Running Head: Determinants of Medication Nonadherence in COPD

Funding Support: This study was supported by American Thoracic Society/American Lung Association/CHEST Foundation Respiratory Health Equity Award, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and National Institutes of Health through grant award numbers KL2TR002002 and UL1TR002003.

Date of Acceptance: January 1, 2026 | Published Online Date: January 12, 2026

Abbreviations: COM-B=Capability, Opportunity and Motivation model of Behavior; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; INR=international normalized ratio; SES=socioeconomic status; TDF=Theoretical Domains Framework

Citation: LaBedz SL, Okpara EM, Potharazu AV, Joo MJ, Press VG, Sharp LK. Determinants of medication nonadherence among diverse adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2026; 13(1): 73-83. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0673

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (256KB)

Introduction

Less than 50% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are adherent to inhaled long-acting bronchodilators and corticosteroids despite the known efficacy of these medications.1-3 Nonadherence to COPD medications is linked to poorer quality of life, higher health care costs, and greater risk of hospitalization and death.4-6 Studies suggest that minority race and lower socioeconomic status (SES), among other factors, are associated with nonadherence.7-9

The drivers of nonadherence behavior in COPD, particularly amongst vulnerable populations, remain poorly understood. Existing conceptual models of medication adherence in other chronic diseases10 offer insight into drivers of nonadherence but fail to capture factors distinctive to COPD and inhaler therapy. While some quantitative studies have identified predictors of COPD nonadherence such as disease severity11 and inhaler type,12 they fail to explain the pathways or mechanisms that lead to nonadherence behavior.

Improving COPD medication adherence will require interventions that are grounded in behavioral change theory13 and guided by a conceptual model of adherence specific to COPD. The Capability, Opportunity and Motivation model of Behavior (COM-B), together with its associated Behavioral Change Wheel, is a widely used behavioral framework for comprehensively identifying mechanisms that contribute to a behavior and specifying the types of interventions likely to effectuate behavior change.14 According to the COM-B model, behavior is determined by the interplay of physical and psychological capabilities, physical and social opportunities, and reflective and automatic motivations. Using qualitative methods and the evidence-based COM-B model, this study aimed to systematically identify barriers and facilitators most likely to influence adherence among a predominately minority and low SES population with COPD.

Methods

Participants were recruited from a single academic medical center in Chicago, Illinois and screened for eligibility criteria using electronic health records. Participants had to be aged >40 years with: (1) a diagnosis of COPD (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision and/or physician-diagnosed); (2) an active prescription for a long-acting beta agonist or long-acting muscarinic antagonist inhaler; and (3) a forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity < 0.70 on postbronchodilator spirometry. Those who met eligibility criteria were mailed recruitment letters inviting them to participate in the study or were approached in person as they sought routine medical care. Potential participants who had a previous or current clinical relationship with the investigator conducting the interviews (SL) were not recruited. We employed purposive sampling to maximize heterogeneity with respect to age, sex, race/ethnicity, airflow obstruction severity, SES indicators, and previous encounters with a pulmonologist. Recruitment continued until thematic saturation was achieved (i.e., no new themes or insights emerged from the data), and the sample was sufficiently diverse.

After providing verbal informed consent, in-depth telephone interviews were conducted using a standardized semistructured interview guide (Supplemental Appendix in the online supplement). Questions were informed by the major domains of the COM-B model14 and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF),15 with additional probing questions used as needed to explore emerging themes. The first 5 participants enrolled in the study were considered pilot participants to test the comprehensibility of the interview guide. If a participant asked for clarification or gave an inadequate response to a question, the question was reviewed by investigators and modified as needed to improve clarity. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Thematic analysis of interview transcripts took place concurrently with data collection. Three investigators (SL, AP, EO) developed a preliminary codebook using 4 exemplar interviews selected for their depth and breadth of themes. The preliminary codes were largely based on the domains of the TDF with additional codes generated to capture more nuanced aspects of inhaler use behavior identified in the interviews. Two investigators (SL, EO) independently coded these interviews, meeting regularly with a third investigator (LS) to compare coding and refine code definitions. After reviewing 9 additional interviews for emerging themes, the coding team reached a shared understanding of the codes and finalized the codebook (Supplemental Appendix in im the online supplement). Two investigators (SL, EO) independently coded the remaining interviews using NVivo (version 14, Lumivero; Denver, Colorado), met regularly to compare codes and reconcile discrepancies, and consulted with an expert reviewer (LS) to reach consensus.

The University of Illinois Chicago institutional review board approved the study protocol. Results were reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist16 (Supplemental Appendix in the online supplement).

Results

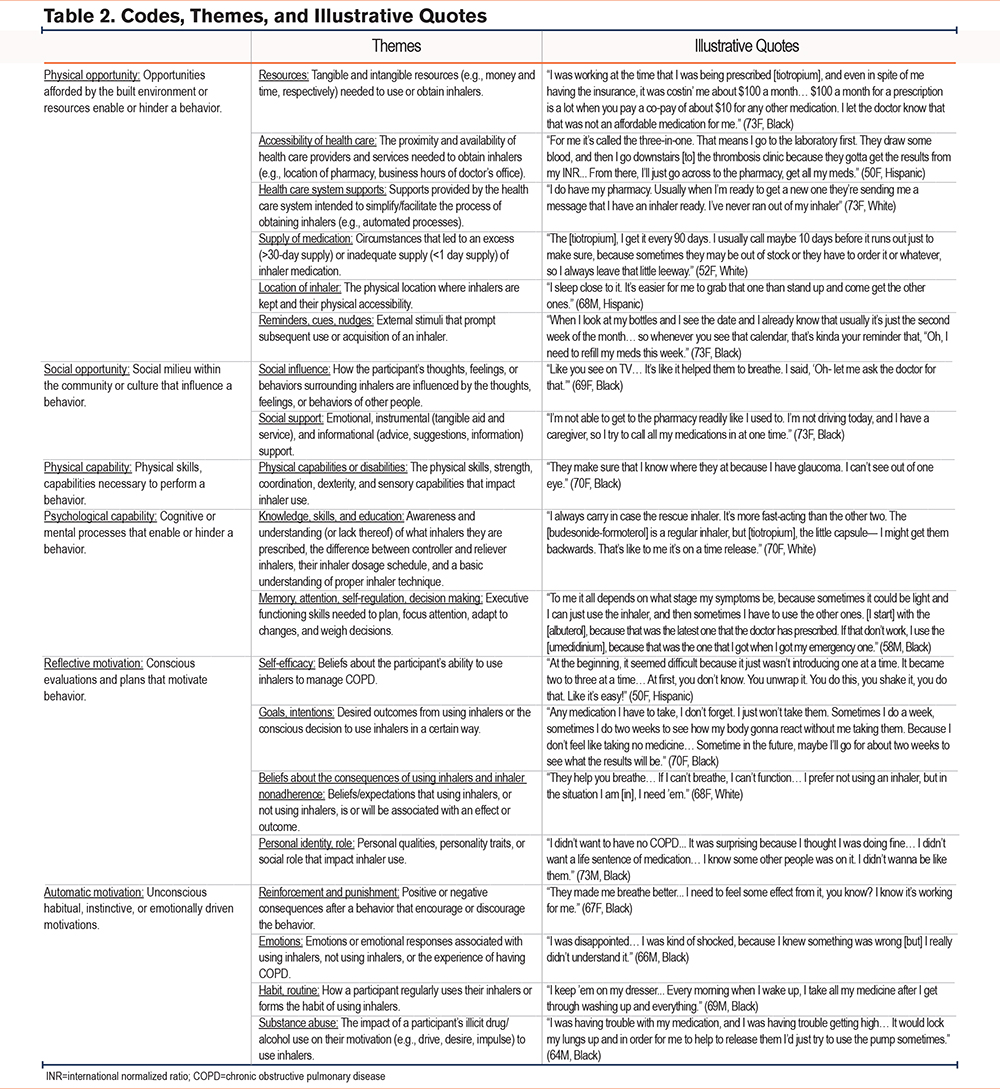

Of the 17 individuals who completed interviews from September 2023 to June 2024, 10 (59%) identified as non-Hispanic Black, 4 (24%) identified as non-Hispanic White, and 3 (18%) identified as Hispanic. Most participants received the equivalent of a high school education or less, reported an annual household income of <$30,000/year, and had at least one previous encounter with a pulmonologist (Table 1). Nearly half of participants reported using their inhalers differently than prescribed. One interview was excluded from the analysis due to poor audio quality. We identified several themes of barriers or facilitators to inhaler adherence (Table 2).

Physical Opportunity

Physical opportunity refers to the built environment and resources that enable or hinder participants using or obtaining an inhaler. These included having money, health insurance, accessible health care services, the health care infrastructure, and physically possessing an inhaler with adequate medication. In addition, the physical environment influenced the cognitive or physical workload necessary to obtain and use inhalers.

The locations of participants’ physician offices and pharmacies were generally accessible, especially for those with personal vehicles. Those dependent on rides from others, public transit, or medical transportation services occasionally encountered unreliable service, resulting in interruptions in inhaler supply.

“I had a doctor’s appointment. I had to be there by 7:30. Transportation didn’t come pick me up, so I was here. I also was supposed to go see the [pharmacy service]… Now I have to wait ’till Wednesday to get my medication.” (50F, Hispanic).

Participants’ inhaler affordability and treatment options were significantly impacted by their financial situation, having public versus private health insurance, their insurance benefits, and the drug formulary. If an inhaler was unaffordable, participants requested a more affordable inhaler, borrowed inhalers from others, or considered eliminating certain personal expenses.

Telephone or internet access facilitated contact with physicians or pharmacies via call or patient portal messaging. However, delays in refill approvals or out-of-stock inhalers at the pharmacy led some to run out of medication. Health care infrastructure supports, including automated refills and reminders, e-prescribing, and pharmacy mail delivery services, reduced the likelihood of running out of medication.

“My medicine is delivered. I receive it before it’s time for it [because] they just call me and tell me it’s bein’ shipped… and when they gonna be here.” (70F, Black)

Having extra inhalers was also helpful. Participants obtained extra inhalers by requesting refills early, multimonth pharmacy dispensations, and receiving inhaler samples.

Participants utilized their physical environment to integrate inhalers into their daily routine, ensure inhaler accessibility, and remind them to use or refill their inhaler. Access to inhalers was facilitated by strategic placement throughout the home or carrying inhalers in portable locations, though some found carrying inhalers around inconvenient.

“They’re right there on my bed stand, the ones I take in the morning, at night, my [tiotropium] and [fluticasone-salmeterol]. It’s just a ritual now with me. I wake up, go to the bathroom, come back, and I take my inhaler… I carry [albuterol] all the time in my purse… Even if I don’t need to use it while I’m out, I feel confident I have it and I don’t panic.” (68F, White)

Phone alarms, smart home devices, displays of their medication schedule or dose counts, and pharmacy prescription labels served as auditory or visual cues to use or refill inhalers.

“I've been visually impaired 4 years, so maybe 3 years ago she got [a smart home device] for my birthday… I used to set a reminder on her: Alexa, remind me to drop meds.” (50F, Hispanic)

Social Opportunity

Social opportunity refers to community or cultural influences that encourage or discourage inhaler use and support provided by family, friends, and professionals to manage COPD.

Exposure to other individuals with chronic respiratory disease, either in person or the media, facilitated and normalized inhaler use for several participants.

“It devastated me because everybody in my family— my mother, my father, and my grandparents, passed away due to respiratory failure… I’ve seen what they went through, and I take it very seriously. I’ve never missed a dose.” (52F, White)

While many felt comfortable using inhalers around others, others felt stigmatized using inhalers or having COPD.

“I don’t put it out there that I need my inhaler, because I know people who are like that. I think people pity you when they think that you are weak, and I’m not a weak person I don’t think.” (58M, Black)

Participants’ diverse relational experiences and social roles influenced adherence in several ways, including their trust in health care providers’ treatment recommendations and willingness to accept support in managing their COPD.

“When you go through a lot of things in your life… you don't know who to trust 'cause your family's supposed to be there to help you, protect you. When they're the ones hurting you the most, you're like, why is this [doctor] gonna help me?... I had trust issues. Now having to go to a stranger and have her tell me what’s wrong with me, it didn’t make sense to me.” (50F, Hispanic)

“I do not discuss any of my health issues with friends or family. I'm not comfortable with it, and I don't wanna burden nobody with whatever is goin' wrong with me… I should be able to handle it… I'm from the South, Mississippi, so we were brought up to be very independent. We don't rely on anyone.” (58M, Black)

While some welcomed help in the form of tangible or informational support, others lacked reliable support or preferred professional assistance.

“I'm the matriarch of my family, so now that I don't do a lot of the things that I used to do, I think people take it for granted… [They’re] just not willing or haven't accepted the fact that there's some things that I just need a little bit more help with today.” (73F, Black)

Physical Capability

Physical capability refers to the physical skills (e.g., coordination, dexterity, and sensory capabilities) needed to successfully operate or obtain an inhaler device. Given the qualitative nature of this study, we were unable to assess if participants possessed these physical skills. When asked about physical limitations to using inhalers, participants revealed that visual impairments made it difficult to locate their inhaler, distinguish inhaler characteristics (e.g., color), and read dose counters or medication instructions. Additionally, hand tremors and hyperventilating from dyspnea or anxiety affected proper inhaler technique. Limited mobility or illness impacted some participants’ ability to retrieve their inhalers or travel to their health care provider independently. Participants overcame physical disabilities or inadequate inhaler technique through support from health care professionals or loved ones.

“I would be hyperventilating. [My sister] said, “Breathe in.” She say, “Calm down. You won’t be able to get the medicine in your lungs.” So, I’ve learned… try to calm down before I use the inhaler.” (69F, Black)

Psychological Capability

Psychological capability refers to cognitive or mental processes involved in using or obtaining inhalers. These included having knowledge about the prescribed inhaler regimen, dosage schedule, and inhaler technique as well as executive functioning skills needed to plan, focus attention, adapt to changes, and weigh decisions.

Participants’ knowledge about their inhalers varied widely. Most could correctly name their inhalers, though some described them by their shape or color. Several participants reported using multiple controller inhalers of the same medication class or inhalers not actively prescribed. While most participants understood the difference between controller versus reliever inhalers and knew their correct dosage schedules, nearly half used their controller inhaler differently than prescribed—some knowingly, others unknowingly.

“[Fluticasone], albuterol, and [tiotropium]… [fluticasone] sometimes just one puff, period. [Tiotropium] 1 or 2 puffs. I mean, one capsule a day… Albuterol I use once a day. My [fluticasone] I use once in the morning, once in the evening… Sometime I just use both of ’em once. Two or 3 puffs. Two puffs albuterol, 3 puffs [fluticasone]… [Fluticasone], in case I have to use it, I use for emergency.” (69M, Black)

Participants’ description of their inhaler technique ranged from detailed to vague to incorrect.

“I first pick it up, or I shake it. Then I take a deep breath, clear my lungs, and then press the button, and it goes in. I hold it for 5 seconds, and then I take another deep breath, and do the same thing again.” (70F, White)

“By then I’m in a panic, so I’m using both inhalers in my mouth at the same time trying to breathe.” (69F, Black)

Verbal or written instructions from doctors, nurses, family members, pulmonary rehabilitation, smoking cessation class, and online sources facilitated proper technique for some participants. Others reported never receiving instruction or desired more instruction.

Cognitive processes like memory, attention, planning, monitoring, and decision-making were key to effective COPD self-management. Participants often forgot to use or carry their inhaler when rushed, distracted, depressed, stressed, or preoccupied with other responsibilities. Routines, reminders, and symptoms helped reduce forgetfulness, and some believed fewer devices or less frequent dosing would help. Planning was essential to maintain an adequate inhaler supply. Participants used dose counters, refill counts or reminders, and monthly refill routines to avoid running out of medication. Successful self-management required symptom awareness, monitoring, and informed decision-making about appropriate treatments. Barriers to these processes included comorbid conditions with overlapping symptoms, fluctuating symptom severity, varying inhaler effects, and inhaler misconceptions.

“[Albuterol] will be the first one I take because it’s my rescue medicine. If that’s not taking, then I’ll just try the [umeclidinium] more than the [fluticasone-vilanterol], ’cause the [umeclidinium]… it’s a little stronger than the [fluticasone-vilanterol]. I did learn the difference between the milligrams of the medication, so I can tell that would work faster along with the albuterol.” (63F, Black)

Reflective Motivation

Reflective motivation refers to conscious evaluations and intentions to use or not use inhalers. Participants’ intention to use their inhalers a certain way was informed by their beliefs about their capability to use inhalers, the consequences of using inhalers, the consequences of nonadherence, their goals for COPD treatment, and their personal identity.

Participants’ confidence in their ability to use inhalers varied from strong assurance to self-doubt. Symptom improvement, patient education, and experience managing chronic conditions facilitated participants’ self-efficacy. Barriers to self-efficacy included lack of inhaler education, having multiple inhalers introduced simultaneously, and experiencing side effects.

All participants believed that using inhalers was beneficial to them in some way, with benefits including symptom and functional improvement, feeling “normal,” preventing exacerbations, and avoiding anxiety. These beliefs were strongly reinforced by participants’ personal experiences of positive outcomes following inhaler use and largely aligned with their goals of treatment.

“I wanted to live for my grandchildren and for myself to be able to play with my grandchildren… I can breathe better playin’ with them.” (67F, Black)

Several beliefs about the need to use inhalers, the effectiveness of inhalers, and the consequences of nonadherence strongly promoted adherence. Those with high symptom burden, positive response to treatment, or previous exacerbations tended to believe inhalers were necessary every day. Some felt inhalers were most effective when used correctly and expected adverse consequences if used otherwise.

“If I don’t use ’em, I think that I’m going to have a downfall, and I’m not going to breathe… I’d probably find myself back in the hospital or even worse, intubated or on a ventilator.” (52F, White)

About one-third of participants knowingly used their controller inhalers differently than prescribed. These participants held contradictory beliefs about the benefits or effectiveness of inhalers. Many believed that they didn’t need or benefit from using inhalers as prescribed, especially if they weren’t experiencing bothersome symptoms every day.

“If I really don’t need the [budesonide-formoterol], I don’t use it twice a day. I’m not gonna waste it. ’Cause if I’m in the house, or even if I’m out, I don’t actually need the [budesonide-formoterol]. To me it’s an extra dose of something I don’t need.” (70F, White)

Others questioned the benefit or effectiveness of inhalers due to a lack of consistent symptom improvement, waning effectiveness over time, side effects, and ongoing exacerbations.

Many participants also believed that missing doses of their inhalers would be inconsequential. However, many agreed there would be adverse consequences if they discontinued inhalers altogether. Some did discontinue their inhalers to see how their body would react or to avoid perceived dependence or tolerance.

“At times, I don’t have to use my inhalers… when I can breathe better… [but] If I completely stopped using them? I know I have to use them because I have trouble sometimes breathing…. In some cases… I don’t feel like taking no medicine. I’m gonna tell how my body reacts. I’m just testing to see if things get worse, but usually they don’t.” (69M, Black)

Participants’ view of themselves was significantly affected by COPD. Many longed to feel “normal” and struggled to reconcile their identities as independent, capable, or healthy with their perception of someone with COPD. They feared becoming dependent on inhalers or being seen as sick, weak, or a burden. A few did not identify as having COPD at all.

“I’m just very independent, so it’s kinda hard for me to know that I’m gonna have to depend on a medication for the rest of my life to survive… But I need ’em, and I think that’s why I do not take ’em as prescribed. I take them as I feel like I need ’em.” (58M, Black)

“At the beginning, I wasn’t willing to grasp my COPD condition or any of my conditions because this wasn’t supposed to be how I saw myself… No, no, this ain’t me. I don’t got COPD… Being in denial for so long, it just had to get worse because I didn’t want to accept the help because I didn’t need it.” (50F, Hispanic)

“For me, I don’t have the COPD. I don’t know what or who’s saying that I got COPD. I don’t think that. You know, to me, I don’t have it.” (68M, Hispanic)

Automatic Motivation

Automatic motivation refers to the unconscious, instinctive, habitual, or emotionally driven motivations that impacted inhaler use. These included reinforcement (positive consequences that encourage a behavior), punishment (negative consequences that discourage a behavior), emotions, substance abuse, and habits/routines.

Symptom relief following inhaler use and symptom return following nonadherence (i.e., reinforcement and punishment, respectively) strongly promoted adherence and strengthened participants’ belief that inhalers were beneficial/effective, improved self-efficacy, restored their sense of normalcy, and mitigated anxiety about COPD symptoms.

“I could tell when I came down the steps that I forgot a medication… I can tell right away when I forget it… It’s very important that I take my medication.” (68F, White)

Variations in these reinforcing effects shaped participants’ preferences for certain inhalers.

“The emergency pump, my albuterol, it didn’t seem to try to help me with anything, but [budesonide-formoterol] would help me mostly. It helps me to breathe better, soothe me and open my congestion in my chest.” (64M, Black)

Negative consequences following inhaler use, including side effects or ongoing exacerbations, led some participants to discontinue their inhaler or alter their inhaler technique.

“The first one, they put me on I developed a really strong cough… I thought, maybe it was my mistake. I wasn’t doing it right… I didn’t wanna use it at all. I just felt like, "Is this hurting me more than helpin’ me?” (73F, White)

For others, a lack of reinforcement following inhaler use or lack of adverse consequences following nonadherence negatively influenced their beliefs and self-efficacy.

“Because I’m taking the medicine, I’m hoping that I feel better. So, mentally I do, 'cause I want it to work. I wanna get better. I think that it’s working, and I will continue to take it because I think that it’s helping. Physically, it’s not… I’m not getting better. As a matter of fact, if you ask me, I’m getting worse… I don’t think that it helps me because my lungs is so bad.” (66M, Black)

For many participants, strong emotions were associated with having COPD or using inhalers. While some felt relief or excitement to be prescribed inhalers, others felt disappointed they needed more medications. Many feared experiencing COPD symptoms and felt anxious when they didn’t use or possess their inhaler. Stress and depression contributed to both short- and long-term nonadherence.

“When I’m stressed, I just don’t take it… I don’t wanna be on all that medicine… I think part of my depression is because I have so much medicine that I do have to take.“ (63F, Black)

For most participants, incorporating inhalers into daily routines facilitated consistent use and reduced the mental effort of remembering to use them. Morning routines were the most consistent while afternoon and evening routines were less predictable. Participants often placed their inhalers in locations that were a part of that routine.

“They’re right there on my bed stand, the ones I take in the morning [and] at night. I wake up, go to the bathroom, come back, and I take my inhaler.” (68F, White)

Substance abuse interfered with inhaler adherence through low motivation for self-care. One participant who, “stopped pretty much doin' nothin' but getting high,” began using inhalers regularly after her physician referred her to an inpatient substance abuse program.

Discussion

Despite the prevalence and impact of COPD medication nonadherence, the patient experiences and perspectives driving nonadherence remain poorly understood. Using qualitative methods and the evidence-based COM-B behavioral model, we found barriers to inhaler adherence were common, varied by individual, and led to both short- and long-term nonadherence. While participants shared many strategies to overcome adherence barriers, nearly half were nonadherent to their controller inhalers as prescribed.

Our study fills important gaps in characterizing the pathways through which previously identified risk factors for nonadherence, such as disease severity,1 lead to nonadherence behavior. Although many of our findings align with barriers to adherence in other chronic diseases,10 our study revealed several novel findings unique to COPD or inhaler therapy that were not previously described in qualitative studies examining COPD medication nonadherence.17-20 We described specific physical disabilities that impair inhaler use in patients with COPD, a condition associated with high rates of comorbid disease.21 We also provided significant context and nuance to the various knowledge and skills barriers that lead to nonadherence, the effects of which may be cumulative considering the inherent complexity of inhaler regimens requiring controller and reliever therapies with different inhaler devices and dosage schedules. Notably, our study is the first to describe motivational barriers to inhaler adherence in COPD, including the perceived lack of need to use inhalers every day, belief that nonadherence is inconsequential, conflicts between patients’ personal identity and being ill with COPD, and the powerful reinforcing effects of bronchodilator medications.

Several participants reported using their controller inhalers incorrectly due to insufficient knowledge or skills. We considered these participants unintentionally nonadherent because they believed they used inhalers correctly. Intervention strategies within the COM-B model that address these barriers include education, skills training, or enablement (i.e., reducing barriers or increasing means).14 While several participants reported inhaler instruction was helpful, previous clinical trials emphasizing education and skills training have demonstrated modest effectiveness at improving adherence,22-31 suggesting instruction alone is insufficient to improve adherence. Furthermore, inhaler skills tend to deteriorate over time.32-33 Future strategies to address inhaler misuse may benefit from enablement approaches such as simplifying inhaler regimens, which observationally is associated with greater adherence,34 or designing devices that are easier to use.

Many participants deliberately used their controller inhalers differently than prescribed, reflecting intentional nonadherence driven by conflicting motivational factors. For these participants, their inhaler use patterns manifested their ambivalent beliefs that using inhalers benefitted them but also that inhalers weren’t always necessary, missing doses wouldn’t impact them, their desire to avoid dependency, or their self-image as a healthy person. We found significant interactions between the motivational factors, most often involving reinforcement/punishment, resulting in feedback loops that strengthened or weakened adherence. Interestingly, among the COM-B intervention functions suitable to address motivational barriers, creating an expectation of a reward or punishment is effective for addressing both reflective and automatic motivations.14 Given the powerful influence of reinforcement in our study, future interventions to improve adherence may benefit from leveraging rapid-onset bronchodilators with more immediate effects on symptoms that reinforce use. One potential strategy to increase utilization of controller therapies is to develop combination inhalers that contain a rapid-onset short-acting bronchodilator and a slower onset long-acting bronchodilator (e.g., albuterol-tiotropium). This combining of rapid-onset bronchodilators with other less reinforcing inhaled therapies is a strategy proven effective in the management of asthma.35-38 Another potential strategy is to use long-acting bronchodilators with rapid-onset (e.g., glycopyrrolate-formoterol) as needed for symptom relief. Other intervention strategies, such as persuasion through motivational interviewing, may require tailoring to the context of each patient since the interplay of motivational factors may be highly individualized.

Most participants in our study experienced short-term lapses in inhaler use due to opportunity or capability barriers, consistent with findings from O’Toole et al.17 Although many of these barriers are well-known and common to other chronic conditions, like medication unaffordability, others may be less obvious to clinicians and more specific to treating patients with COPD or inhaler therapy. For example, patients with COPD may be at higher risk for physical capability barriers compared to patients with asthma due to older age and a higher burden of comorbid diseases that impact their visual acuity, dexterity, or mobility.21 Similarly, psychological capability barriers like forgetfulness may have a greater impact on adherence to multiple inhaler devices with different dosage schedules than it would on adherence to a once daily statin used to treat hyperlipidemia. The potential impact of interventions targeting such opportunity or capability barriers remains unclear, as many participants were adept at overcoming these obstacles independently or with social support. Nonetheless, our findings bring awareness to clinicians about the breadth of adherence barriers faced by patients with COPD and highlights the importance of routinely screening for barriers and providing assistance as needed.

There were several strengths and weaknesses of our study. Using qualitative methods and an evidence-based behavioral model allowed us to comprehensively explore the perspectives and experiences driving adherence that are difficult to measure quantitatively. Giving voice to an understudied population of racial/ethnic minorities with limited income is a further strength, although results may be impacted by single site recruitment. Generating rich, contextualized qualitative data from predominantly minority and low-income adults with COPD comes at the expense of generalizability, which is not an aim of qualitative research. Although reflexivity was practiced throughout the study, the investigator conducting the interviews and analysis (SL) was a physician so there is a potential for investigator bias.

Conclusion

Barriers to medication adherence among predominantly minority and low SES individuals with COPD were common and varied by individual. Knowledge and skills barriers may be well-suited for interventions that utilize education, skills training, or enablement, whereas motivational barriers may be best addressed through utilizing pharmacotherapy with more immediate effects on symptoms or motivational interviewing at the individual level.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: SLL, EMO, AVP, MJJ, VGP, and LKS were responsible for the conception/design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the work and reviewing it critically for important intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

Disclosure of use of AI tool: ChatGPT was used for editing the manuscript. Sections of prewritten original text were added to ChatGPT, and it was prompted to provide a more concise version of the text. The ChatGPT output was reviewed, and some suggestions were incorporated into the manuscript in the form of word substitutions or deletions.

Declaration of Interest

SLL reports support for this manuscript from grants (American Thoracic Society/American Lung Association/CHEST Foundation Respiratory Health Equity Award, National Institutes of Health [NIH] KL2TR002002, and NIH UL1TR002003). MJJ reports support for travel to scientific meetings from grants (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute). VGP reports support for unrelated studies from grants (NIH R01, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R01, NIH K24), royalties from UpToDate, consulting fees from Humana, participation on a data safety and monitoring board (NIH R01), and a leadership role as the Assembly Chair for the American Thoracic Society Behavioral Science and Health Services Research Assembly. LKS reports support for unrelated studies from grants (NIH) and honoraria for serving on an NIH grant review panel. EMO and AVP have nothing to declare.