Running Head: Emphysema Detection: Diffusing Capacity for Nitric Oxide

Funding Support: None

Date of Acceptance: October 29, 2025 | Published Online: November 10, 2025

Abbreviations: AIC=Akaike information criterion; AUROC=area under the receiver operating characteristic; BH=Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; BIC=Bayesian information criterion; BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; CO=carbon monoxide; CT=computed tomography; DLCO=diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; DLNO=diffusing capacity for nitric oxide; ELPD=expected log pointwise predictive density; FDA=U.S. Food and Drug Administration; FDR=forced discovery rate; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; GAMLSS=generalized additive models of location, scale, and shape; GLI=Global Lung Function Initiative; Hb=hemoglobin; IDI=integrated discrimination index; IPD= individual patient data; IQR=interquartile range; IV=inspired volume; LR=likelihood ratio; KCO=carbon monoxide transfer coefficient; KNO=nitric oxide transfer coefficient; LASSO=least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; MCC=Matthews correlation coefficient; LOOIC=leave-one-out information criteria; NO=nitric oxide; NPV=negative predictive value; NRI= net reclassification improvement; OFF=out of fold; PC=principal component; PCA=principal component analysis; PFTs=pulmonary function tests; PPV=positive predictive value; PSiS=Pareto-smoothed importance-sampling; RBC=red blood cell; RV=residual volume; SE=standard error; SLR=segmented linear regression; TLC=total lung capacity; ULN=upper limit of normal defined as the 95th percentile; VA=alveolar volume; VIF=variance inflation factor

Citation: Zavorsky GS, Dal Negro RW, van der Lee I, Preisser AM. Emphysema detection in smokers: diffusing capacity for nitric oxide beats diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide-based models. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2025; 12(6): 500-511. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0645

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (4469KB)

Introduction

Emphysema remains a major health concern in the United States, affecting an estimated 3.8 million individuals1 in 2018, with an age-adjusted mortality rate2of approximately 9.5 per 100,000 adults in 2020. This disease destroys alveoli, compromises lung elasticity, increases air trapping, and leads to dyspnea. Chronic inflammation and progressive alveolar capillary membrane damage culminate in irreversible airflow limitation. Cigarette smoking is the primary risk factor driving lung injury.3-6 Despite improvements in diagnostics, early-stage emphysema often goes unrecognized, delaying treatment and negatively influencing clinical and quality-of-life outcomes.

Standard pulmonary function tests—such as spirometry (measuring forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], forced vital capacity [FVC], and their ratio) and pulmonary diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO)—are useful for aiding diagnosis and monitoring. However, spirometry primarily assesses airway obstruction, while DLCO is affected by pulmonary capillary blood volume and hemoglobin concentration7 and may lack sensitivity to early alveolar damage. Pulmonary diffusing capacity for nitric oxide (DLNO), first introduced in 1983–84 as abstracts,8,9 offers a more direct assessment of alveolar-capillary membrane function.10

According to the classical Roughton–Forster model, the overall resistance to gas transfer is partitioned into membrane and red blood cell (RBC) components.11 In this framework, resistance within the RBC interior is considered the principal limitation to carbon monoxide (CO) uptake (DLCO).11,12 Recent modeling work, however, indicates that DLNO is dominated by diffusion across the plasma boundary layer and reaction at the RBC surface membrane, rather than by processes within the RBC interior itself.12,13 Then, there is a completely different framework on NO and CO uptake, apart from the Roughton-Forster model. In this new framework, DLNO is interpreted as “surface absorption" dominated by the membrane-plasma path and accessible RBC surface, whereas DLCO reflects "volume absorption" that scales with engaged RBC volume and hematocrit.14,15

Regardless of which framework is ultimately correct, the NO–CO double diffusion technique remains rarely used in clinical practice, even 42 years after its introduction.8,9 While commercially available devices exist for this measurement,16 their clinical adoption is limited by a lack of clinician awareness and the absence of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for any NO-CO device. As a result, use of this method has largely been confined to research settings by a small group of specialized investigators. Given the distinct technical advantages of measuring DLNO,17 it is important for manufacturers to pursue the necessary regulatory approvals so that DLNO can become as routine as DLCO in standard pulmonary function testing.

Studies show that the alveolar uptake for NO (KNO) has better sensitivity in detecting emphysema than DLCO,18 and that summed DLNO+DLCO z-scores outperform DLCO z-scores alone in model performance, predictive accuracy, and classification scores.7,19 DLNO and KNO also correlate more closely with computed tomography (CT) markers of emphysema better than DLCO or the carbon monoxide transfer coefficient (KCO).20,21 By enabling earlier and more accurate detection of emphysema, DLNO could facilitate timely, targeted interventions. Early identification of disease is clinically important, as patients with undiagnosed COPD face poorer outcomes and reduced quality of life22 while early diagnosis and management can reduce health care utilization and improve quality of life.23 Detecting emphysema before substantial functional decline enables timely, evidence-based interventions—such as risk stratification, smoking-cessation support, pulmonary rehabilitation, and individualized care—that can slow disease progression and reduce emphysema progression in quitters.24 Pulmonary rehabilitation, in particular, improves exercise tolerance, reduces dyspnea, and enhances quality of life.22,25,26

This study examines DLNO’s diagnostic performance, accuracy, and classification ability in emphysema patients compared to DLCO, spirometry, and lung volumes. Using a large cohort—predominantly smokers—from 3 hospital centers, we applied z scores derived from established reference equations.27-31 We hypothesized that DLNO and DLCO z scores would outperform conventional metrics in diagnosing emphysema. If DLNO proves more accurate, it could be adopted routinely alongside DLCO. This adoption could facilitate earlier diagnosis, improve patient-centered outcomes, and stimulate the development and regulatory approval of accessible DLNO measurement equipment—overcoming current technological and logistical barriers.16

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted an individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis pooling raw, participant-level data to harmonize variables, standardize analyses, and increase precision.32 The pooled dataset included 496 White participants (mostly smokers; interquartile range 6–43 pack years): 126 with computed tomography (CT)–confirmed emphysema and 370 without, from 4 European hospital centers.18,33-35 After harmonization, 3 centers were retained because they consistently used the simultaneous 10-second NO–CO protocol NO–CO testing18,33,34; all 4 source datasets remain available in a public repository.36 All original studies had ethics approval; this de-identified secondary analysis did not require additional review.

Data Collection, Conversion, and Quality Control

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) followed American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines,37-39 measuring DLNO, DLCO, alveolar volume (VA), KCO, and KNO with a 10 ± 2-second breath-hold time (denoted DLNO10s, DLCO10s, VA10s, KCO10s, and KNO10s). Lung function variables were converted to z-scores using Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) reference equations for spirometry,28 lung volumes,27 and DLCO10s,29 adjusting for age, sex, and height. For the NO-CO double diffusion technique, z-scores were derived from reference equations developed with 10-second breath-hold maneuvers30 and from equations that account for between device variability.31,40 Because available DLNO reference equations were derived in White cohorts30,31and genetic ancestry influences DLNO,41-43 analyses were restricted to White participants.

Study-level quality was graded across 9 items: (1) inclusion of COPD and non-COPD participants, (2) pack years, (3) radiologist-adjudicated CT emphysema (% volume), (4) smoking history, (5) modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale, (6) sex, (7) height, (8) weight (coded “not provided” if imputed), and (9) technical quality control. Technical failure criteria were breath-hold outside 8–12 seconds; VA/total lung capacity (TLC) >1.0; FEV1/FVC ≥1.0; residual volume (RV)/TLC <0.20; or inspired-volume (IV) to FVC (IV/FVC) <0.85. Studies with <5% failures met technical standards. The RV/TLC <0.20 rule excluded physiologically implausible values. A summary score (0–9) tallied the 8 availability items plus the quality control flag (Table S1 in the online supplement). R packages are listed in Tables S2–S3 in the online supplement.

Model Discovery and Comparator Definition (Post-Selection)

We assembled 34 candidate logistic models from clinically plausible and data-driven combinations of z-scores (FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, TLC, RV/TLC, VA, DLCO10s, KCO10s, DLNO10s, KNO10s). To encourage parsimony, we screened with least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and ranked all candidates using Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Pareto-smoothed importance-sampling—leave-one-out information criterion (PSIS-LOOIC) on the analysis dataset (lower values indicate superior expected out-of-sample fit and parsimony). Guided by this screening, we defined 3 focal comparators for all downstream evaluation:

Model A: TLC z-scores + FEV1 z-scores + DLCO10s z-scores

Model B: Model A + DLNO10s z-scores

Model C: TLC z-scores + FEV1 z-scores + DLNO10s z-scores

TLC, FEV1 and DLCO10s z-scores were fitted using GLI equations27-29 and DLNO z-scores were fitted using generalized additive models of location, scale, and shape (GAMLSS) reference equations of Zavorsky and Cao.31

This workflow is data-adaptive/post-selection: information-criterion screening of individual/summed predictors informed LASSO model building, and all candidates were ultimately compared on the same information criterion scale before selecting Models A–C.

Objectives, Endpoints, and Hypotheses

Based on the results above, a primary objective was to test whether the parsimonious 3-predictor DLNO10s model (Model C) is noninferior to the analogous DLCO10s model (Model A) for detecting CT-defined emphysema in adult smokers, compared to smokers without emphysema, while achieving better parsimony/generalizability. A key secondary objective was to assess whether adding DLNO10s to Model A (which is Model B) or expanding to higher-dimension variants yields clinically meaningful gains over Model C after accounting for complexity.

The primary endpoint was out-of-fold (OOF) Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) on held-out folds, using thresholds learned via Youden’s J in training and applied to the paired test fold (MCC family under Benjamini–Hochberg [BH] control for prespecified contrasts). Another endpoint was the BIC and PSIS-LOOIC computed on the analysis dataset to quantify parsimony/generalization.

Secondary endpoints included the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) in the test folds (threshold-free discrimination), decision curve analysis net benefit across risk thresholds of 0–0.25, and a set of threshold-based performance metrics—accuracy, balanced accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), F1 score, Cohen’s kappa, false positive rate, false negative rate, false discovery rate (FDR), positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR−), and the diagnostic odds ratio—each calculated out-of-fold at the Youden-derived threshold. Exploratory endpoints included category-free net reclassification improvement (NRI), integrated discrimination improvement (IDI), calibration intercept and slope with bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs), principal component analysis (PCA) loadings and variance explained, and hierarchical partitioning of McFadden’s R2.

The primary hypothesis was that Model C is noninferior to Model A on OOF, MCC, and AUROC and shows lower BIC and/or PSIS-LOOIC (i.e., superior parsimony/generalization). The secondary hypotheses were that Model B and higher-numbered variable models do not provide clinically meaningful gains in OOF performance or decision-curve net benefit over Model C once complexity penalties are considered.

Decision Rules, Inference, and Multiplicity

For each contrast we estimated ΔMCC and ΔAUROC using paired, fold-level bootstrap (10,000 resamples); 2-sided bootstrap p-values were computed, with BH control applied only within the MCC family across contrasts. Parsimony/generalization superiority was judged by BIC/PSIS-LOOIC (with |Δ| ≥ 2 typically indicating a small but nontrivial improvement). Secondary and exploratory endpoints were interpreted descriptively without alpha allocation.

Model Fitting, Selection, and Internal Validation

Logistic models were initially fit as generalized linear mixed models with a study-level random intercept; model fit and diagnostics favored generalized linear models without the random intercept for 8/34 models, which were used for primary analyses (Table S10 in the online supplement). Primary selection used BIC; expected out-of-sample performance used PSIS-LOOIC. Discrimination used AUROC with 95% CIs (BH-controlled where applicable). We applied stratified 10-fold cross-validation × 1000 repeats with within-fold standardization; thresholds were learned in training and applied to held-out folds. OOF probabilities were averaged across repeats; each model’s global threshold was the mean of fold-level Youden-J thresholds. Uncertainty used paired, fold-level bootstraps; decision-curve analysis assessed standardized net benefit.

Ancillary and Rank-Based Analyses

PCA assessed latent structure/collinearity. Hierarchical partitioning decomposed McFadden’s R2 into unique and joint components for FEV1, TLC, DLCO10s, and DLNO10s z-scores. Reclassification (category-free and threshold-based NRI, IDI) compared Models B−A and Models C−A. Calibration used logistic recalibration (intercept α, slope β) with bootstrap CIs and calibration plots. Sensitivity analyses included alternative operating points and leave-one-center-out checks.

To synthesize signals across metrics, we performed rank-based comparisons of MCC, AUROC, BIC, and PSIS-LOOIC across the top 10 models.

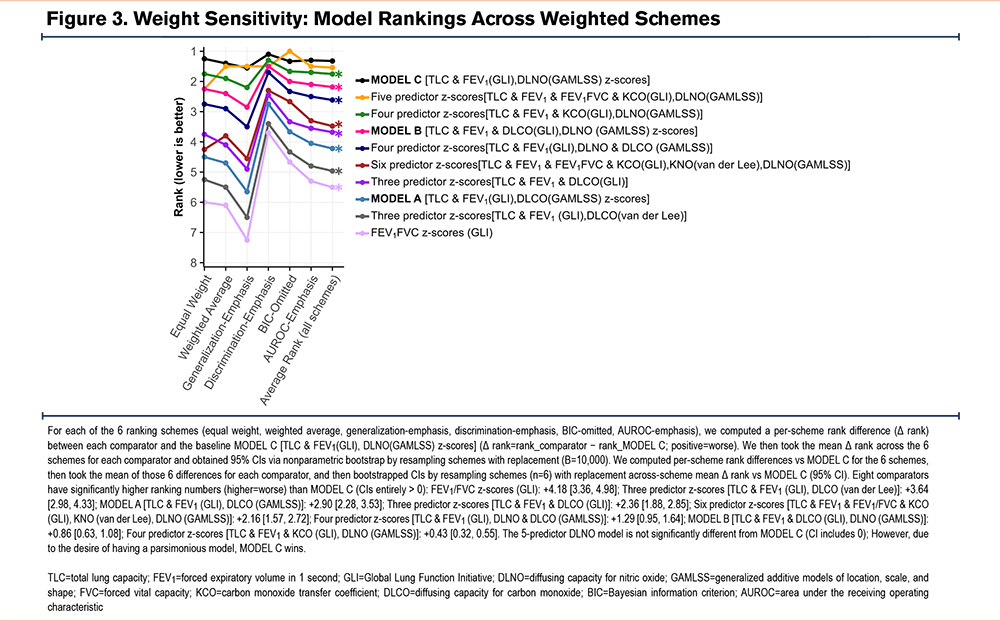

To assess whether model comparisons were robust to the weighting of evaluation metrics, we prespecified 6 ranking schemes (equal weight, weighted average, generalization emphasis, discrimination emphasis, BIC omitted, and AUROC emphasis). For each comparator, we computed the rank difference (comparator – the best ranked model) within each scheme and then the mean Δ rank across schemes. To reflect sensitivity to weighting choice, we obtained 95% bootstrap intervals by resampling schemes (n=6) with replacement (B=10,000) and recomputing the across scheme mean. We did not resample the derived “average rank” column. Instead, intervals were based on the 6 scheme specific differences. Intervals entirely >0 indicate the comparator is consistently ranked worse than Model C across the prespecified schemes.

Statistical Software

Analyses were performed using RStudio (2025.09.0), Build 387, with R (version 4.4.2). Two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additional information on the statistical analyses can be found in the online supplementary material in the Supplementary Methods section, and Tables S1 to S9.

Results

Participant Characteristics

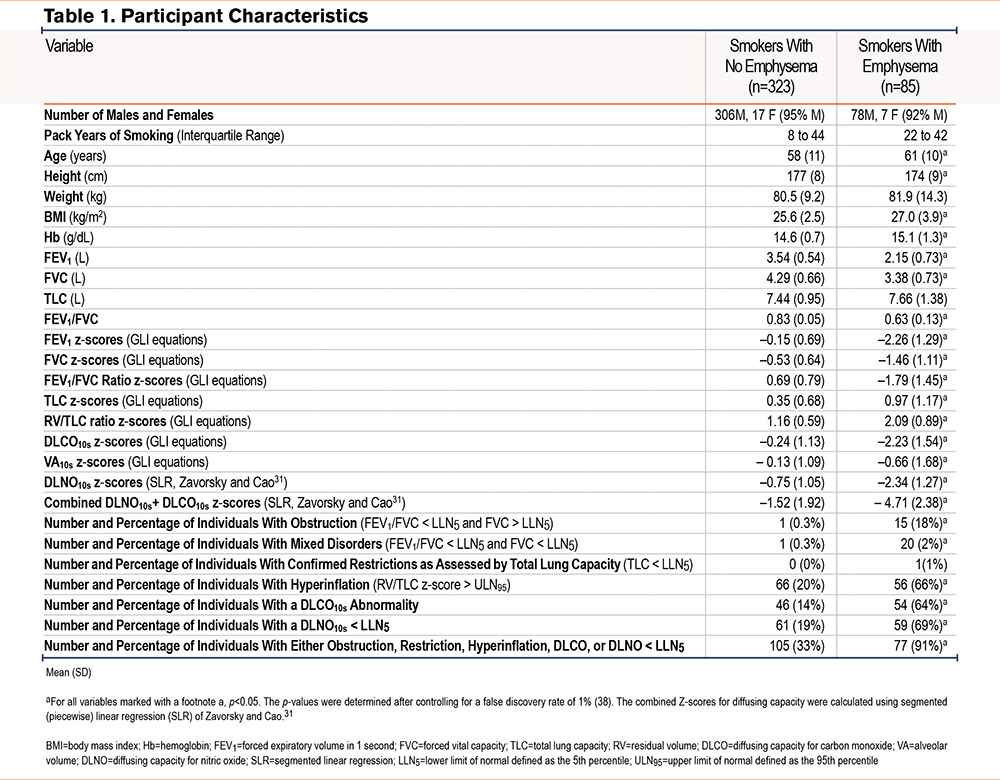

Of 496 eligible individuals, 408 (85 emphysema, 323 controls) met harmonization and quality control criteria (See Table S1, Figure S1 in the online supplement). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median breath-hold time for diffusing capacity was 10 seconds (interquartile range [IQR], 9.2–10). The median DLNO10s/DLCO10s ratio was 4.43 (IQR 4.09–4.88) for emphysema and 4.50 (IQR 4.22–4.84) for non-emphysema (p=0.226). Nearly all variables in Table 1 were statistically different between the 2 groups except for pack years of smoking and the proportion of participants with pulmonary restriction. The pooled data demonstrate that 71% of the variance in DLNO10s z-scores is shared with DLCO10s z-scores (Figure S2 in the online supplement).

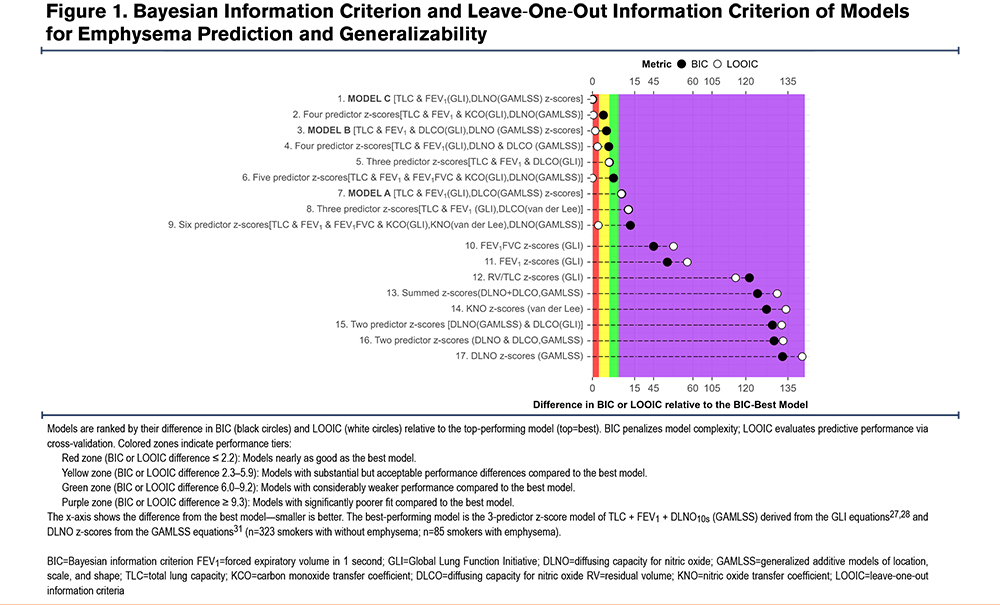

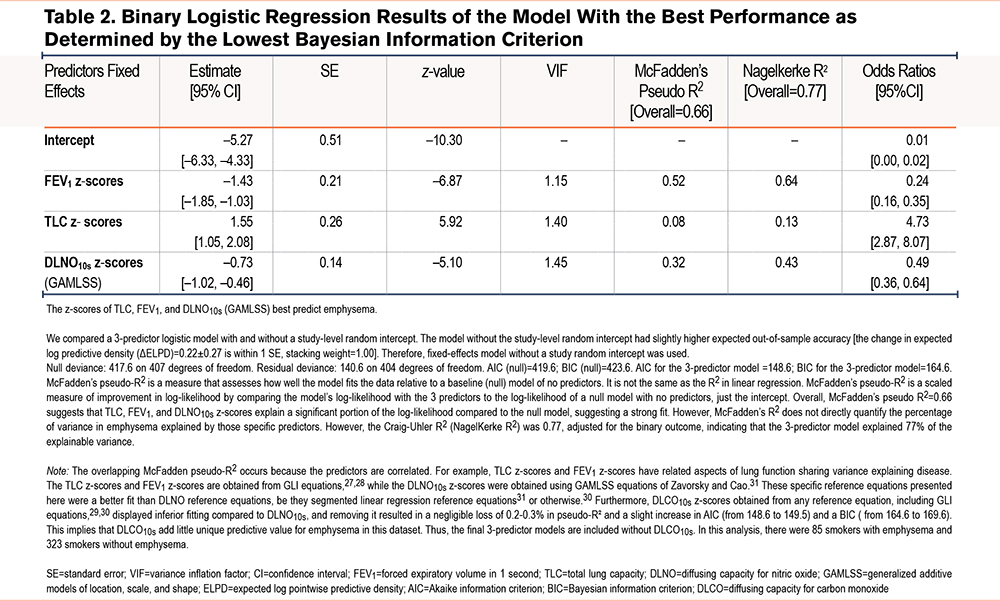

Information Criteria and Generalization

The top 17 models are ranked by their difference in BIC and LOOIC relative to the top-performing model (Figure 1). The bottom 18 models are presented in Figure S3 in the online supplement. Absolute values for BIC and LOOIC for all 34 models are presented in Table S10 in the online supplement. A compact cluster—including the 3-predictor DLNO model (Model C)—lies near Δ0 for both BIC and LOOIC. Single-index models (e.g., VA alone, DLCO alone) are markedly inferior to the multiple variable predictor models. As such, the model with the lowest BIC is presented in Table 2 with the AUROC, and its precision-recall curves are presented in Figure S4 in the online supplement.

Discrimination Area Under the Receiving Operating Characteristic and Matthews Correlation Coefficient at the Youden Cut-Point

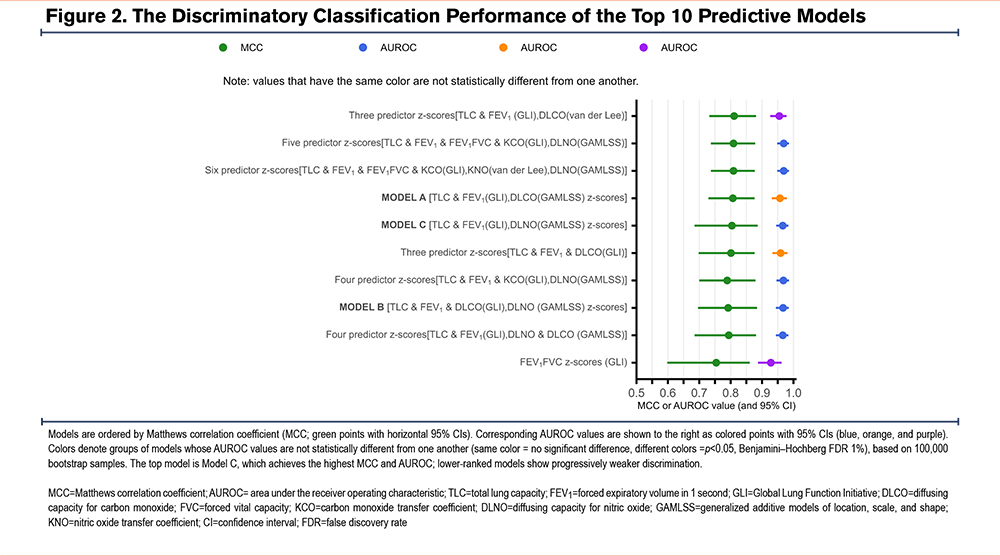

Figure 2 displays MCC (bars) and AUROC (points with 95% CIs) ranked by MCC at the Youden threshold for the top 17 models. The bottom 17 models are presented in Figure S5 in the online supplement. Three- to 6-predictor DLNO models achieve AUROC ≈0.96–0.97 with MCC ≈0.8. Model A (DLCO-based) is modestly worse, and Model B (A + DLNO) trades sensitivity and specificity without clear net gain (for fold-averaged metrics and CIs).

Principal Component Analysis and Hierarchical Partitioning

PCA revealed principal component (PC) 1 (gas transfer: DLNO/DLCO), PC2 (hyperinflation: TLC/VA), and PC3 (obstruction/air-trapping: FEV1/FVC, RV/TLC) (Tables S11–S13 in the online supplement). PC4 was not found to add any benefit (Table S14, Figure S6 in the online supplement). Replacing z-score predictors with PC1–PC3 did not improve discrimination or generalization (ΔAUROC ≈0–0.01; ΔLOOIC/ΔBIC <2); hence, we favor Model C (TLC + FEV1 + DLNO z-scores) specification for interpretability. Hierarchical partitioning ranked unique contributions as the FEV1 z-scores >DLNO10s z-scores >TLC z-scores >DLCO10s z-scores (Tables S15–S16 in the online supplement).

Classification, Reclassification and Decision Analysis

Model B z-scores (FEV1, TLC, DLNO10s, DLCO10s z-scores) or Model C (z-scores FEV1, TLC, DLNO10s, z-scores) compared to Model A (FEV1, TLC, DLCO10s z-scores) demonstrated no real difference in 17 metrics when considering the 95% CI (Tables S17–S18 in the online supplement). At Youden-optimized thresholds, the overall net improvement in reclassification when DLNO10s is added to the Model A was not significant. However, the average predicted risk-gap between predicting smokers with and without emphysema improved by as much as 5% when DLNO10s is added to Model A (Table S19 in the online supplement).

At category-free reclassification, there was a 34% overall net improvement in reclassification (95% CI = -12 to 96%) when DLNO10s was added to Model A. Simply, this means that, compared with the old model, the new model moved people in the right direction (up for true cases, down for true noncases) 34 percentage points more often than it moved them in the wrong direction. Moreover, the average predicted risk-gap between predicting smokers with and without emphysema improved by as much as 5% when DLNO10s was added to Model A (Table S20 in the online supplement).

Decision-curve analysis using out-of-fold predictions (Figure S7 in the online supplement) showed all 3 models (Models A, B, C) delivered positive net benefit across threshold probabilities 0–0.25, exceeding Treat None and—apart from the very lowest thresholds—exceeding Treat All. The Treat-All curve crossed zero at ~0.21 (cohort prevalence), while all model curves remained positive. The e curves overlapped closely; the 4-predictor model (Model B) offered no discernible advantage over either Model A or C. Absolute net benefit was ~0.16–0.20, i.e., ~16–20 more correctly flagged smokers with emphysema per 100 smokers than doing nothing, at thresholds 0–0.25

Model Rankings

Across schemes, 8 out of 9 comparators ranked significantly worse than the best ranked model (Model C, Δ rank > 0; 95% CI is >0). The 5-predictor DLNO model was the only top 10 model that had a ranking that was not different to Model C. (Δ=+0.22 [−0.09, 0.57]). As such, Model C (TLC z-scores, FEV1 z-scores, and DLNO10s z-scores) offered near-top performance yet delivered comparable discrimination/generalization with fewer predictors with greater parsimony than any other model. Thus, Model C is the best choice (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our multicenter IPD meta-analysis demonstrates that compact models incorporating DLNO offer robust, high-quality classification of emphysema compared to smokers without emphysema. In the 3-predictor DLNO z-score model (Model C: TLC z-scores, FEV1 z-scores, and DLNO10s z-scores), the TLC z-scores and FEV1 z-scores were obtained using GLI equation for White participants,27,28 while the best fitting DLNO z-scores were obtained by using the DLNO GAMLSS equation from Zavorsky and Cao.31 The 3-predictor DLNO z-score model (Model C) occupied a consistently superior or cosuperior position across BIC/LOOIC (Figure 1) and AUROC/MCC (Figure 2) and maintaining top ranks across weighting scenarios (Figure 3).

The incremental advantage in Model C (TLC z-scores, FEV1 z-scores, and DLNO10s z-scores) versus a DLCO-based analogue (Model A) is modest, but consistency across metrics and resampling supports a genuine performance edge for Model C. Reclassification indices were small (Tables S19–S20 in the online supplement), suggesting DLNO’s benefits manifest more as improved overall performance and calibration (Figure S7 in the online supplement) than as wholesale shifts in categorical assignment at a single threshold.

The pooled data demonstrate that 71% of the variance in DLNO10s z-scores is shared with DLCO10s z-scores (Figure S2 in the online supplement) displaying substantial collinearity; yet the residual ~29% “unique” variance is not necessarily predictive for emphysema. Nevertheless, adding DLCO z-scores to Model C, model barely changes performance (McFadden’s R2=0.663 → 0.666; and BIC worsens), and AUROC gains were negligible. That is strong evidence that the “unique” DLCO portion does not add a meaningful predictive signal for emphysema beyond the z-score model of TLC + FEV1 + DLNO10s z-scores.

Physiologic plausibility of the results is strong. One view is that NO uptake primarily reflects membrane resistance, whereas CO uptake reflects the resistance that occurs within the red cell membrane (Zavorsky et al Figure 1).7 The finding that adding DLCO z-scores to a DLNO z-score-based model contributes little, coheres with early membrane-dominant injury in emphysema. PCA structure (Tables S11–S14 in the online supplement) and hierarchical partitioning (Table S15–S16 in the online supplement) further support construct validity by aligning dominant components with expected physiologic domains.

In our IPD meta-analysis, Model C had similar discrimination and classification of the 3-predictor model using TLC, FEV1, and DLCO10s z-scores, while achieving lower BIC and LOOIC—indicating a more parsimonious specification with better expected out-of-sample fit. Practically, this suggests DLNO10s can substitute for DLCO10s as the gas-transfer input in emphysema when simultaneous NO–CO testing is available, and quality control is assured. We are not advocating DLNO10s in isolation from spirometry and lung volumes across all pathologies – summed DLNO+DLCO z-score models can outperform either measure alone in other conditions.19,7 Rather, among transfer measures, DLNO10s alone (without DLCO10s) appears sufficient in this emphysema-screening context. DLCO10s still has broader clinical roles (e.g., interstitial lung44,45and pulmonary vascular disease46) so laboratories without NO–CO capability can continue to rely on DLCO10s, whereas centers with NO–CO may reasonably prioritize DLNO10s or DLNO5s, where validated, in parsimonious models. Decision-curve analyses indicate potential utility at low thresholds common to screening/case-finding (Figure S5 in the online supplement).

Despite promising diagnostic performance, DLNO remains underutilized since its introduction8,9 in 1983-84, largely due to limited awareness, regulatory hurdles, and the high cost of sensitive NO analyzers. DLNO testing is available as an add-on to DLCO on at least one commercial platform (e.g., MGC Diagnostics; St. Paul, Minnesota), requiring only an NO sensor, cylinder, and minimal training. These systems typically use low-cost electrochemical sensors (e.g., 7NT CiTiceL®), but their limited range (0–100 ppm) and slow response (~15 second) make them unsuitable for longer breath-holds where exhaled NO concentrations drop below detectable thresholds. Chemiluminescence remains the gold standard for NO detection due to its rapid response (<1 second) and wide dynamic range (1 ppb–100 ppm), but devices like the CLD 855 Yh (Eco Physics; Ann Arbor, Michigan) cost ~$35,000 USD. Mass production could lower this to $10,000–$21,000 per unit if adopted across the estimated 2000–5000 DLCO-equipped sites in the United States.47

Moreover, the similar median DLNO10s/DLCO10s ratios between emphysema and non-emphysema groups (4.43 versus 4.50) suggest that raw ratios lack discriminatory power—reinforcing the need for z-score standardization in diagnostic models. Future work should prioritize affordable, regulatory-approved DLNO10s systems and longitudinal studies to assess their clinical utility.

Limitations

Our pooled analytic sample comprised primarily White adults who were current or former smokers from European centers using a 10 ±2-second simultaneous NO–CO protocol; only ~14% were never-smokers. Accordingly, generalizability to never-smokers, other ancestral groups, pediatric or very elderly populations, and to laboratories using different devices or protocols may be limited. CT-confirmed emphysema improves case specificity but may miss early/subclinical or airway-predominant disease. Although we harmonized variables across sites, applied uniform quality control, and used repeated cross-validation with leave-one-center-out checks and calibration assessment, we lacked an independent external cohort; thus, performance estimates and optimal thresholds may shift in other settings. Furthermore, it is known that genetic ancestry affects DLNO,41-43 so standardization relying on DLNO reference equations and GLI equations for TLC and DLCO derived largely from White cohorts, can constrain calibration and promote bias. Reference equations developed for specific genetic ancestries (versus only White) are needed to maintain precision. We also lacked uniform data on comorbidities, medications, and socioeconomic context, limiting adjustment for potential confounding and spectrum effects. Finally, the dataset did not include longitudinal outcomes (e.g., exacerbations, CT progression, mortality), so we evaluated discrimination and reclassification rather than long-term clinical impact; strict and complete-case analysis may also introduce selection bias, and residual site/device effects may persist despite adjustment.

Broader Implications for Diffusing Capacity for Nitric Oxide Adoption in Clinical Practice

The demonstrated superiority of DLNO10s z-scores in predicting and classifying smokers with emphysema compared to smokers without emphysema offers a compelling case for DLNO inclusion in routine pulmonary function testing. Despite the current barriers to widespread adoption—such as the high cost of NO analyzers and regulatory hurdles—this study provides strong evidence for the clinical value of DLNO. Its ability to detect subtle changes in alveolar-capillary membrane functionality positions it as a critical tool for early COPD diagnosis, particularly in high-risk populations such as smokers.

Future efforts should focus on developing cost-effective, FDA-approved devices for DLNO measurement to facilitate its integration into pulmonary function laboratories. Additionally, prospective studies validating these findings in diverse populations are necessary to further establish DLNO's role as a diagnostic benchmark.

Conclusion

The 3-predictor model incorporating DLNO10s z-scores with TLC z-scores and FEV1 z-scores offers superior model performance, predictive accuracy, and classification for emphysema detection compared to DLCO10s-based models. These findings advocate integrating DLNO10s into routine clinical practice, potentially improving early diagnosis and patient outcomes in emphysema management.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: GSZ was responsible for the conceptual design of the work, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, visualization, and original and final draft preparation. RWD-N, IvdL, and AMP provided the study participants and data collection and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript submitted for publication.

Data sharing statement: The data supporting this study's findings are accessible on Mendeley Data,36 a cloud-based repository for research data.

Declaration of Interest

GSZ is a GLI Network member. The GLI Network has published reference equations for spirometry, DLCO, and static lung volumes using GAMLSS models. GSZ is the current cochair of the European Respiratory Society Task Force on the interpretation of DLNO. The remaining authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.