical indicator, future studies may benefit from incorporating additional anthropometric and biochemical markers. Finally, asthma was based on self-report, and COPD was defined using spirometric criteria only.

In conclusion, we found evidence that a higher BMI was associated with FVC-specific BDR, while low BMI was linked to FEV1-specific BDR in individuals with asthma and chronic bronchitis, and to overall BDR in those with chronic bronchitis. Additionally, age and a history of asthma, COPD, or chronic bronchitis were independently associated with higher odds of BDR. These findings highlight the importance of BMI and respiratory comorbidities when interpreting bronchodilator response in population-based settings.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: ANS and WC share responsibility for the conception and/or design of this analysis. WC, RHG, JJM, ABO, AR, LG, and VI share responsibility for the acquisition of data. ANS, AGL, and WC share responsibility for the analysis and/or interpretation of the data. ANS, AGL, and WC share responsibility for drafting the article and for substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission. All authors contributed significantly to the intellectual content of the article and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.