Running Head: Home-Based Palliative Care: COPD Patient Perspective

Funding: This research was funded by the University of Colorado Doris Kemp Scholarship program.

Date of Acceptance: May 6, 2020

Abbreviations: home-based palliative care, HBPC; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; health-related quality of live, HrQOL; palliative care, PC

Citation: Hyden KF, Coats HL, Meek PM. Home-based palliative care: perspectives of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and their caregivers. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2020; 7(4): 327-335. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.7.4.2020.0144

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (56KB)

Introduction

Adults with advanced stages of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) typically experience increased episodes of dyspnea, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and anorexia as their disease process progresses.1,2 The increase in symptom burden also often leads to more frequent exacerbations that are defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease as “usually associated with increased airway inflammation, increased mucus production and marked gas trapping.”3 When there is a lack of supportive services in place for patients with COPD after a hospitalization for an exacerbation, there are unaddressed care needs resulting in uncontrolled symptoms for adults with severe COPD. This lack of supportive care is associated with frequent rehospitalizations and increased health care utilization, as well as dissatisfaction with care, and decreased health related quality of life (HrQOL)4,5,6 Existing literature describes home-based palliative care (HBPC) as a supportive service that can help address the care needs, increase satisfaction with care, reduce rehospitalizations, and thus increase the patients’ HrQOL.6-9

HBPC clinicians are skilled in symptom management as well as management of complex psychosocial symptoms related to depression, anxiety, and distress.10 HBPC clinicians also collaborate with other service providers in the care of patients with COPD. For instance, pulmonary rehabilitation is a well-known important component of integrated care for patients with COPD, however, it is usually offered in the hospital out-patient setting and many patients do not utilize this service. This is largely because they do not understand the benefits that the pulmonary rehabilitation interventions—exercise training, self-management education, and nutritional education—can have on their symptoms and HrQOL. HBPC clinicians can educate the patients about the importance of such interventions, and help coordinate the care service as part of the patient’s holistic care plan.11

Palliative care (PC) had its inception in the 1960s, and since then has evolved into being used in various care delivery models including: inpatient hospital settings, outpatient clinics, and community-based, which can include homes, skilled nursing facilities and assisted living facilities. PC, unlike hospice care which is appropriate when a patient has a prognosis of six months or less and no longer desires to pursue life prolonging treatments, is available to patients at any stage in the serious illness trajectory.12 The World Health Organization in 2017 defined PC as, “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.”13

Despite the many benefits of PC, it is estimated that only about 20% of COPD patients receive referrals to any form of PC during the late phases of their illness.14 Moderate to advanced stages of COPD are associated with increased health care demands and costs due to increasing symptoms, care-seeking and hospitalizations.11,14 It is at this point that HBPC (also sometimes referred to as “community-based palliative care”) becomes a vital aspect of care for the patients and their caregivers as it allows for the provision of advanced symptom management, advanced care planning and goals of care conversations in a setting in which patients and their caregivers are comfortable.15

HBPC offers meaningful benefits to patients, families, and care providers. It also decreases hospitalizations and health care costs but, like all forms of PC, is underutilized in patients with COPD. This is unfortunate since patients with advanced COPD, and their family caregivers feel that palliative care is acceptable and should be integrated into care before end-of life. Therefore, while HBPC is viewed as a positive, additive layer of support to patients with COPD and their caregivers, questions remain as to which aspects of HBPC the patients with COPD and their caregivers perceive as the most meaningful. Identifying these aspects of care could decrease confusion about, and increase satisfaction with, the HBPC offered. This could potentially result in increased referrals to HBPC by providers, as well as increased utilization by patients with COPD and their caregivers.

Although HBPC for patients with serious illness has been documented to improve symptom management and quality of life, it is not clear how this is true from the perspectives of patients with COPD and their caregivers, specifically. Understanding their experiences, in the context of the 8 domains of quality PC, as identified by the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum in PC,16 may provide information that will help develop standardization of best practices for HBPC in individuals with COPD post-acute events such as an exacerbation. The purpose of this study is to describe which domains of HBPC are used and considered meaningful from the perspectives of patients with COPD and their caregivers.

Methods

Design

A descriptive design with narrative analysis methodology was used. The primary aim of the study was to describe the domains of HBPC that were part of the HBPC intervention and considered meaningful from the perspectives of patients with COPD and their caregivers in the 30 days post hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation. A secondary aim was to determine the similarities and differences in the components of HBPC considered meaningful between the patients with COPD and their caregivers post an exacerbation of COPD.

Recruitment Procedures

Participant dyads of patients and their main caregivers were identified by the community hospital’s inpatient palliative care team prior to hospital discharge. Potential participants confirming interest in participating in the study were referred to the research team. There was a total of 15 dyads referred: 2 dyads failed the initial chart review for inclusion criteria; 2 dyads refused HBPC, and the patient in 1 dyad died before receiving HBPC, resulting in 10 participating dyads. Informed consents were obtained from the interested and appropriate participants in compliance with human subjects’ protection guidelines. The local community hospital, the HBPC program, and the academic institution’s institutional review boards, all approved this study. Once the signed, informed consents were obtained, home visits to conduct the interviews were scheduled at 30 days post hospitalization, after receiving HBPC provided by 1 of 2 nurse practitioners in the local HBPC program.

Data Collection

The first author met with the patient and the main caregiver in the patient’s home and conducted the interviews using an interview guide developed from the 8 National Consensus Project’s domains for Quality PC.16 (Appendix A in the online supplement). The audio-recorded interviews were collected by the first author. Each interview was transcribed verbatim by the first author. The audio-files, transcriptions and demographic patient information were stored on the first author’s encrypted computer system.

Data Analysis

A thematic analysis was performed by the first and second authors. An inductive emic approach to coding was used.17,18 This approach allows codes to form patterns as they emerge from the transcripts as well as to see the recurrent patterns of experiences of HBPC for patients with COPD and their caregivers. Each of the 2 authors independently coded the first 3 transcripts using the participants’ actual words. Once the initial codes were chosen by consensus between both authors, all transcripts were read again through a recursive process for creating any additional codes until no new codes emerged.17,18 Then the codes were compared across each transcript to find similarities and differences. This comparison process was completed using a matrix in Microsoft excel of all codes categorized by patient/caregiver.19

Results

The COPD patients’ ages ranged from 56-88 years, and the caregivers ranged from 42-75 years. There were 5 male and 5 female patients and 4 male and 6 female caregivers. Caregivers consisted of spouses, partners, and adult children of the patients. The interviews took place in 3 counties in Tennessee and 80% were conducted in the home. Two interviews of patients and caregivers were conducted in institutions because 1 patient was re-hospitalized at 30-days and 1 resided in a skilled nursing facility.

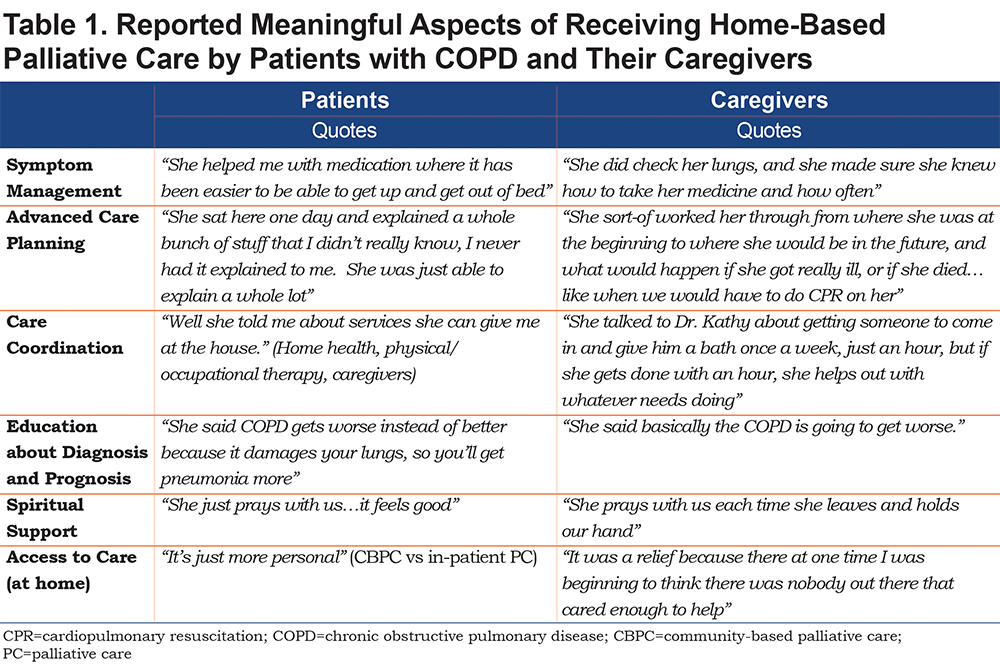

The 2 main themes that emerged were: meaningful aspects of receiving HBPC from the perspectives of the patients and caregivers and potential areas for improvement in the HBPC service provided from the perspectives of the patients and caregivers (Table 1). To further describe these themes, the findings will be discussed using the framework of the National Consensus Project’s domains for Quality PC.16

Theme 1: Meaningful Aspects of Receiving Home-Based Palliative Care from the Perspectives of the Patients and Caregivers

In the HBPC provided, the domains—psychological and psychiatric aspects of care, social aspects of care, and spiritual, religious and existential aspects of care—tended to overlap. This overlap relates to the many ways patients and their caregivers cope with serious illness. Based on the results of the interviews in this study, patients and caregivers reported spiritual and emotional support as meaningful aspects of the care they received in the 30-days post hospitalization HBPC intervention. This is important as these aspects of care impact the quality of life of the patients and their caregivers. Improving quality of life for this population is a goal of providing quality PC.16,20

Three of the domains—cultural aspects of care, care of the imminently dying, and ethical and legal aspects of care—all pertain to the part of HBPC that is referred to as advanced care planning and discussions regarding goals of care. In addition, HBPC providers explore the cultural preferences and concerns of patients with COPD and their caregivers, as well as provide education about the diagnosis and prognosis. Both are complementary in developing an advanced care plan based on goals of care that aligns with the cultural preferences of the patients and caregivers.16,21 According to the results of this study, patients with COPD and their caregivers identified that the HBPC intervention provided meaningful education about the diagnosis and prognosis, as well as discussions about goals of care and advanced care planning. A large part of ethical and legal aspects of care in PC is having goals of care and/or advanced care planning conversations discussing such things as code status and what they would and would not want done for their care in an emergency situation. Three patients and 1 caregiver reported that discussing code status occurred only in their HBPC encounter.

Ultimately, the aspects of care that were perceived and reported as meaningful among the patients and the caregivers, from most to least reported, were spiritual support, education about diagnosis and prognosis, access to care at home, advanced care planning, care coordination, and symptom management. There were only slight differences in the frequencies of the reported meaningful aspects of care between the patients and caregivers, with caregivers reporting higher on having access to care at home (5 versus 4) and advanced care planning (5 versus 4); and the patients reporting care coordination (5 versus 3) as meaningful more often than the caregivers. (Table 1)

Theme 2: Potential Areas for Improvement in the Home-based Palliative Care Service Provided from the Perspectives of the Patients and Caregivers

In the domain of structure and process of care, the results of the study reveal that 9 out of the 10 patients received only 1 HBPC provider visit within 30 days post hospitalization, which is not the best process for care. This limited access to a HBPC provider in the critical 30 days post hospitalization for an exacerbation could contribute to rehospitalizations.5 For instance, 1 out of 10 patients in the study was rehospitalized for an exacerbation in the 30-days and reported, along with the caregiver, that symptom management was a potential area of improvement. The patient stated, “She just said to use my prednisone, but it don’t help my breathing,” The caregiver said the patient“hasn’t (improved) in breathing, he still gets fatigued and out of breath. He can’t walk.”The other potential area of improvement that was reported by one caregiver was advanced care planning. The caregiver stated, “He doesn’t have a Living Will, no decisions changed [after the HBPC intervention].”

Discussion

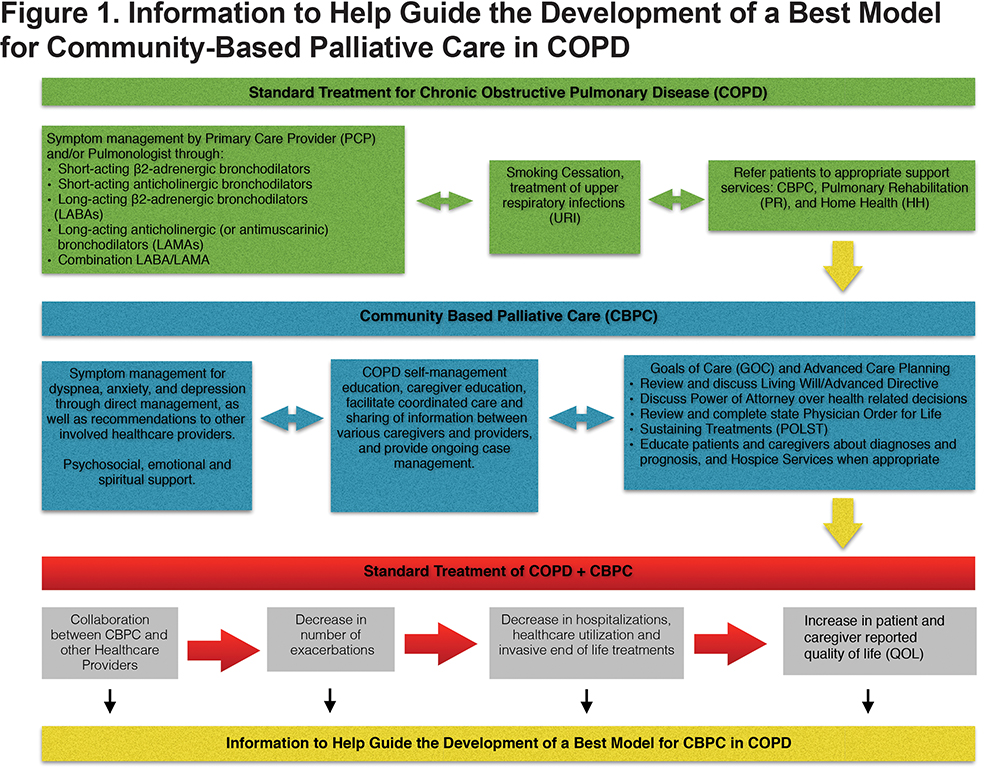

The patients and their caregivers in this study reported both meaningful aspects as well as potential areas for improvement in their experiences with HBPC. The meaningful aspects of their experiences with HBPC highlight the value that the care service adds to standard treatment (green in Figure 1) combining symptom management and self-management to provide the best model of care for individuals with COPD. HBPC added an extra layer of support that the participants, patients and caregivers saw as a meaningful addition to the care team. There were 2 potential areas for improvement: advanced care planning and symptom management. However, advanced care planning may not have been successful depending on the other circumstances related to the HBPC visits such as: clinician’s time, lack of patient/caregiver participation, or distraction, or even the clinician determining it was not the right time to have the conversation. Advanced care planning is an ongoing conversation and can be sensitive in nature. Most participants (9 out of 10) received only 1 HBPC visit in the 30 days post hospitalization. One visit limits the potential interactions that would allow for such ongoing conversations. However, a study done on early, integrated palliative home care for patients with COPD determined that a cadence of monthly visits was appropriate as long as the patient was stable.9

It is noteworthy that only 2 patients and 3 caregivers remembered meeting with the inpatient PC team and being educated about HBPC. Though a hospitalization is a time of high stress, and includes interactions with multiple providers, this finding highlights an area for possible improvement where an interprofessional collaborative team of clinicians (medicine, nursing, social work, and spiritual care) across settings could focus more time on patient and caregiver education and understanding of care services available. Doing so could help streamline the continuity of care and improve uptake of such services for the patients and caregivers.

PC, including HBPC, has been shown to decrease the use of acute care health services in the last year of life for patients with many serious illnesses, including COPD,22 and increase access to hospice care services when appropriate.23 Decreasing the use of acute health care services by COPD patients is important because, as part of the Affordable Care Act, there are penalties for the hospitals when there are excess hospital readmissions.24 Yet, despite the efforts to enact hospital readmission prevention programs in the COPD population, there has been little improvement in rates of rehospitalization. The incorporation of HBPC in this study did provide opportunities for more education about the COPD diagnosis and prognosis, as well as advanced care planning discussions with patients and caregivers about their preferences on patient-caregiver-centered goals of care. Though the implication is that the incorporation of these PC interventions may result in decreased hospitalizations, the reality is that there is no significant published data to back this up.9

Current literature explores HBPC from the perspectives of the stakeholders in HBPC, as well as the perspectives of HBPC providers and administrators, this study has added depth and breadth from the patients and their caregivers to the knowledge we have about HBPC. Specifically, this study informs what we know about how HBPC can impact the experiences of patients with COPD and their caregivers within the first 30 days post hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation.23 The results of this study showed education and spiritual/emotional support as the most meaningful aspects of HBPC, which aligns with the findings of another study that showed illness understanding (education) and coping with COPD and emotional symptoms are palliative care needs for patients and their caregivers.5 Furthermore, this study aligns with desire of the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Nursing Research to improve palliative care science25 in the following key areas: 1) caregiving issues, 2) effective palliative interventions, 3) improving clinician-patient discussions about preference for life sustaining treatments, and 4) developing the best model for HBPC. Given the results of this study, future research should further explore the perception of HBPC based on the experiences of patients with COPD and their caregivers by using a larger population size, a longitudinal study design, and including participants receiving care from various organizations and providers.

This study has several limitations: the small sample size, use of only 1 HBPC program consisting of 2 nurse practitioners delivering the HBPC, participants were mostly white, and 90% of participants received only 1 HBPC visit within the 30 days post hospitalization. Additionally, there were no significant differences between the perspectives of the patients with COPD and their caregivers, and this may be due to the fact that for most of the interviews, the patient and caregiver were in the room together.

Conclusion

The outcomes of this study provide information that describes the aspects of HBPC that patients and their caregivers found most meaningful, as well as potential areas for improvement. An understanding of the most meaningful aspects of HBPC from the perspective of the patient with COPD and their caregivers can be used to inform the development of the best model for HBPC for this patient population, as well as potentially increase uptake of, and access to HBPC for patients with COPD and their caregivers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the local hospital, Maury Regional Medical Center, as well as their inpatient palliative care team for their support and help in participant recruitment. Also, a special thanks to Compassus and their palliative care team.

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study. Dr. Hyden acquired the data, and along with Dr. Coats, performed data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed substantially to the writing and revisions of the manuscript, contributed to the intellectual content of the article, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Declaration of Interest Statement

KFH is employed as an HBPC nurse practitioner for the HBPC program used in the study. She did not deliver or control the care provided to the study participants. All interviews were conducted by KFH, and no information was shared with the HBPC nurse practitioners delivering the care. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.